On Not Reading My Grandfather: The Playwright Alberto Adellach

My grandfather’s work has always loomed large in my mind, made mysterious by its inaccessibility. I never learned to speak Spanish, not fluently, not well – though I maintain the vocabulary of a toddler. Hace calor hoy. Mi color favorito es azul. The “I” centered statements of basic need, that gave rise to language.

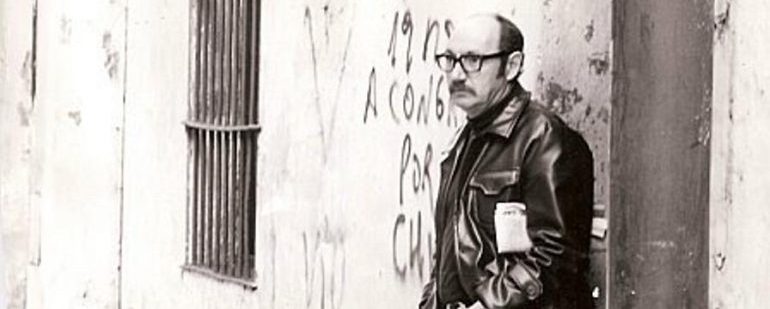

Sometimes I think it may not be an entirely bad thing to be shut out from my grandfather’s plays. I’m saved from having to make judgments about the work, and can continue taking solace in its mere existence, its proof that literature runs in the blood. All of his children were artistic in some way: my aunt a singer-songwriter, my father a journalist, my uncle a theater producer, and my cousin an actor. But Carlos Creste, who published under the name Alberto Adellach, is the one who defined himself solely as a playwright. He died when I was young, and because we didn’t share a language, I did not know him well in life. In death, I’m fascinated by his story of escape, immigration, and invention. I’m attached to the idea of my abuelo being the reason I write.

My father can’t bring himself to throw out the thousands of books in our New Jersey basement, dampening and mildewed, that my grandfather troubled to ship overseas. After the coup d’etat and subsequent Dirty War in Argentina, Alberto Adellach was blacklisted for his leftist plays, and he fled the country in 1976, soon followed by my abuela, my father, and uncle. (That year he would win two of Argentina’s most prestigious artistic awards.) Two of his older children who stayed behind were kidnapped by the junta, but survived. A playwright he’d once been close to, Griselda Gambaro, claimed that Adellach never wrote again after his children were kidnapped. Mentira. The truth is he continued to write while living in the U.S., including Romance de Tudor Place, a play about the mothers of La Plaza de Mayo. The mothers still march in front of the presidential palace every week in memory of their children who disappeared during the dictatorship, thirty thousand desaparecidos. My grandfather was dead at the time Gambaro denied him his later work, and it was my father, on his behalf, who told the playwright to go to hell.

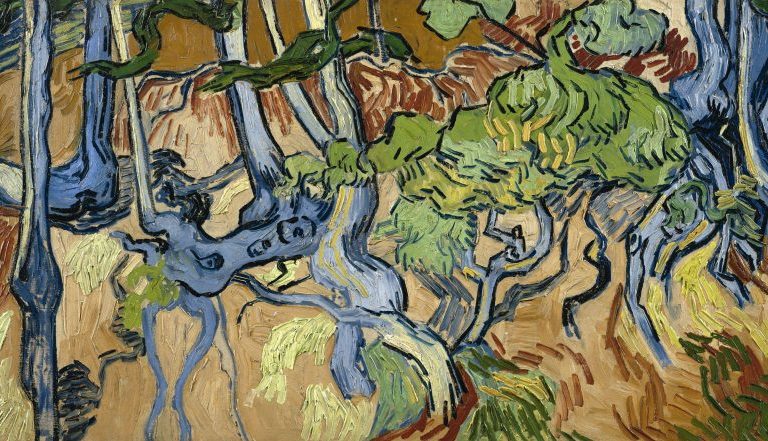

When he died in 1996 – quickly, of cancer – I was five years old and didn’t understand. Everyone was crying and I was told Abuelo passed away, an expression I’d never before encountered. So I mistook passing away for running away, and pictured him walking around the block, full of purpose, carrying a backpack of books and sweets, as I’d done on occasion. When my mother realized my confusion, she explained more explicitly that no, he had died. I like to think he might have been amused by this mistake on some level. He adored the absurd; his greatest influence was Beckett.

I know him more through the stories my father tells me than from my own memories. A favorite: when my grandfather met Allen Ginsberg. It was 1985, and the Americas Society on the Upper East Side was hosting a poetry reading at which Ginsberg and the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra read one another’s work. My father remembers Ginsberg mangled the Spanish a little, and Parra the English. After the reading, Alberto Minero, a theater critic, introduced Adellach to Ginsberg, telling him that my grandfather was an important playwright in exile. Ginsberg said he could relate because he had been thrown out of Cuba. He grabbed one of his poems and wrote a dedication to my grandfather on the spot.

My father says the funniest part of the encounter is that they looked so much the same, “exactly like what they were, after all: two Jewish intellectuals.” They were each bald, with gray beards and glasses, and dressed in white shirts and gray pants. About a year later, my father and grandfather spotted Ginsberg from a cab in the East Village. They didn’t try to grab his attention, but watched the poet walking down First Avenue, looking down as a he ambled toward Houston Street, in a manner very similar to my grandfather.

My grandfather had lost many of his original plays, having lent them to other people, and it took my father three years to track down all thirty of his works for publication in 2004. They were issued in three volumes by the National Institute of Theater in Argentina, where Adellach’s readership had faded after he moved permanently to the U.S. He would never go back to Buenos Aires. But now that his collected works are being reprinted, with the first volume already available and two others forthcoming, he’s experience something of a revival. Several theater troupes in Argentina have requested to perform his most famous play, Sabina y Lucrecia. And with the text now available online, his plays are being brought to a new audience. They have a life beyond him.

When I saw Homo Dramaticus, a collection of three short plays, staged in New York several years ago, I watched the actors transcend the limits of language. In one scene, two children’s playing evolves into a game of war and they are terrified. That existential dread is audible in any language.

I don’t know how much of himself my grandfather revealed in his plays. My poetry is about exposure, and all of the people in my life are at risk. I wonder if it’s unethical and then I keep doing it. I wonder if I would dislike having a descendant describe my motivations, as if she had insight, years later and in another tongue. I wonder and I do it anyway. Adellach’s life story is not mine to tell, perhaps it’s not even best told in my language, but it’s not entirely not mine either.