On Quietness: an Interview with Brian Morton

It wasn’t long into my semester in Brian Morton’s graduate fiction workshop at NYU when I realized that the understated manner in which he led the class was misleading. On the page, that same writer who led class so unobtrusively was one of the toughest critics I’d encountered, examining every word of a story and calling me on any false note.

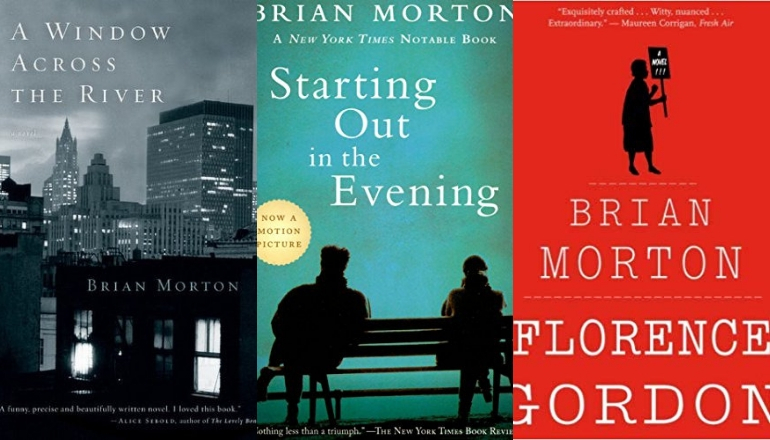

So it wasn’t a surprise to open his novels and find that same unerring attention turned on his quirky, uncertain, yet often unexpectedly larger-than-life characters. The world of Brian Morton’s novels is often studiously unheroic. His characters—some raised on tales of their parents’ generation’s stark political upheavals—tend to live out their own quieter dramas (the questions of love, of choosing to have a child, of choosing to spend one’s energy making art in an often indifferent and destructive world) in a gray-scale moral landscape. Yet for all that these struggles might be conducted in a whisper rather than a roar, they’re no less shattering. In Morton’s novel Starting out in the Evening, a character quotes philosopher Sidney Hook’s notion that “…most of the difficult decisions in life don’t involve right against wrong, but right against right. That’s why life is tragic.” In prose that gently demolishes the small falsehoods and self-justifications people use to preserve their illusions, Morton follows his doubting characters up to the edge of tragedy and sometimes beyond–sometimes so far beyond that they, and we along with them, end up at something like redemption.

Brian Morton is the author of the novels The Dylanist, A Window Across the River, Breakable You, and Starting Out in the Evening (adapted for film by Andrew Wagner, starring Frank Langella, Lauren Ambrose, and Lily Taylor), and his essays have appeared in the New York Times and elsewhere. He currently directs the MFA fiction program at Sarah Lawrence, and teaches at NYU and the Bennington Writing Seminars.

—RK: Your novels often concern writers, and over time you’ve featured very different kinds of writers. In Starting Out in the Evening, Heather, an ambitious graduate student, observes the aging novelist Leonard Schiller opening a bottle of seltzer with great care—to Heather, his considered motions model the sort of nearly-unendurable patience that’s required for the writing life. In Breakable You, in contrast, the character Adam Weller reflects: “When you unshackle yourself from a superstitious reverence for the mysterious god named Literature you can get a lot of work done.” In the writing life as you know it, where’s the balance between reverent patience and a workmanlike push toward deadlines?

—BM: Adam Weller is a creep, but the older I get, the more I aspire to the workmanlike. Nabokov said that there are three points of view from which a writer can be considered: as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter. More and more, my only goal in writing is to tell stories—tell stories and bring characters to life. If there’s enlightenment or enchantment to be had in what I write, I’ve come to believe that I can’t force it; it’ll show up or not show up on its own.

But of course, patience is still the most necessary thing. Patience, tenacity, perseverance, stubbornness, devotion—in terms of the writing life, they’re all different words for the same thing. I think the only way to keep going as a writer is to find a way to love the writing process in its every aspect: to take pleasure not only in the moments when it’s going well, but to find pleasure even in the difficulties.

—RK: Starting Out in the Evening is one of the most powerful portrayals of a writer I’ve read, and I feared the film couldn’t possibly live up to the book. Yet Frank Langella’s portrayal of Schiller felt perfect, honest, real. I wonder if you can say something about the process of having Starting Out in the Evening adapted to film.

—BM: When the filmmakers Andrew Wagner and Fred Parnes told me that they were interested in doing an adaptation of my novel Starting Out in the Evening, I was flattered and apprehensive. I was flattered for obvious reasons; I was apprehensive because I was afraid they might mess it up. For a novelist, the only adequate way to film your book would be to just…film your book, with a hand entering the picture every minute or so and turning the page.

Andrew and Fred offered to let me look at the screenplay as they were working on it, but I wanted to give them a wide berth. I knew that in order to make a good movie out of a very internal book, they’d have to make a lot of changes, and I didn’t want to be breathing down their necks. They ended up making a lot of choices that were different from those I made in the book, but I respected their choices. If someone does you the honor of doing a cover version of your song, you don’t feel cheated when they don’t sing it just the way you did.

When they told me that Frank Langella had agreed to play the main character, Leonard Schiller, I had a similar mix of emotions. I’d admired him ever since the 1970s, when I saw him in a beautiful production of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, opposite Blythe Danner. But at the same time, I couldn’t see it. Schiller is inward and self-effacing; Langella has a sort of charismatic authority. I expressed some of these misgivings to one of the filmmakers, and he said something like, “Well, you’re right. But on the other hand…Frank can act.”

When the movie was being filmed, I went to the set one day. People were setting things up when I got there—lighting people and sound people—and then I saw Langella. He was sitting alone, huddled up in a topcoat and a cap, looking at a series of index cards. I don’t know what he was doing—going over some lines, maybe, or looking over some notes about the scene. What struck me was that in the middle of all the action and movement and hurry, he’d somehow managed to create a sort of zone of stillness around himself. He radiated a sense of authority, but it was an authority of quiet. And just looking at him, I saw all I needed to know. I remember thinking, He’s got it. He’s Schiller.

—RK: In Starting Out in the Evening, Leonard Schiller writes to a young woman who has harshly critiqued him: “I once knew a literary critic who, when asked to characterize his critical ‘method’, said that he simply tried to read the hell out of a book. You’ve read the hell out of mine, and that’s all that a writer can ask.” When I read that line, I thought: that’s what Brian does with a manuscript. In many ways I’ve modeled my own teaching strategy after that—the idea of reading the hell out of a manuscript is essential to how I teach, so I thank you for that! What other strategies do you think about when you work with young writers?

–BM: Well, thank you. Your work was fun to read the hell out of. But I’m not sure that close reading is my main goal when I’m working with young writers. I think a bigger part of it is trying to help them find the psychic equipment they’ll need to keep going over the long haul. Trying to help them learn to trust their instincts. Trying to help them cultivate a spirit of resilience. Trying to help them get used to the idea that just as someone who wants to be a boxer should know that it means getting punched in the face a lot, someone who wants to be a writer should know that it means getting punched in the ego a lot. Trying to help them get used to the idea that finding your way as a writer is a process that’s likely to take a long time.

—RK: Your books often feature artists whose job is to read the hell out of the world around them… yet you also explore the personal consequences of using the raw material of life to make art. In A Window Across the River, Isaac imagines a life in which “everything he did would be documented with a merciless eye” by Nora, and he imagines her at her desk, working on “a story that would turn out to be a sort of letter bomb addressed to someone she loved.” How do you think a writer ought to approach the balance between truth-telling and protectiveness?

–BM: I think you have to be as free as possible when you’re at the keyboard, that you have to be capable of writing things that your loved ones will find offensive, things that you find offensive. You have to follow your imagination, not lead it, even if it leads you to disturbing places. But when you’re done, and you’re looking at the decision about whether to try to publish it—that’s another matter. I used to believe that Faulkner was right in saying that “The writer’s only responsibility is to his art…If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.” Now that I have kids…I’m not so sure. If I had to choose to preserve the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” or the well-being of my children…well, I’m afraid that unravish’d bride of quietness would have to go.