Notes on the State of Virginia: Journey to the Center of an American Document, Queries VII, VIII, and IX

This is the fifth installment of a year-long journey through Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia.

**

Query VII: A notice of all that can increase the progress of human knowledge

Query VIII: The number of its inhabitants

Query IX: The number and condition of the militia and regular troops, and their pay

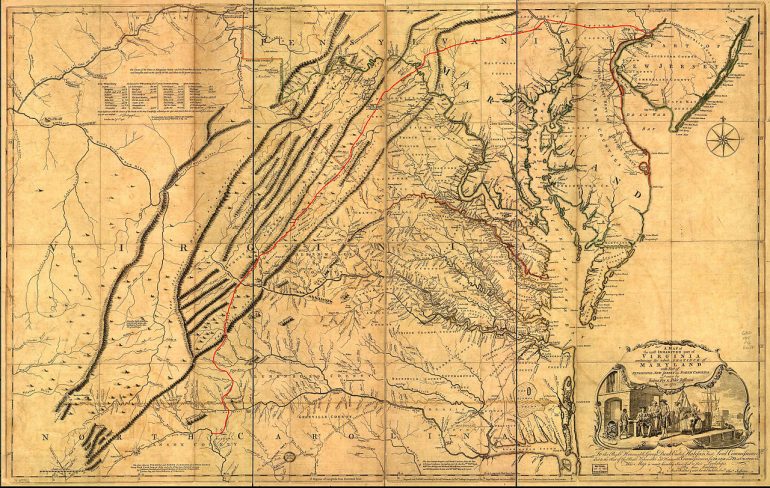

In these three queries, Jefferson attempts to distill the complex meteorological, demographic, and military features of Virginia into a series of data points. His prose—supplemented by graphical tables tracking everything from rainfall to carriage wheels—draws a fine grid over the natural and human activities of the Commonwealth. These particular sections of Notes bridge Jefferson’s study of natural law with his meditations on systems of government, so it makes sense that tabulation is the main rhetorical strategy here. Jefferson values numbers as a means for describing all sorts of observations—elemental, mechanical, animal, etc.—and for delineating change over time.

In much of Anglophone poetry, accentual-syllabic verse organizes language (yes, even free verse!) into stressed and unstressed syllables. Like Jefferson’s tabulations, a poem’s meter, or system of accentual stress, makes a compositional pattern that we can observe and experience over time. Meter divides and unifies a poem, making the space of the page a contained realm within which the mind of the poet may move like weather. Scansion is the practice of measuring and describing the metrical patterns at work in a poem, but you can apply its principles to any unit of language. One of my favorite teaching activities is to have students scan their own names to find the metrical music in them. Thomas, for example, is a trochee because it’s comprised of a stressed first syllable and an unstressed final syllable. The inverse of a trochee is an iamb, a pattern that some scholars believe mimics the natural patterns of Anglophone speech or even the da-DUM of a beating heart. The trochee, by contrast, is more performative. It has roots in the Greek term trokhaios pous, the running or spinning foot.

So, our Thomas is a sprinter.

For Jefferson, time moves forward with propulsive energy. It’s this energy that drives Virginian civilization toward greater environmental stability, economic prosperity, and social refinement In Notes, bodies meet weather, weather meets math, and math meets argument. Jefferson’s mind and body are ever-calculating instruments of observation, as in this excerpt from Query VII:

Going out into the open air, in the temperate, and warm months of the year, we often meet with bodies of warm air, which passing by us in two or three seconds, do not afford time to the most sensible thermometer to seize their temperature. Judging from my feelings only, I think they approach the ordinary heat of the human body. Some of them, perhaps, go a little beyond it.

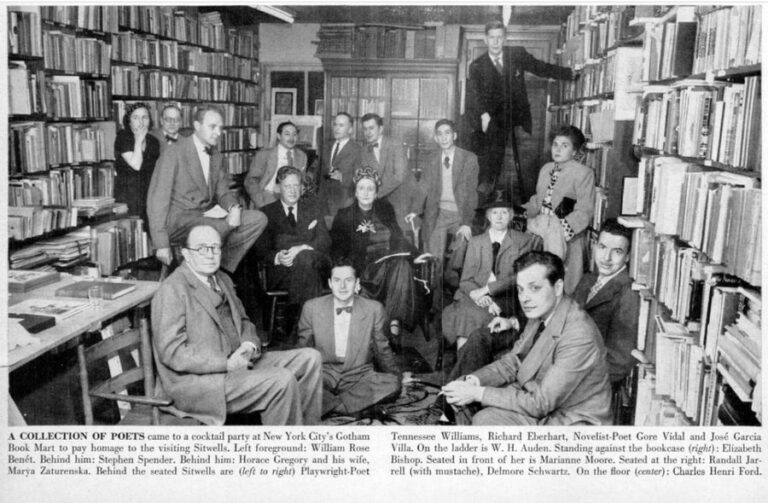

Jefferson loves “temperate” things. He loves moderation, balance, symmetry, and smoothness. In Query IX, he proudly describes the state militia as a series of identical chains-of-command. The militia is comprised of companies, which are divided into smaller battalions headed by colonels. Every county in Virginia has a militia, and every county militia is led by a county-lieutenant. Jefferson deliberately evades Marbois’ question about the “condition” of the soldiers, saying that this is “constantly on the change.” By condition, Jefferson probably means “social position or rank.” His silence is a neat trick, since we know that “free mulattoes, Negroes, and Indians” were permitted to enlist in the Virginia militia, but only in “servile” capacities and without the benefit of arms. I think of these men as the “bodies of warm air” that Jefferson observes without measuring—present and absent, their lives just “a little beyond” the egalitarian vision he wants to spin for the French.

Instead, Jefferson uses his “tabulations” to illustrate Virginia’s increasing order and harmony. The meteorological obsessiveness of Query VII, presented as the answer to Marbois’ question about “all that can increase the progress of human knowledge,” only makes sense when you remember that Jefferson wants to affirmatively connect the processes of nature to those of the human world; he wants to prove that both Virginia and its people are on the right track.

For Jefferson and his contemporaries, the proper way to prove a hypothesis is through scientific observation. In Query VII, Jefferson’s meticulously crafted weather table averages five years’ worth of climate records across three categories. Jefferson reports having taken hundreds of readings on wind direction alone. This scientific labor is for a purpose: to show the reader how the land itself is “progressing,” becoming more hospitable to Virginian agriculture. Jefferson’s tables show, for example, that the Commonwealth’s climate, especially in “the neighborhood of Monticello,” has mellowed considerably over the years. No more deep snows, Jefferson boasts. No more crop-killing early frosts. Everything grows here. Like the syllables of a metrical poem, the seasons conform to their rightful places in the calendar.

Am I the only one who finds this aesthetic kind of terrifying, though?

Take the Monticello tour sometime. Jefferson’s magnificent gardens are terraced into the mountainside. The mansion exists uphill, at the apex of things. Between Jefferson’s house and his garden is another terrace known as Mulberry Row. This is where Jefferson’s slaves lived and worked. From Mulberry Row, the slaves could quickly reach the garden to work, or report up to the house when called. When I visited Monticello, I stood at the door of a replica slave cabin and looked up and down the slope. I realized that while I could just see the rear curve of the house, most of it was half-hidden in the trees. It occurred to me that you could live in the mansion without witnessing much, if any, of the slaves’ domestic lives. Likewise, many slaves’ experience of Jefferson’s acutely curated estate must have been limited to the proscribed paths their labor obliged them to travel. The organized spaces of Monticello—its interlocking rooms curled into each other like a seashell, its terraces descending down the mountain—deliberately keep you from seeing everything.

So, when I try to read Mulberry Row like a line of verse, the result is far less satisfying than my exercises in scansion. While order, constraint, and containment may have generative properties for a poet, the human spirit wants to escape, no matter how beautiful the terrace. I struggle with Jefferson’s project, in Query VIII, to describe the human population of Virginia by means of tabulation. People can’t be measured like barometric pressure. Jefferson’s neat column of taxable articles (“free males,” “slaves,” “horses,” “cattle,” “wheels of riding-carriages,” and “taverns”) rankle, as does the way he distinguishes between the “importation of useful artificers” from other (presumably European) countries whom Jefferson believes would contribute to Virginian culture, and the slaves who are already contributing to that culture on the other side of his mountain. While Jefferson confirms that no more slaves will be imported to Virginia from Africa and uses this fact to predict a distant, future end to “the moral evil” of slavery, his taxonomical mind still wants to count, categorize, and divide (non-white, non-male) human beings into hierarchies.

I’m not cool with that.