Not Like One of the Family: Novels of Dignity and Domestic Labor

The myth of Rosie the Riveter is as well-known as her bandana-clad hair and stoic flexing. As a way to supplement male industrial labor resources depleted by World War II, Rosie represented the potential for women economically left behind since the Great Depression to gain financial power over their lives. But the reality of the re-gendering of American manufacturing, like most American narratives, imagined a white face as the beneficiary of industry.

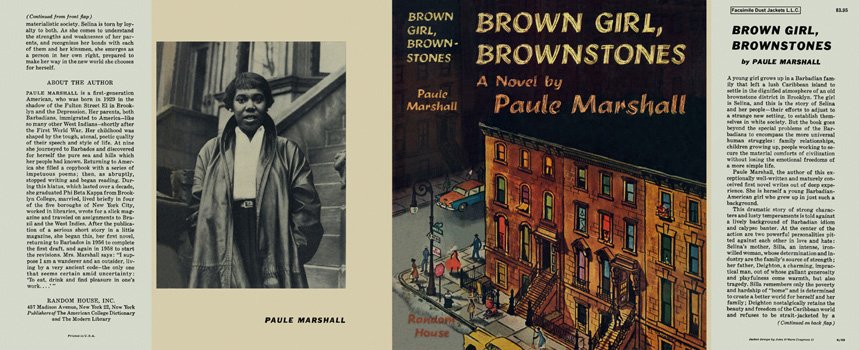

Paule Marshall’s 1959 novel Brown Girl, Brownstones opens on the eve of America’s entry into World War II as one of the story’s main characters, Silla, is cobbling together a living as a domestic worker for white families. A Barbadian immigrant, Silla longs to purchase her own brownstone to create a stable and permanent life in the United States for herself, her husband, and her two daughters. Told from multiple characters’ points of view, Silla’s main foil is her bright and outgoing daughter Selina, in whom she invests all hope of a prosperous American future. But Selina, caught between her Barbadian heritage, her American adolescence, and the prejudices of American-born Black people, views her mother as just one in a sea of embittered domestics like her:

They were all alike—those watchful, wrathful women whose eyes searched and searched and laid bare, whose tongues lashed the world in unremitting disgust. Each morning they took the train to Flatbush and Sheepshead Bay to scrub floors. The lucky ones had their steady madams while the others wandered those neat blocks or waited on corners—each with her apron and working shoes in a bag under arm until someone offered her a day’s work.

Silla, like the more than 60 percent of domestic workers in the 1940s-1950s who were Black women, faced the stigma of their occupation in both the homes they worked in and the homes they created for their families. White employers frequently considered their Black domestics as nominally-paid extensions of slave era mammies. Domestic workers (as well as farm workers) were excluded from the landmark 1935 National Labor Relations Act and the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act. While the predominantly white industrial workers were gaining the right to collective bargaining and the forty-hour work week, Black and Latinx workers frequently faced long hours, dangerous or time-consuming jobs outside the scope of their prescribed duties, and life without the guaranteed income or job security of industrialized workers.

Alice Childress’s 1956 novel, Like One of the Family: Conversations from a Domestic’s Life (reissued this year by Beacon Press with a foreword by Roxane Gay), addresses the difficulties Black women faced in the non-unionized market of domestic labor. Childress, drawing from her experience as a successful actress and radical Black playwright, stages the novel as a series of monologues delivered by main character Mildred to her friend, both domestic workers. Using her wit as a tool for battle, Mildred not only sets right her employers on their misguided and self-absolving notion that the Black women they employ are like one of the family, she also encourages other Black domestics to unionize. Originally published as a serial in Paul Robeson’s radical journal Freedom, Childress, a fellow traveler (or possible Communist Party member), encourages her readers to:

March up and down in front of the apartment house carryin’ signs which will read ‘Miss So-and-So of Apartment 5B is unfair to organized houseworkers!’ The other folks in the building will not like it, and they will also be annoyed ’cause their maids are out there walkin’ instead of upstairs doin’ the work. Can’t you see all the neighbors bangin’ on Apartment 5B!

But the very nature of their work made it difficult for domestics to organize, as each woman was isolated from other workers within the separate homes of their employers. Still, word of mouth about domestic organizing spread through conversations on buses and ads posted in laundry rooms and in papers like Freedom, until 1974 when the Fair Labor Standards Acts was amended to include a minimum wage for domestics.

Unlike Mildred and many other World War II-era Black women, Brown Girl’s Silla is able to obtain a job as a lathe operator at a defense factory in the “barren waste land” of Williamsburg, Brooklyn. But Silla’s transition from a domestic to an industrial worker with the full protection of her union is not the same as the prevailing Rosie the Riveter myth. In fact, the inclusion of middle-class white women in the wartime workforce facilitated a greater demand for Black domestic work, and Black women faced employment discrimination on the grounds of both their race and gender, frequently being turned away from jobs or offered only the lowest-skilled and lowest-paid positions.

Yet Silla’s opportunity to obtain work in the munitions factory gives her daughter, Selina, the chance to witness her mother’s dignity as she strives to make a living for her family:

Silla worked at an old-fashioned lathe which resembled an oversize cookstove, and her face held the same transient calm which often touched it when she stood at the stove at home . . . Watching her, Selina felt the familiar grudging affection seep under her amazement. Only the mother’s own formidable force could match that of the machines.

Selina’s perceptions of her mother’s strength shines a light on the dignity of mid-century Black women striving to work, provide, and organize—in the factories and white women’s homes and the myriad of other places they could find employment despite the racism and sexism they faced. “Domestic workers have done an awful lot of good things in this country besides clean up people’s houses,” Mildred says to another domestic ashamed of her occupation. “We’ve taken care of our brothers and fathers and husbands when the factory gates and office desks and pretty near everything else was closed to them.” Silla’s dream of owning a home never comes to fruition, but her hard work pays off in her daughter’s creative and intellectual endeavors as she grows into adulthood. Selina, finally able to ascribe dignity to her mother’s work, is free to find dignity in her own.