Memory and Metaphor in Mai Der Vang’s Afterland

Many of us who love poetry think of metaphor as being somewhere in its DNA. Without metaphors, somehow, it seems, poetry would not be itself. Even when a poem contains no metaphors on the line level, it usually contains juxtaposition of different ideas, different contexts, associational leaps that enact metaphor by putting Thing A against Thing B, using one to help illuminate the other, to make sparks.

My understanding of metaphor was shaped by an essay I read long ago by poet and novelist Stephen Dobyns called “Metaphor and the Authenticating Act of Memory.” In this essay, Dobyns writes that one of the ways that a poem makes a relationship with a reader—invites, really, the reader to participate in the poem’s own making—is through “the authenticating act of memory.” In other words, Dobyns says: “[T]he reader must be able to recognize and respond to the world of the poem, either through imagination or personal experience.” Part of what makes metaphor so pleasurable is that shock of recognition, when the two parts of the metaphor, the two things being compared to each other, click into place. This happens on the unconscious level, or the level of memory, before it happens consciously: “I understand before I know why I understand. The effect is to surprise me with myself.”

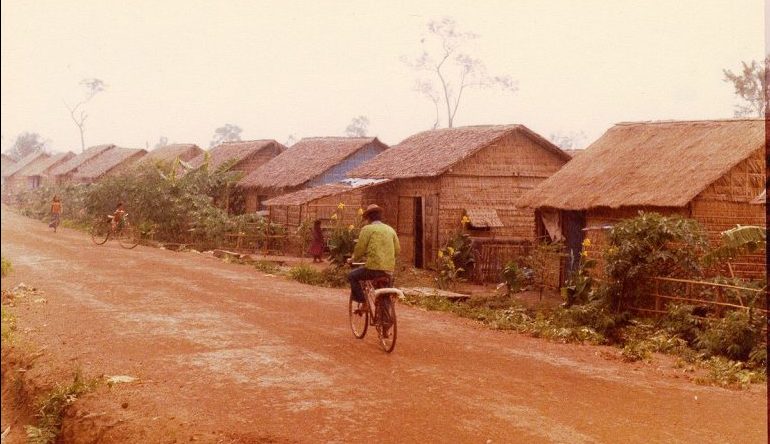

This essay was very much on my mind when I read Mai Der Vang’s Afterland, one of the most metaphor-dense collections I’ve encountered. Vang’s family fled Laos at the end of the Secret War there, so-called because the American government carried out confidential operations there, arming Hmong fighters the occupying North Vietnamese.” When Laos fell, the American government dropped everything and evacuated their troops, leaving the Hmong with nothing, and Laos devastated by years of conflict. Hmong people were resettled, usually after spending time in refugee camps. Vang’s family wound up in Fresno, California; Vang was born the year they finally arrived there. In a piece for the New York Times, Vang writes:

I’ve wondered: How does one memorialize a failed war that most people don’t even know about or would rather forget? How will my generation attempt to retain the memories of that war so that future generations will know? … Even now, I ask more questions than I have answers. But I do know that many of us are innately tied to this trauma as if it were strung into our DNA.

For the Hmong, to retain history and identity means also to retain trauma and loss. I carry the afflictions of this war even though I have never heard a bomb explode or feared my footsteps might trigger a mine. This war is my inheritance.

In Afterland, then, Vang is bringing to life a trauma that she did not directly experience. I began to wonder: if Dobyns’s ideas about the metaphor are correct, then Vang’s work is twofold. Through the metaphorical work of the poems, she at once seeks to imaginatively understand the war, and she must also spark the same understanding in the reader. Although Vang has these experiences, as she puts it, in her DNA, the central work, the “authenticating act of memory,” is the same for both reader and poet.

It’s fitting, then, that the first line of the book is a metaphor. In “Another Heaven,” Vang begins, “I am but atoms / of old passengers // Bereaved to my cloistered bones.” But rather than repeat the idea that Vang explored in her piece for the Times, about war being in her DNA, she explores the notion as a metaphor. Her genetic ancestry is not merely a biological inheritance—it is a collection of “passengers,” a word meant to alert us of flight, travel, resettlement, and of the current journey these “kin” take inside of Vang. For me, though, it’s that third line that most clearly performs that act of surprising unconscious recognition that Dobyns describes: the atoms are described as being “bereaved to” the speaker’s “cloistered bones.” We understand bereavement as having suffered a death of a loved one, but the unusual use of the word “to” may bring us up short. “Bereaved to” makes memorable use of an archaic use of the term, in which bereavement meant to remove by force. It’s partly Vang’s use of “cloistered” to describe the bones on which the passengers travel that helps us recognize the unusual way bereavement is being used. The association of a cloister chimes with other occasions in the book where Vang makes use of Western religious iconography in her metaphors, which live next to the Hmong spirits which haunt the text—a nod perhaps to the missionaries in Laos, whom Vang writes about in poems like “Original Bones.”

But most of all, this opening shows the first utterance of one that Vang makes a version of over and over in the text. I carry something within me, the speakers insist. I am both myself and more than myself. The poem “Progeny,” for example, puts it this: “Home is container is memorial.” Container, cloister, vessel, “a dusty gallery,” “an iron jar.” All of these are metaphors for the body in Vang’s vision.

In Dobyns’s essay, he writes that the recognition of metaphor is “almost like a vision, an exterior voice” that has the “peculiar side effect of momentarily taking us out of our isolation and joining us to some larger idea of the world.” We can imagine the act of metaphor doing this with each poem that Vang wrote, collapsing the distance between Vang and her ancestors. And, of course, as readers, we can feel it happening for us, through the precision and originality of Vang’s work.