Matters of the Sea / Cosas del mar and the Gulf between Homes

In the preface to Richard Blanco’s Matters of the Sea / Cosas del mar (2015), he writes that his writing has long focused on “what it means to be American as much as what it means to be Cuban,” while remaining committed to “honoring and documenting the lives, sorrows, triumphs, and losses of my parents and grandparents and the exile community that raised me.” Blanco does all this in his long poem about “America,” about Cuba, about the sea—the sea that connects Cuba to the United States, spanning those ninety miles between Cuba and Key West; the sea that acts as a barrier between the two countries whose governments don’t talk.

“The sea doesn’t matter, what matters is this: / we all belong to the sea between us,” Richard Blanco writes. Growing up Cuban American in Miami, the sea was important to me too. My family went to the beach together whenever we could, it being a rare place we could relax. I have so many memories of Abuela sitting on the sand, smiling, mimicking the smile she made in pictures at Varadero Beach with her family when she was a child. I think of taking walks with my sister and mother, picking out shells and marveling at sand dollars lightly buried under the sand in the sea. I think of Pops teaching me how to body surf, think of him playing catch with me in the rain. I think of how Abuelo would almost always be the last one out in the water, floating farther out than anyone else, and of how I’d swim in front of him; he’d look at me, look up at the sky, then look back down to the sea, humming a song I’d never learn the name of but would hear repeatedly for the rest of my life. Going to the beach with a family of Cuban exiles, you can’t not hear about the island they used to call home, so as the bright Miami days turned into the amber sunset glows, I’d hear more and more about the island.

Blanco wrote Matters of the Sea / Cosas del mar after former President Barack Obama announced the “normalizing” of relations between the United States and Cuba. Blanco read it at the reopening of the United States embassy in Havana, which is on the road right off El Malecon. Blanco wrote it (and had it translated into Spanish by Ruth Behar) in order to mark the occasion, and he wanted people on both sides of the sea to be able to read it. I bought the book when it was published shortly thereafter, and took it with me to Cuba, reading it on both sides of the sea—on El Malecon and on the levee in front of my house.

In the book’s preface, Blanco includes the questions he worries about when writing, when thinking about Cuba: “Was I Cuban enough for a new Cuba? Would I be too Cuban for America? Would the stories of my exile family and community be is counted? Could I be faithful to the people of two countries and cultures I adored?” Those are questions that are not unfamiliar to any “hyphenated” American. Not unfamiliar to any of us who are a product of exile, who have inherited the trauma of their families having lost their home. Every time I go to Cuba, I am faced with my own questions. Will going here hurt my father, my family? Will coming here tear open a wound, one I’ve inherited, but that lives deeper into the skin of the people I love? Will I waste my time, and not do everything I should be doing, for me and mine? And every time I go to Cuba, I spend the first moments after I’m settled walking over to El Malecon and sitting by the sea. I take a moment to let the pains wash away in the waters, in front of the place that mis abuelos and Pops, and now me and my sister, have all sat by. I’m not with them physically, like on our beach days when I was a child, but I am with them mentally, emotionally, spiritually, nonetheless.

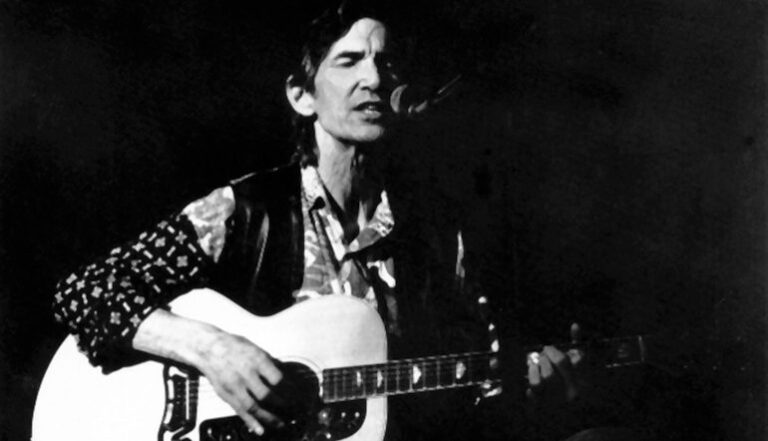

The epigraph for Matters of the Sea / Cosas del mar quotes from José Martí’s “the Poet Walt Whitman”: “Everything that lives loves him: the earth, the night, the sea love him.” The first time I went to Cuba, I sat on El Malecon with someone dear to me. I stared into the sunset until it went dark, a band playing music next to us, passing around guitars, making percussion instruments out of things that weren’t percussion instruments minutes before. I remember not knowing if the songs were covers or originals, but I could nod along with the band, quietly keeping the beat, listening and participating and living in that moment. The singer raised his hands to the sky, then to the sea, as if it were all his. I remember thinking how that moment seemed to capture all of the magic of my family’s stories, of El Malecon, of Cuba, but in the present tense—how that magic seemingly still lived here. My beach days of Miami were being mirrored on the other side of the sea.

“All of us / once and still the same child who marvels over / starfish, listens to hollow shells, sculpts dreams / into impossible castles,” Blanco writes. So much of Cuba is tourism, museo del mundo—them trying to cosplay a bit of an old era, with all the nationalism and communism thrown in, everyone happy, no food or fish or medical supply shortages, no apagones, no full jails. I think of how on the other side of the sea, Miami does the same, neighborhoods and businesses cosplaying an old Cuba, as if 1958 was a good year there, all the good guys and bad guys trading positions, no more human or real. Both sides sell a hustle that only further disappears the actual people. I think of these lines while sitting on El Malecon, thinking of one of Pop’s “impossible dreams”: riding in a Cadillac on El Malecon—something that never happened in the real world, him being a child exile before that dream was ever possible. He rode with his father, Pompilio, who was young, strong, not eaten from the inside out like a hollow shell from his exile. They talked and maybe they said goodbye, Pompilio never seeing Cuba in this world again—and maybe that’ll be true for Pops too.

Blanco writes of “planting maple or mango trees / that outlived them; our grandmothers counting / years while dusting photos of their weddings— / brittle family faces still alive on our dressers now.” Sitting on El Malecon and I think about all the photos I’ve seen of Cuba, of the protests on July 11 of last year, of the fire in the factory in Matanzas that added to the apagones and energy issues in Cuba, of the artists who keep getting beaten and arrested for their protests, for their art. I think of the personal photos and sights I’ve seen—the photos of my father’s house, with mold on the walls; the photos of mi abuela’s old house, which looked good to me, let me dream of what their life must have been like, but which she thought looked terrible, merely a house gutted of her family that made it a home. When I visited Cuba I met cousins I’d never met before, that I didn’t know existed before; they went from ghosts to names on a phone to people I could hug and eat pizza with and share coffee and rum with. The people in the dresser of my mind have slowly been coming to life.

“My cousins and I now scouting the same stars / above skyscrapers or palms, waiting for time / to stop and begin again when rain falls, washes / its way through river or street, back to the sea,” Blanco writes, and I think of how many families have been split up, by dictators and empires, both using the people and their families as pawns. I think of how many people are split between the sea. I think of how my family shares so many of those scars and wounds through separation. How we don’t know who is buried where in one country, how we at times haven’t known who lived where, how decades have passed without us hearing from one another.

I think of all this, scribbling lines into my notebook while sitting on El Malecon. I think of all this reading Matters of the Sea / Cosas del mar in the comfort of my New Orleans home. I reread the last lines—“Listen / again to the echo—the sea still telling us the end / to our doubts and fears is to gaze into the lucid blues / of our shared horizon, breathe together, heal together”—and I just hope that what I write can help gringos understand, and I hope what I write can help Cuban exiles feel a little sense of home. I hope that I can go to the beach with my family soon, and that abuela can think about the photos of the beach and her home in Cuba, that my sister and mother can think of my sister’s trips, and our stories from Cuba, as they collect shells on a walk in Miami, that Abuelo can maybe catch himself humming a song I sing to him from Cuba the next time we float deep into the water, staying longer than everyone else. On one of my last nights in Cuba, on a clear night in a small town outside of Havana, I look up and can see so many stars. Pops can’t see them in the Miami night, blocked by a cone of light pollution, but I take comfort in knowing, at that moment, that he must have been looking up at the same time, and even in the black sky, maybe he can see a little more of his ghosts, a little more of his loves, a little more of his home, from the stories I can tell him from the other side of the sea.