Meridel LeSueur and the Golden Age of Proletarian Writers

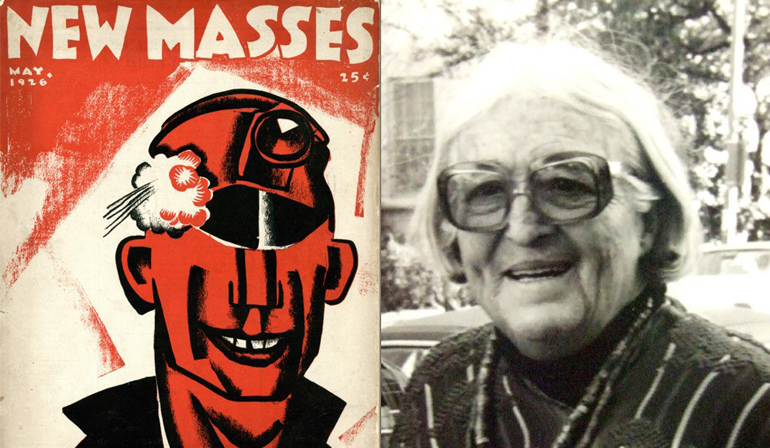

Born in 1900 and raised by Midwestern socialists and farm activists, author Meridel LeSueur had a radical pedigree. In her twenties, she lived in a New York anarchist commune with Emma Goldman. Her earliest writings addressed left causes like migrant workers’ rights and Native American autonomy. By 1925, she had become an official member of the Communist Party USA.

LeSueur’s novel The Girl tells the story of an unnamed protagonist who flees the poverty and abuse of her childhood to find a job at a restaurant/speakeasy in Depression-era St. Paul, Minnesota. Originally written in 1939, the manuscript was blacklisted during the McCarthy era until renewed interest from the second-wave feminist movement led to its eventual publication in 1978.

The Girl is a social bildungsroman. The protagonist’s understanding of herself and the world develops through her interactions with other working women: Clara, a plucky young prostitute; Belle, the restaurant owner, who excuses her husband’s abusive behavior because of the pressures of their poor material conditions; and Amelia, a member of the Workers Alliance, a political organization that attempted to mobilize unemployed workers and unite the various causes of the American left in the 1930s.

These women are the girl’s saviors, providing her with the emotional and physical resources to survive the brutality of the men around her. She falls in love with Butch, a frequently violent and chronically unemployed restaurant patron, and becomes pregnant. Desperate for money to support her child, the girl assists Butch in an ill-fated bank robbery that results in his death. The last half of the brief novel devolves into a portrait of misery and brutality. The girl is sent to a maternity home where she discovers she will be sterilized after she delivers. She escapes with the assistance of Amelia then discovers that Clara has undergone forced electric shock therapy and is near madness and death. And yet, The Girl ends with a tentative suggestion of hope: a memorial for Clara turns into a demonstration against the conditions that caused her death and the girl names her newborn daughter after her departed friend.

LeSueur’s background made her one of the many self-consciously working-class writers whose narratives would come to be known as proletarian literature, a body of fiction and essays published throughout the 1920s and 1930s by writers like Agnes Smedley, Jack Conroy, Mike Gold, and Tillie Olsen who came from working class backgrounds and wrote social realist stories for working-class people. Like many of these writers, LeSueur originally published excerpts of The Girl in the New Masses, one of the many “little magazines,” or small literary and political journals established during the height of modernism.

Despite the large body of proletarian narratives produced during this period, few novels like The Girl survived the Cold War, and those that did are considered more of a historical document than literary art. This is due in large part to the cultural Cold War, partially enacted in the pages of little magazines similar to the New Masses.

Of the sixteen essays contained in Lionel Trilling’s touchstone of mid-century literary criticism, The Liberal Imagination, five were originally published in the Partisan Review, a little magazine that sprung out of the communist-affiliated John Reed Club. However, by the 1940s, when Trilling was publishing those essays, the journal had become extremely critical of communism (more specifically Stalinism), and Trilling’s literary criticism became a direct indictment of communist-affiliated, social realist writers who had captured readers and critics in the early half of the twentieth century.

It’s not hyperbolic to claim that The Liberal Imagination changed the course of American literary criticism, and as a result, American literature. The most enduring essay, “Reality in America,” argues that Henry James, not Theodore Dreiser, is the great American realist writer, an opinion now taken for granted in most literary and critical circles. The Dreiser-James argument exemplifies the project of The Liberal Imagination: American literature must rescue itself from the expressly ideological social realism (Dreiser, a communist) by focusing on the subtleties and contradictions of a character’s consciousness (James, a member of the intellectual bourgeoisie). But the other project of The Liberal Imagination was inherently political and moralistic: to champion bourgeois individualism and detach realism from its social and working-class constructs, as established by proletarian writers like LeSueur.

With broad strokes, Trilling denounces the communist party and its writers for having “succeeded in rationalizing intellectual limitation” and “in twenty years, produced not a single work of distinction or even high respectability.” The Partisan Review, nearly bankrupt by the 1950s, was rescued by covert funding from the CIA, and the legacy of Trilling’s essays have made books like The Girl difficult for our twenty-first century readerly sensibilities. Though the first-person protagonist narrates the story, her perceptions and voice disappear for large chunks of the novel. But this is not coincidental, nor is the fact that the girl has no name; she is meant to universalize a set of conditions and experiences familiar to her readers, who were later disenfranchised by Trilling’s criticism, working-class women whose roles, family structures, economic precarity, and likelihood of experiencing domestic and sexual violence were all impacted by their material conditions.

Even though The Girl has been undermined and ignored by anti-communist literary tastemakers and critics, the poignancy of the female characters’ collective liberation in the novel, as well as its stunning moments of prose, make it a profound document of the power of working class women to take care of each other when no one else will. When the girl finds out about her friend Clara’s illness, she asks Amelia, “I used to go around with Clara and where is she now? Who cares if she had a name even, who cares about her blood and bones, who she loved, the way she walked.” Amelia responds, as if LeSueur herself is speaking directly to her readership: “All that knew what she knew. All that feel the same, they are together, all with hands like that from working their enduring life.”