Non-Writing Things that Nevertheless Help Me Write: Steve Martin

When I told a friend my idea for these posts, she said, “That’s great. Post 1: beer. Post 2: scotch.” This rather snarky answer actually reinforced one of my goals for these admittedly egotistical pieces: all writers have their crutches and vices, and while alcohol is often one of them, there are others. I swear.

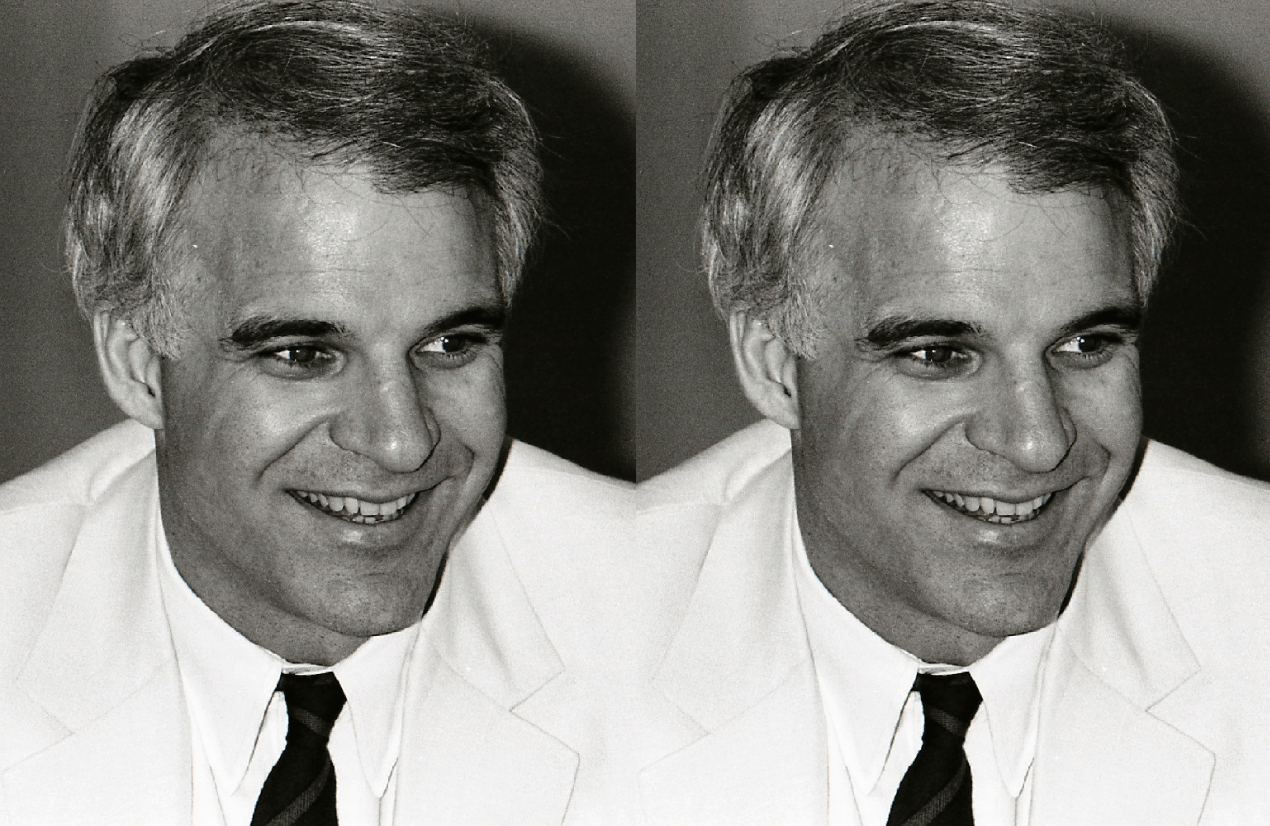

I’d also like to discuss the fact that while reading books and short stories inspires me a great deal, it’s only part of what makes me want to write. It’s fine for people to imagine me (though why one would ever imagine me at all is beyond me, but please go with it) sitting in an oak-paneled library surrounded by leather-bound tomes, chewing thoughtfully on a quill as I read through the fictions of the day, and of course, I do. Like many, I have been critical of the sudden proliferation of aspiring writers who don’t like to read. However, I get inspiration from music, movies, art, and even, gasp, television. Writers don’t have to look down on all other forms of art. Reading is, by far, the best way to learn to be a writer, but it can be supplemented by other, more lowly forms of expression.I saw Steve Martin read with Ian Frazier in New York City at the Bowery Ballroom in 2002. I’ve been to readings where almost everyone cried, and I’ve been to readings where almost everyone laughed, and I’ve been to readings where almost everyone felt sick, but Martin/Frazier remains the one and only reading I have been to where almost everyone laughed until tears streamed down their face and they felt nauseous. I thought for a few minutes that I might actually have to leave; I didn’t know if I could take it. Something was going to give. Luckily, it did not, but the reading continued like a prizefight, with each writer reading short pieces with increasing energy and increasingly hilarious results.

After the reading, my mother and I walked up the dim stairwell to leave the building (we’d waited until the room was almost empty, and I have some vague recollection of one of us having a sprained ankle or something), and, standing by the door like a regular person, was Steve Martin. It is the one and only time I have been starstruck. I couldn’t say anything and walked past him like an idiot.

I think about this failure on my part a lot because I am a lifelong Steve Martin fan. I own first editions of all his books (including Cruel Shoes) and have owned Pure Drivel in three formats (tape, CD, MP3) and all of his comedy albums in four (add vinyl to that list). Whole sections of my life can be blocked off by Martin’s films; my friend Brooks introduced me to The Man with Two Brains, All of Me, and Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (our favorite, featuring the line, oft-repeated by the two of us, “Carlotta was the kind of town where they spell trouble T-R-U-B-I-L, and if you try to correct them, they kill you.”) when I was probably seven or eight, but somehow I didn’t become obsessed with The Jerk until college. When I became very obsessed. A trip to The Three Amigos brought me some friends in a new town when my family moved when I was ten. And on it goes, as most recently I watched old clips on YouTube in the library of Yaddo with a similarly-obsessed fan.

It’s difficult, I think, for people who are not old enough to remember the 70s (I cannot) to understand how gigantically huge Steve Martin really was. He was selling out stadiums—stadiums!—and his albums went platinum and multi-platinum, numbers that have become an endangered species in the record industry. But what’s even more difficult to understand now is how he took an entire art form, stood back from it, and then reshaped it into something different. In this way, and I know this sounds ridiculous, Martin is like Picasso. He looked at things in a completely new way, but in order to do so had to understand how they were done at present.

At the heart of all of this is a sincere and abiding love of words. Steve Martin adores words. How many combinations did he have to try out before hitting upon the one—Gern Blanston—that would seem funniest as his real name? Listen to him read Pure Drivel and you can hear by the way he enunciates how carefully he selected each word for its rhythm and weight.

The way Martin toured, and as hard as he worked, it would be fascinating to see a transcript of an early show on the tour and then one towards the tail end. The amount of editing is staggering. Each joke—and this is certainly true of other comedians as well—gets honed and polished and expanded and tightened over hundreds of retellings. Martin’s reaction to someone (or hundreds) shouting out the punch lines to his jokes is well documented: it threw him off. Everything had been so fine-tuned, each gesture and pause so finely calibrated that the smallest grain of dirt in the machinery could create a hitch. Sometimes when I think of my novel going through yet another revision, I think of this, and remind myself to be thankful I don’t have to reshape each draft in front of a crowd.

Perhaps even more than any of his individual skills, Martin’s varied life gives me inspiration. He’s been the biggest standup in the world, a comedic actor, a dramatic actor, an art collector, a playwright, an essayist, a fiction writer, a screenwriter, a director, a producer, and to top it all off, in those early movies, he was in damn good shape. Obviously, he’s a tremendously gifted individual, and hyper-intelligent, but his work ethic is unfathomable. For one person to break through in several notoriously closed-off art forms, he had to earn it. And he did.

So while I’m sitting alone at my desk, bemoaning rewriting an ending for the fifth time, I think of Steve Martin, out on the road, telling a joke for the two hundredth time, still working on it, and I straighten up and get back to it. If I have the opportunity to meet him again, I will tell him what he’s done for me. Or I will completely panic and walk past. I’ll let you know.

Image: Steve Martin (Towpilot, 1982)