Belonging and Paris Stories

While the stories in Mavis Gallant’s 2002 collection don’t always center on Paris, a number of the characters have some sort of imagined relationship to the city, using it as a stand-in for their own lack of belonging.

Please note that orders placed between February 1-February 17 will not be shipped until February 17. Thank you for your patience.

While the stories in Mavis Gallant’s 2002 collection don’t always center on Paris, a number of the characters have some sort of imagined relationship to the city, using it as a stand-in for their own lack of belonging.

Jokha Alharthi’s novel is the first book by an Arab author to win the Man Booker International Prize. In it, Alharthi crafts a stunning rumination on love, responsibility, feminism, and freedom, as well as the unavoidably sour ramifications of the accompanying disappointment and betrayal.

Carson’s novel is driven by unlatching being: her protagonist’s narration progresses from the self-absorption of childhood through adolescence and into the comparative wisdom of young adulthood. Carson shows this journey primarily through changes in the way that the outside world, and those who live in it, are observed.

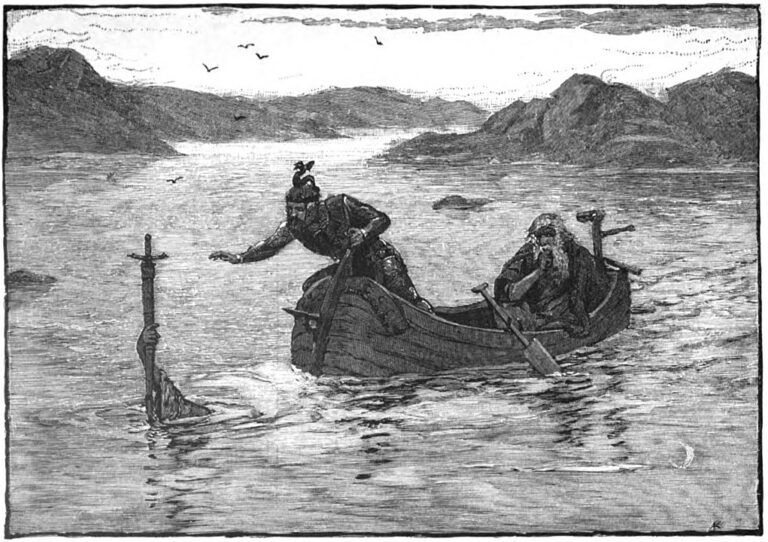

In the first book of T. H. White’s Arthurian saga, published in 1938, a young Arthur feels restless and sulky. Arthur’s stepfather shoos him away to Merlyn’s study for advice and a little cheering up, and Merlyn tells his pupil, “The best thing for being sad is to learn something.”

Over the course of Ferrante’s new essay collection, her commentary on the contingencies of telling both truth and lies shines new light on the relationship between narrative and the frightening reality she has elsewhere called the “frantumaglia.”

The challenge of Aloff’s project stands not only in relation to the mass of written material to potentially engage, but in how to remain in keeping with the Library’s undertaking “to celebrate the words that have shaped America” when dealing with an artform that creates a world “where there are no names for anything.”

When I read Laymon’s recent memoir, I had a visceral reaction. It reminded me why I started writing. It made me wonder if my writing reaches my peoples and keeps us revising and growing in our stories. If writing protects us from the silence of memories lost.

If someone were asked to discuss contemporary British masculinity, it is unlikely that they would begin with superstition and folklore, yet that is precisely the framing this topic receives in novels by Sarah Moss and John Burnside.

Vesaas’s language is rich and thickening, replete with extended metaphors that are visionary, haunting, and half-mad, recalling the ebullient, runaway brushwork of Van Gogh.

No products in the cart.