Netflix’s New Joan Didion Documentary Speaks to Pain and Memory

I cannot watch a documentary about Joan Didion impartially any more than her nephew, Griffin Dunne, could make an impartial film about his legendary aunt. To say that Didion, now 82, has had an impact on me as a young, female, native Californian who writes creative nonfiction is to gloss over the depth of sensibility that shapes our early identities.

Netflix released Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, directed by Dunne, on Friday. It is a celebration of her life and work, and opens with Didion talking about snakes, saying they always appear in her work because they were always on her mind. They were something to avoid when growing up in California. She asks Griffin, behind the camera, if he has snakes up in the country.

“I just take a rake and kill it,” he tells her.

“Killing a snake is the same as having a snake,” she tells him. They both laugh because she is right. Killing the thing still means confronting the thing, and continuing to confront it every day whether you see it or not.

The Center Will Not Hold makes Didion the subject–an elegant twist from her usual seat as the observer. She tackles all the things we refuse to confront: the Manson murders, America’s involvement in El Salvador’s brutal civil war, and the deaths of her husband and daughter. “If you kept the snake in your byline,” she says later in the film, “the snake won’t bite you. That’s how I always felt about pain. I wanted to know where it was.”

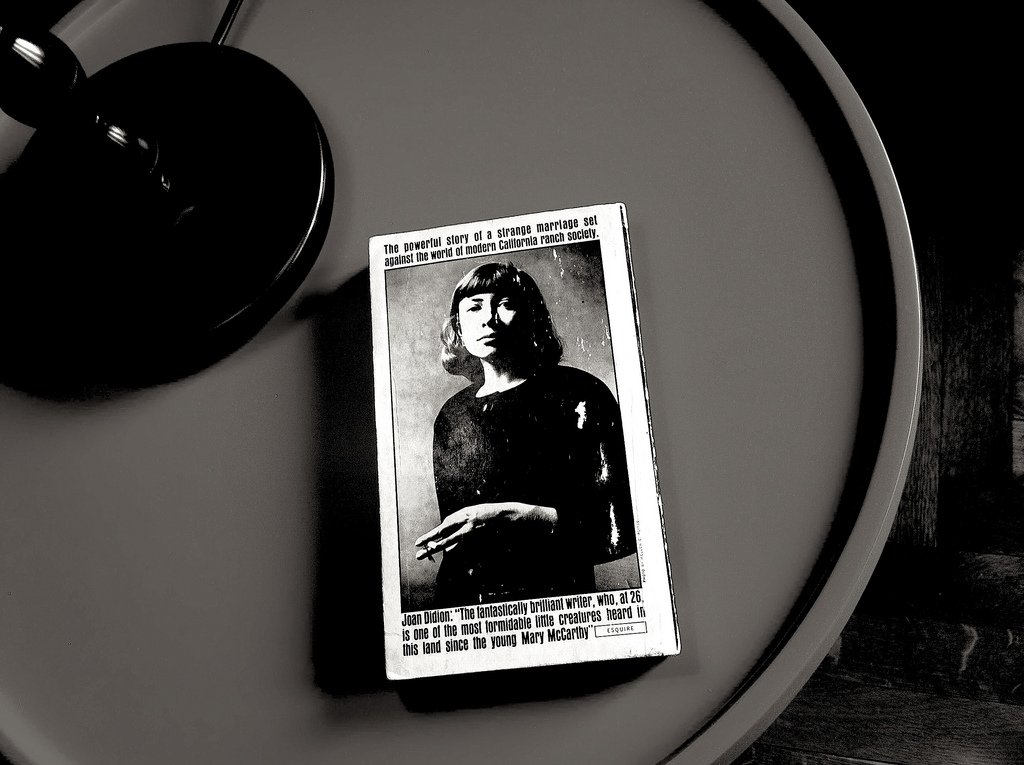

As the subject of a documentary, Didion seems comfortable–perhaps because her nephew and grandniece, Annabelle Dunne, are the filmmakers, or perhaps because she knows that her books are now hallmarks of American literature. Her glamour in the iconic photographs that flash onscreen—the oversize sunglasses, the velour maxi dress as she leans against the Corvette, the cigarette and scarf—are just as much an indicator of her intellectual style as her books. She is a writer who doesn’t mind having her picture taken, or having the camera follow her through her house or the park, or speaking unsparingly about her darkest days and her distant memories of the golden ones.

As we watch her walk through her house, full of photographs of her family, we see the ways in which memory, like pain, is inescapable. She takes us back to Los Angeles, where she and her late husband lived in the early days of their marriage after Didion was sick of New York–then to the parties on Franklin Avenue where they raised Quintana, and to the home in Malibu that saw a young Harrison Ford as its carpenter.

We see her reminiscing with Vanessa Redgrave, who played Didion in the Broadway adaptation of her 2005 National Book Award-winning memoir The Year of Magical Thinking. The two look at Redgrave’s family photo album and find pictures of her daughter Natasha marrying actor Liam Neeson. Didion and Dunne were guests at the wedding, and since then, both Natasha and Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne have died. The camera pans out, framing two women who have made remarkable contributions to American culture and who have both buried their beloved daughters. This scene, one of the documentary’s most moving, situates Didion’s memories of the past as both a cause of and balm for her pain now.

In the end, Didion speaks about her life as she writes about it—with lucidity and grace. She may not have planned for misfortune, but she matter-of-factly holds it up to the camera, turning it until it catches the sun. Without her vulnerability, we might not see her strength.