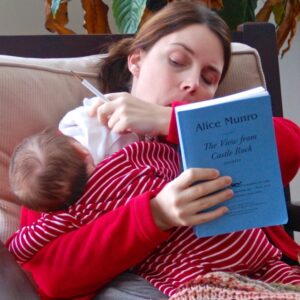

Mother-Reader

In retrospect, I did everything wrong when I opened Emma Donoghue’s excellent story collection Astray. I didn’t check the author notes explaining the origins of each piece. I didn’t note the time: midnight. It didn’t occur to me that in a collection chronicling historical moments, there might be violence, even atrocity.

So, after the story narrated by Jumbo the Elephant’s charming keeper, and the complex piece about a Dickens-era mother turning tricks while her child naps, I turned to “The Hunt.” Set during the American Revolution, the story follows a German boy forced into military service where he’s urged, over several days, towards a horrific attack on a girl. Later, in my fiction-writer and professor modes, I would marvel at Donoghue’s technique, the ways she builds the action to a devastating shock. The story is masterfully paced; I could, theoretically, teach it.

But to do that, I’d have to switch off my other, newer mode of reading—the Mother-Reader—which at 1 a.m., after closing the book, directed me to curl up in my six year-old daughter’s bed and keep vigil until the sun rose.

Parenthood has changed my life in all the expected ways. But an unexpected change has affected the way I read. Where I once read and taught writing in terms of its construction—How is this thing made? How is it working? Who is it for? Why did the writer make this choice? —I now often find myself inside the building itself, checking the locks on every door.

Artworks, Waterworks, Fireworks

My shift into Mother-Reader happens without warning. Prepping a story I’ve read multiple times—like Maxine Hong Kingston’s “No-Name Woman”—I suddenly weep over the mother who drowns herself and her newborn in the well. After years praising Flannery O’Connor’s technique in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” I clench when the Misfit directs his henchmen to take the family, one by one, to the woods. Now I could be that cabbage-faced mother accompanying those bratty (but still loved!) kids. (Someone has to love them, right?)

What’s wrong with me? Is this unusual? As it happens, a number of writer-teacher-readers report that their connections to reading—to any art, in fact—became more intense after parenthood. “Emotional” is the word they use the most.

For example, Ploughshares’ own Ian Stansel says that since becoming a father, “as far as reading goes, I’ve found that I’m more easily emotionally swept up in a story than before, especially if it has to do with children. It isn’t exclusive to writing, either. Soon after my daughter was born I was driving and listening to The Beatles’ ‘Octopus’ Garden’ and I started crying at the bit about all the children being happy and safe.”

And we don’t just weep— sometimes, a moment of parental fatigue or joy unexpectedly resonates. After his first son was born, poet Gary Leising “got a completely different feeling about Plath’s motherhood poems. I had always read her sense of disconnection from her children in ‘Tulips’ or ‘Morning Song’ as somewhat creepy, but I also saw the new-parent experience in those poems as coming from sleep deprivation. And after hearing Michel Faber’s story ‘Vanilla Bright Like Eminem,’ I rushed to put it on my syllabus, only to have the students appreciate its emotional power so much less than I did. Why didn’t they weep as the father moved through the happiest moment of his life?!”

The Cold Comfort of Craft, The Hot Mess of Emotion

Of all the ways I usually talk about reading, “emotion” doesn’t even make the top ten. For over twenty years, most of them childless, I’ve deployed multiple lenses, theories, and histories to think and talk about creative writing, women’s memoirs, African American literatures, Caribbean literatures, and ghost stories. Much of my subject matter is agonizing. In the classroom, I push students to view writing as something crafted—not as a sociological document but as a work conceived by an author, aimed at reading audiences, created at a certain point in history. “Tell me something about this novel besides ‘I like it,’ or ‘It made me mad,’” I say—nudging students past emotional reactions.

Because, as Dorthea Brande tells us in Becoming a Writer, this is how you “Read as a Writer.” Reading is purposeful. You don’t just sit there, feeling things. You do something with your feelings. As Brande writes, “Anyone who is at all interested in authorship has some sense of every book as a specimen, and not merely as a means of amusement.”

And you can’t dissect a “specimen” of writing if your eyes are blurry with tears. You can’t write with snot splatting the page. You can’t launch salient points with a quaver in your voice.

Right?

At this point, I feel the need to assure you that I’m not a robot. Yes, I’m an affable, repressed Midwesterner—but I still react emotionally to writing. I am Pro-Feelings!

Still, as with many professional readers and writers, the act of reading for me is inextricably linked to the act of analysis. Reading for pleasure is also reading for learning—for myself, or for hundreds of other people. There is almost no text (yes, even Us Magazine counts as a “text,” which is sort of nice) that I don’t, at some level, hold up to the light, consider for cut and clarity, and catalog for possible future use.

Reading is stirring; it’s also my livelihood. Writing is wrenching; it’s also my profession. Emotion is fodder for teachable moments; and yet, emotion could undermine my authority. The only thing I remember about a certain choir teacher in high school? That she left the classroom crying. It was never something we felt responsible for, although we—a bunch of jerky kids—definitely were. Instead, we assumed this teacher, this woman, was unfit to lead a class.

So the Mother-Reader—full of outrage, warnings, righteousness, tears—unnerves me. What if she barges in some day in while I’m lecturing on Beloved?

“Art is the Rorschach test for all of us”

The Mother-Reader, so far, has only briefly visited. Last spring, I asked my American Ghost Stories class, “Is anyone scared of ghosts these days?” My students—mostly in their early twenties, and very few parents among them—laughed about creaking doors, cemeteries, spooky nights in the woods.

Then they asked, “What about you, Dr. Meacham? What freaks you out?”

I answered as a parent—which, by definition, ended all the fun: “My worries? Home invasions. Losing our health insurance. Something happening to my kids.”

But if I think more deeply about it, to my Ghost Stories students I only revealed my newest secret self. In her essay, “This is Our World,” Dorothy Allison writes, “If we were to reveal what we see in each painting, sculpture, installation, or little book, we would run the risk of exposing our secret selves, what we know and what we fear we do not know, and of course incidentally what we truly fear. Art is the Rorschach test for all of us, the projective hologram of our secret lives.”

Before I had children, my secret life seemed different. Reading for my doctoral exams, I loathed John Updike’s Rabbit Run because I recognized Rabbit. In fact, I’d married him—and now he was contesting our divorce. Ugh, I hated that guy. I couldn’t separate my facts from Updike’s fiction. As I hid my unraveling home life from my peers and professors, I put the book down, picked it up, screamed at it, put it down.

Now that I’m happily remarried, would I feel the same about this novel? I’ll never know, because as I recall, there’s also a scene of a baby’s bathtub drowning at the hands of a mother.

So that one’s still off the list.

Allison’s essay makes me wonder, though: maybe our experiences of art are larger than the most recent “Life Event” on our timelines. Maybe, for me, becoming a parent didn’t create anxiety. Instead, maybe parenthood is just the new face of old fears, hatched in my childhood, over issues of control: controlling my private life, controlling my public self, and now, controlling my professional identity.

Writer Diana Joseph, who introduced me to the Allison essay, puts it beautifully: “As a reader, I never see myself in the mother characters. I see myself in the vulnerable kids, and I find myself drawn to stories about vulnerable kids. Even though I’m aware that my son is vulnerable because he’s a baby, I’m also aware that he’s powerful because I’m his mother. Being his mother makes me feel vulnerable.”

Years ago, I mocked those bright yellow rear-window signs, wondering, What did those drivers want me to do differently just because their kids were in the car? But maybe those signs were never for tailgaters. Maybe those signs were placed by the drivers, the parents, as amulets: charms to help carry them past their greatest points of vulnerability. Certainly I’d welcome any kind of compass, particularly late at night, inside a house locked tight. Because even something as simple as reading a book can take you somewhere unexpected with a Baby On Board.