Olive Kitteridge and My Mother

Olive Kitteridge is an infuriating character, as real a person as I’ve ever seen on the page. Her missteps with those closest to her accumulate from the beginning of Elizabeth Strout’s celebrated novel. She finds people endlessly disappointing and lashes out at them for reasons that are usually known to her, but are rarely known to them. In the first chapter, her husband, Henry, is always alert to her moods. “He wanted to put his arms around her, but she had a darkness that seemed to stand beside her like an acquaintance that would not go away.”

Olive Kitteridge is an infuriating character, as real a person as I’ve ever seen on the page. Her missteps with those closest to her accumulate from the beginning of Elizabeth Strout’s celebrated novel. She finds people endlessly disappointing and lashes out at them for reasons that are usually known to her, but are rarely known to them. In the first chapter, her husband, Henry, is always alert to her moods. “He wanted to put his arms around her, but she had a darkness that seemed to stand beside her like an acquaintance that would not go away.”

Olive loves deeply, but she’s unable to love the people closest to her in the way they want to be loved. In perhaps the saddest chapter, Olive’s visit to her adult son ends abruptly when he tells her, “Mom, I’m not going to take responsibility for the extreme capriciousness of your moods.” Olive is seventy-one by this point, and Henry is in a nursing home, paralyzed and unable to speak after a stroke. In the course of an ugly fight, her son tells her he won’t be ruled by his fear of her. Olive is astonished that he’s afraid of her and recognizes that she’s the one who’s afraid, but she doesn’t name her fear. Unable to understand what she’s done wrong, she refuses to apologize to her son and fails, once again, to connect with him.

It’s with this failure in mind that the reader encounters Olive in the final chapter, seventy-four and a widow. Henry has been dead for a year and a half. Every morning, Olive walks six miles on a path that runs along the river. It’s the “best, and only bearable, part of the day […] Her one concern was that such daily exercise might make her live longer. Let it be quick, she thought now, meaning her death—a thought she had several times a day.”

Each day, Olive runs down the clock until she can go to bed with the sun. She has her routine, but it feels purposeless. Olive made me wonder if the days felt like this to my mother after my father’s death. He died twelve years ago, from a neurodegenerative disease that slowly compromised his mobility. For the final year of his life, he was bedridden, and my mother was rarely able to leave the house. It was as miserable and exhausting as it sounds, and by the time his death came, we’d been hoping for it for months. But still we were bereft, in disbelief that he was really gone from the world and at loose ends without his needs to attend to.

I had a job, and I went to the office, dragging myself out of bed each morning and struggling to perform the most basic tasks. Work filled the hours, and my husband helped me adjust (slowly) to life without my dad. He made me dinner and comforted me when I cried. My mom had friends and interests, and she made plans most days. But every time I saw her, she told me how much trouble she’d had getting out of the house that day. She kept trying to do one more thing—pay a bill or organize a drawer. And then the phone would ring, or she’d make it out to her car only to realize she’d forgotten something and had to go back into the house, where she always discovered something else that needed doing, but she never finished anything. She struggled to find direction in this new part of her life, and the house she’d shared with my father kept pulling her back in. Olive struggles with the emptiness of home, too. Rather than rattling around the house like my mother did, she leaves it at sunrise to start her morning routine. When a week of rain prevents her from being able to take her walks, she calls them “hellish days.”

Without my dad to take care of, my mom finally had time to see her doctor, who discovered that her back pain was caused by severe arthritis in her hips. She had two hip replacement surgeries just a year after my father’s death, and focused on the task of recovery. She was back on her feet in record time and signed up for ballroom dancing lessons without a partner, which struck us all as exactly the sort of bold and optimistic move that was needed, but it went badly. In ballroom dancing, you really do need a partner.

She found one several years later, in Tom, a recent widower. They’ve been together for eight years. The final chapter of Olive Kitteridge is the story of Olive finding a partner after Henry, and I recognized much of my mom’s yearning in it. On a walk by the river one morning, Olive encounters a man she knows of collapsed on the path. He’s about her age, and she helps him up, in a forlorn meet cute. They talk about death immediately, and before they leave the river, he tells her his wife died a few months ago, and she recognizes that he’s in hell. She’s never thought well of the man from what she’s heard of him around town, but she takes him to the hospital, and waits while he’s seen. A week after the incident, she realizes,

[…] The time spent in the waiting room while Jack Kennison saw the doctor had, for one brief moment, put her back into life, And now she was out of life again. It was a conundrum. In the time since Henry had died, she had tried many things. She had become a docent at the art museum in Portland, but after a few months, she found she could hardly endure the four hours required for her to be in one place. She had volunteered at the hospital, but she could not bear wearing the pink coat and arranging dead flowers while the nurses brushed past her. She had volunteered to speak English to young foreigners at the college, who needed simple practice with the language. That had been the best, but it was not enough.

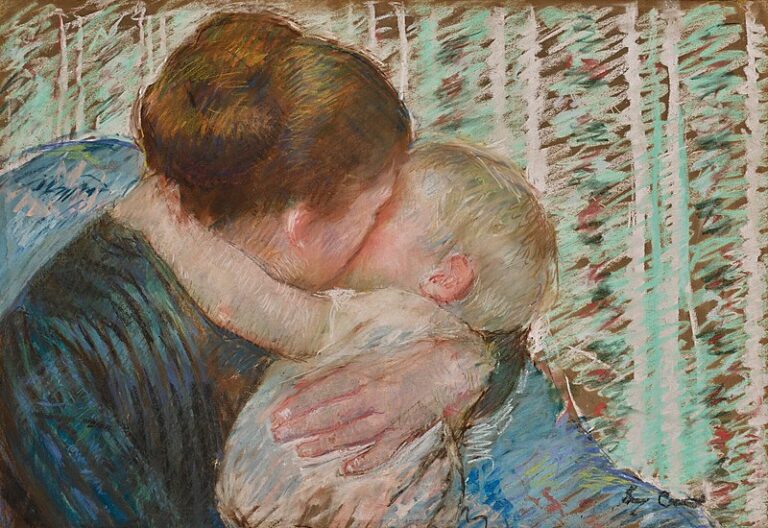

My mother isn’t Olive, but through Olive I saw vividly, for the first time, what those early years after my father’s death must have been like for her. She tried to go back into life, and enjoyed some activities and relationships, but it was not enough. Two years after my dad died, my husband and I had a baby, another bold and optimistic move. He arrived early and had difficulty nursing. My mom rose to the occasion, sleeping over on our lumpy futon to help with nighttime feedings. He delighted her as he grew, and she saw him often, but he wasn’t part of her daily life.

She met Tom about a year after my son was born. Shortly after they met, my family went on vacation in Maine with her (right down the road from Olive’s fictional town). I watched her face light up every time he called. She went for long walks along the beach, talking to him, and returned brighter. My dad’s slow decline lasted for twenty years. I’d never seen my mom this hopeful. I worried that if it didn’t pan out, the disappointment would be hard to come back from, but Tom has become part of our family.

Olive’s relationship with Jack doesn’t proceed as smoothly. In a familiar pattern of behavior, she insults him and pushes him away, but in the weeks that follow, she misses having him to talk to, thinking, “It was terrible […] when you couldn’t tell people things.” She reaches out to him, coming as close to an apology as she can manage. Her failure to connect with her son earlier, and the conversations she’s had about their fractured relationship with Jack, make this moment of change possible.

His blue eyes were watching her now; she saw in them the vulnerability, the invitation, the fear, as she sat down quietly, placed her open hand on his chest, felt the thump, thump of his heart, which would someday stop, as all hearts do. But there was no someday now, there was only the silence of this sunny room.

Olive knows how it ends, but she chooses love because she realizes it’s her only way to remain in the world. Just as Olive’s life is better with Jack in it, I know my mom’s life is better with Tom in it, but I’ve worried privately about the obvious risk. One of them is going to die first, and then the other one will be right back in the middle of grief again. And there’s an even worse scenario—the long illness, the caregiving and exhaustion, and then (still) the terrible grief. But no one knows this better than my mom.