On Master Suffering

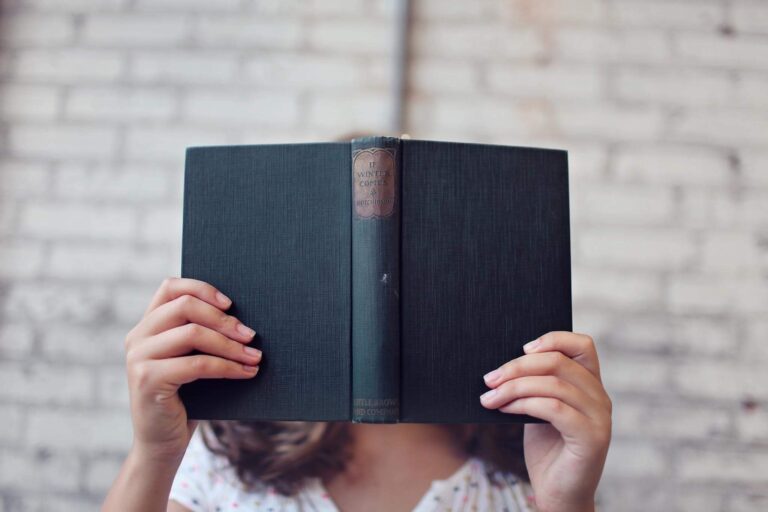

CM Burroughs’s Master Suffering hinges on relating: to a sexual partner, to a lost sister, to friends discussing God, to the reader—or is it the lover?—who is directly addressed, asked for understanding, in poems like the one called “III.”:

![excerpt of poem "III" that reads: I want you to understand what this bracket feels like: [ ] Be an active participant in the difficult narrative of body. Fit your body into the [ ]](https://pshares.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Screen-Shot-2021-03-13-at-2.06.18-PM.png)

This request for bodily understanding, explored in the series of numbered poems near the collection’s opening, opens the speaker’s body to the addressee’s view: “Do you want / to look inside?” The poems pivot among first, second, and third person, raising questions about self and other, layering a palimpsest of relationships.

These poems, in other words, invite intersubjective understanding, even “so much empathy,” while also insisting on the speaker’s self-ownership, the space between self and other. They interrogate mastery and also resist it; the collection is rife with rich ambiguities. In this way, the book also hinges on its title’s ambivalence. As Evie Shockley asks in her endorsement, is Master Suffering “A directive? Or a direct address?” Does suffering master the grieving, conversing, lovemaking woman at the collection’s center or does she seek to master it? And if she seeks such mastery, does she succeed?

The tight collection is divided into three sections. It opens with a number of poems about sex and interpretation, moving into an admission of the book’s primary particular grief—the loss of a sister—and a series of poems questioning the possibility of God in light of senseless suffering before ending in another section meditating on sensual pleasure, self-ownership and self-gift, and bodily salvation. Yet this ostensible order is complicated many times over: as with the pronouns and the relationships, key words work through ambivalence and ambiguity, including the reoccurring signifiers “pain,” “dark,” and “black,” all of which bear both death- and life-dealing valences. Theodicy—the question of God’s goodness in light of human suffering—extends beyond the central section that at first glimpse seems to contain it. From the very start, in fact, the mixtures manifest, as Burroughs transposes the language of faith and the trappings of religion into a space of sensual embodiment. The opening poem, “The Lovers,” which rejects a narrative of sexual alienation and instead tells of a holistic intersubjectivity, begins with an image of the lovers who “form a cross on / the kitchen table.” “Questions During Protest” similarly tells of sexual encounter in a register hinting at religion—“I am an offering”—and “My Home Having Come to This” describes sex as self-giving in words that echo the Christian rite of communion: “Here. My body, my body’s inside.”

In grappling with the tangle of religion, gender, suffering, and sex, Burroughs steps into a centuries-long tradition. For as long as women have been writing in English, they have been writing about these inextricable challenges—back to Julian of Norwich calling Jesus mother and complicating doctrines of punishment and pain in the fourteenth century, down through Aemilia Lanyer in the seventeenth century refusing patriarchal blame of Eve for humanity’s suffering and nineteenth-century feminists rewriting the very Bible to expose false mandates that women must suffer and sacrifice themselves as part of their God-given role. Burroughs herself names more recent interlocutors: Annie Dillard and June Jordan provide enigmatic epigraphs, and the notes highlight several of the poems’ borrowings from other poets, including Gwendolyn Brooks and Elizabeth Bishop. Suffering emerges in the book as a gendered phenomenon. In “Body as a Juncture of Almost,” the speaker connects the “female” and “girl parts” to pain: “Ready to suffer? Predilection for.” Burroughs draws lines between socialized womanhood, suffering, and care, echoing classic lines of feminist thought. In the first of four poems called “Incidents for the Forgettery,” the speaker recounts a frenzy of cleaning and then reflects on how she (mis)hears a man reflect on “a / woman’s functional use” to “serve.” The alleged mishearing perhaps exonerates the man, but the socialized “necessity” carries through other poems in which Burroughs’s speaker describes her propensity to clean as a childhood formation.

Yet cleaning is also a mode of mastery, a way to make order or exercise control. In the third “Incidents for the Forgettery” poem, the speaker narrates the cleaning she undertakes during her sister’s hospital visits, seeking to provide her sister “comfort” and “ease” but also seeking to order the world: “What else could be set right / at the insistence of my hand? When bearing into my training, I could / touch and turn matter into its most masterful self.” Does suffering master the woman bent by grief and socialized service? Or can she master suffering through her efforts to cast order on her world, even if this mode of attempted control carries echoes of gendered oppression? I can’t help hearing Audre Lorde here: Can the master’s tools dismantle the master’s house?

For all her book’s participation in the ancient conversation, however, Burroughs’s voice is singular. Master Suffering is less an intervention in a discourse than it is an inescapably personal truth-telling. Suffering features in the book not just as a gendered and general phenomenon but as arising from an ungeneralizable loss and an individual response to that loss, the most pressing of which is the speaker’s loss at sixteen of a beloved sister after a failed liver transplant. One of the poems titled “Incidents for the Forgettery,” which arrives near the end of the first section, clarifies the speaker’s initiating loss with its unforgettable opening lines

My sister’s body would be felled

by a ruinous liver the size of my

palm and positively

killing a whole person whom I’d spent

my life loving and protecting all the ways

one young body can protect another.

Grief is palpable throughout: in the fifth poem titled “God Letter,” addressed “To Whom It May Concern,” the speaker describes her parents taking the beloved sister off life support in one breathless column of text. “And I died then,” the speaker insists, going on to tell in a run-on sentence of the impossible fusion and partition of saying goodbye, “my face against her face.” The speaker’s suffering extends, in the next poem, into “5 and then 8 years” of undiagnosed depression, another theme that carries throughout the book, including the earlier poem “Wean and Stop,” which describes the body’s illness when the speaker attempts to cease taking antidepressants.

These poems of loss are again overlaid with questions about and to God. In the second “Dear Liver,” poem, the speaker writes, “Given all the prayers against the organs’ recurrent / failure, God became further debatable.” This poem leads, in the collection’s middle section, to the series of “God Letter” poems that grapple with belief and with the problem of suffering in light of avowed divine love and power. These poems follow a trajectory, first addressing friends and referring to conversations about God, then addressing readers with the explicit story of the sister’s death, and finally addressing Godself with the demand, “Why would you put / so much sadness in one person?”

The speaker’s upbringing emerges as traditionally religious—she grew up “in the Baptist church”—but her faith is undermined not only by the unanswered prayers but also the platitudinous prayer of the family’s pastor announcing her sister’s impending death “when he said Sometimes / God has to take back his angels.” The speaker objects not so much to his empty reassurance as to the truth it confronts her with: she “didn’t know it was / coming.” The other “God Letter” poems cast her later questioning in terms of conversations with friends, some of whom hold onto belief: one committed to “Jehova’s unknowable hand” as justification for divine non-intervention, another offering Einstein’s more heady example, embracing “Spinoza’s God” as energy and order in contrast to religion’s “rigid order of ritual.”

These poems evoke peopled dialogues about faith that both critique the cause-and-effect of divine blessing and also suggest an ongoingness to the questioning. After the “God Poems,” though, comes “The Unbeliever,” in which Burroughs’s speaker definitively rejects the idea of God-as-master, horrified by the implications of such a God holding the power to relieve suffering and refusing to do so. If any God exists, this God must be the subject of other people’s faith; the speaker will converse and wonder but leave that faith to others, for

There are no good answers for trauma, only

He’ll never give you more than you can bear, which is

a bald-faced lie. He does, everyday, failings too

cacophonous to count. There’s no goodreason why, if He is to be believed, He won’t

sweep His want across the anathema to set it

right.

If God is master, God can set it right but doesn’t. Such a God, the speaker insists, is not worthy of belief.

Instead of belief in God, Burroughs’s speaker finds relief in intersubjectivity, in the body and its sensations, against a religion that demands “giving up / the body to be taken holy elsewhere.” Again, this is no unambiguous redemption: the body emerges as a site of both pain and pleasure, a site of connection and risk. Intimacy, in the book’s third section, wavers between love and consumption, between the good of “unbound giving” in “Ownership, Play,” and the good of “having herself,” as in “Elegy for a Server.” What is striking in these poems, given the long conversation among women writers in which I can’t help but hear them, is what they do not suggest: no shame about sex, no angst over the religious tradition’s disciplining force. Instead, they offer an honesty about the embodied mix of joy and sorrow, self and other, knowability and unknowability. As for the agony of grief, in the penultimate poem, “I am Warm, I Know Nothing”—the very title of which suggests a positive bodily state joined to a lack of mental clarity—the speaker describes the slow forgetting of the sister’s voice, the (perhaps) fading of the initial sharp grief. There is no strong resolution here, no gift of an answer, only the twinned functions of memory and forgetting: “You see she wasn’t a dream / although time tries to make her that way.”

In the end, the collection’s negotiations with suffering neither master it nor are mastered by it; something like salvation arrives not in self-denial or mastery over another but in the joint, in the space of both self-ownership and shared pleasure. The poems themselves invite a readerly witnessing of pain but also foreclose on full clarity: while some offer up their stories in plain phrasing, others are demanding, resisting interpretation, a mix of self-exposure and enigma. As a whole, then, the collection invites its readers into an experience of its own push and pull of intimacy. Suffering emerges as both an inescapably personal phenomenon and also a site of sometimes-sharing, as in the final poem, “To Be Saved,” with its evocative but by no means conclusive description of “The signs” (of salvation?) that involve perpetual “gasping and awakening.” The poem does not give up all its mysteries, but its dominant pronoun suggests a shift: after 45 pages of “I” and “she,” this last poem’s central figure is not solitary—it’s “we.”