Parenthood Fear in Orange World and Other Stories and Small Animals

Most days, I push my daughter to preschool in the double stroller, next to her two-year-old brother. I try to make the commute idyllic—we look for construction vehicles or birds—but often we’re running late because someone was hungry or the school-approved shoes were not boo-tee-ful. At school, my daughter lines up with her class atop a half-flight of stairs, at the bottom of which they wait to be let into their classroom one at a time. The intention of this practice is to encourage eye contact between the teacher and child, give the teacher a chance to get a quick read on each kid’s state of mind, and give parents a chance to share any pertinent logistical information.

Most days, I push my daughter to preschool in the double stroller, next to her two-year-old brother. I try to make the commute idyllic—we look for construction vehicles or birds—but often we’re running late because someone was hungry or the school-approved shoes were not boo-tee-ful. At school, my daughter lines up with her class atop a half-flight of stairs, at the bottom of which they wait to be let into their classroom one at a time. The intention of this practice is to encourage eye contact between the teacher and child, give the teacher a chance to get a quick read on each kid’s state of mind, and give parents a chance to share any pertinent logistical information.

Upstairs, about twenty feet down the alley from the door where the four-year-olds do this lining up, is the preschool playground. The three-year-olds start their class fifteen minutes before the four-year-olds and so are already outside riding tricycles and using the tire swing when we arrive. I used to, on some warm days, leave my son strapped in the stroller and parked to the side of the playground gate so he could smile and wave at these playing children while I walked my daughter down the stairs, making sure she was last in line, before darting back up.

One day, my daughter had a particularly elaborate story she wanted to tell the teacher or the child in front of her did or she had to use the bathroom first and so, for some reason, it took longer than usual—maybe three minutes instead of one—for me to go in and come back up. When I came up the stairs, I heard frantic shouting. I ran to the stroller, stomach dropping, worried my son might have been hurt. “WHOSE BABY IS THIS?” someone was yelling. A teacher had been called over, and a crowd gathered. “I’m so sorry,” I said, vaguely and urgently as I ran to my son. He was sitting safely in his stroller. Had he been crying? No, he was happy, the teachers said. But I couldn’t leave him there, they insisted. He could have been kidnapped.

In 2011, Kim Brooks was on her way to the airport from a visit to her parents’ home in Virginia when she decided to let her four-year-old son stay in the car while she ran into Target. It was a cool March morning, and she estimates she was in the store for about five minutes. When her flight landed in Chicago, she got news that the police were looking for her. “Eventually a picture emerged of someone—a man, a woman—who had seen me run into the store, leaving Felix in the car,” Brooks writes. “That person had recorded him there, alone, and called the police. But before the police arrived, I had returned to the car. The person had watched me—us—leave. The person had waited there, explained to the police what had transpired, handed over the recording and the license plate number.”

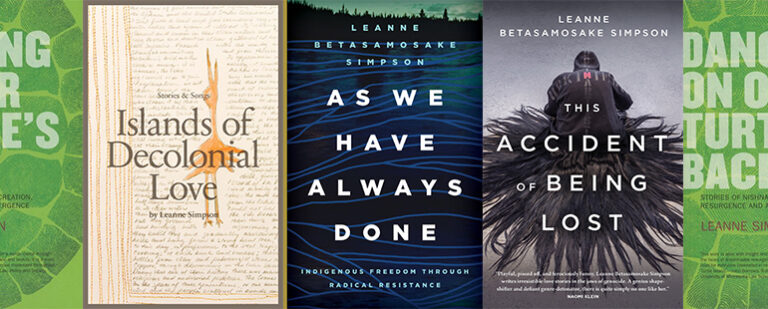

In the months that followed, Brooks was subjected to investigation, legal action, and ultimately traveled back to Virginia to turn herself in to the police. In Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear, she recalls the mix of shame, fear, and anxiety that filled those months. She also examines the ways that shame, fear, and anxiety have come to shape modern parenting.

Brooks theorizes that our notion of danger inherent to children in public spaces is relatively recent. Past generations fixated instead on moral righteousness (the Puritans) or perceived psychological normalcy (mid-century Americans). “We know that today we individually have little control over traffic deaths, gun violence, and climate change, but we can vow never to leave children unattended in cars,” Brooks writes about the current anxieties of parenting. “While fewer than three dozen children die while trapped in a hot car each year, the stories about such deaths loom large in our consciousness; preventing them feels concrete and straightforward.”

Brooks also theorizes that the current well-documented relentlessness of modern parenting is imbued with an unspoken belief that anxiety itself is a sort of insurance against disaster. “These nightmares speak to something deep inside us, our darkest fear as parents: the fear of failure, the fear that we can’t protect our children, or ourselves. But maybe this fear goes deeper than parents and children. Maybe it is what makes us suffer most as humans. Knowledge without power, foreseeing things we can’t forestall…We are living in an age of fear.”

When I was called out in the preschool alley that morning, I was sad and embarrassed and defensive. The suggestion of those around me was that I was careless with my son, that if something unimaginable should happen to him, I’d have brought it on myself. But I also felt irritated and almost smug: Simon had not been on the street, in a parking lot, in a hot car. He had been secured safely in the fresh morning air, watching other children play at a safe suburban church preschool surrounded by other parents and teachers familiar to both him and me. Parenting—living—is a constant series of tiny decisions, often involving unconscious and instantaneous risk analysis. I had decided it was better, by which I do in part mean safer (no stairs crowded with rowdy preschoolers for a still-unsteady toddler) but also more pleasant, for me and for him (something Brooks points is also valuable) to wait outside. I fantasized about going back in time and quickly responding to the admonition I’d received with a list of all the risks I don’t take with my kids. I steam their carrots and cut their grapes in half and buy organic groceries and run around manically checking for locked doors when we’re near a pool. We have baby gates at the top and bottom of our stairs. I hover more than I ought to at the openings of playground structures, and I sleep on the floors of their rooms when they have even moderate fevers. We have gone to the pediatrician for a mosquito bite. I, like every parent I know, love them so much that the thought of something terrible happening to them is too vile and wrenching to even allow.

The title story in Karen Russell’s collection Orange World and Other Stories is about that horrifying space. The story’s protagonist, Rae, is a woman who, in the midst of anxiety over prenatal screening results, makes a deal with an actual devil: she will breastfeed him in exchange for her son’s safety.

We see Rae, still pregnant but unsure if her son will survive until delivery, in a prenatal parenting class. Rae’s instructor explains to the expectant mothers that there are three worlds of parenting. “‘Orange World…is where most of us live,’” she says. She then shows the women photographs of “a smiling baby with a magenta birthmark hooping her eye. No—a burn mark. The slides jump back in time, to the irreversible error. Here is the sleepy father, holding a teapot. Orange World is a nest of tangled electrical cords and open drawers filled with steak knives. It’s a baby’s fat hand hovering over the blushing coils of a toaster oven. It’s a crib purchased used.” Green World is “a fantasy realm of soft corners and infinite attention”, and Red World is filled with “babies falling down stairwells and elevator chutes. Speared by metal and flung from passenger seats. Drowning in toilet bowls and choking on grapes.” The implication is that while Green World is lovely, the only responsible way to live is firmly enough in Orange and Red Worlds to vigilantly guard against the terrors they might bestow.

When her son is a few months old, Rae attends a new mother’s group (hilariously similar to the one I myself attended despite the surreal elements of “Orange World”) where she confides in the other women that she’s been trapped in Orange World, feeding the devil in the gutter of her house out of superstitious fear that to stop would be to endanger her miraculously healthy baby. As she’s telling the group leader, Rae expects to be met with incredulity, or at least surprise. Instead, Yvette says, “‘That fucking thing. It’s been coming south of Powell?’” Rae worries that maybe she’s being mocked, but Yvette explains: she was visited by a devil after her second child was born. “‘That thing can’t add a minute to your child’s life and it can’t take a minute away. It preys. That’s all it does. It feasts on blood.’”

Rae is torn. She has begun to suspect that perhaps the devil is not actually keeping her son alive. But, her son is alive despite the odds she was given while pregnant.

The way in which Russell grounds this mother’s group in reality with the bodily specifics of real-life early motherhood (diapers, blood clots, c-section recovery) allows the devil to serve as both a literal monster in the world of the story and a metaphor for maternal anxiety. When Rae cannot wean the devil on her own, the other mothers in the group organize an intervention. They list for her what they once believed the devil could do for them: “Stop the car from running the red light. Shrink the tumor. Jail the kidnapper. Drain the water from her brain. Return the bullets to the gun. Swat away the infected mosquito. Save the job that pays our rent. Prevent the warhead from reaching western Oregon. Keep our son safe from the police. Reverse the spread of leukemia.” After listening, Rae understands that “the interloper, it seems, arrives in a variety of costumes.” Women describe bear cubs, hawks, horses, a capybara, the largest rodent in the world.

For Brooks, it was a wolf. She recalls a recurring fear she had as a child:

I believed that a wolf lived in the back of my closet….[he] was going to eat me, though I begged him not to. He could not be reasoned with. He could not be appeased. The wolf was clever and well-spoken, and one day, amused by my pleading, he told me that if I counted to fifty before I fell asleep every night, he would stay in the closet; he would not come out…One, two, three, four, I counted every night, all the way to fifty. I never doubted or wavered in my counting. I wanted to be safe.

Brooks counts, Rae nurses. Anxious rituals of irrational insurance against the unimaginable and largely uncontrollable risk we all face. In a final confrontation before Rae finally traps and destroys her devil, one of the older mothers who’s already weaned her own interloper tells Rae: “‘You would rather this thing be the real devil than admit that you are powerless like the rest of us.’”

Brooks estimates that a child would statistically have to be left alone unsupervised for 75,000 years to be abducted by a stranger. I hadn’t weighed the risks so overtly when I left Simon watching the three-year-olds play on the preschool playground. If I had, maybe I’d have had the number ready as a response to what felt like a public shaming. But such a retort would have just been a proxy for what I felt desperate to prove: I love my son in a way that is so deep and fierce to be fundamentally at odds with the assumption that I’d be careless with him. I would breastfeed the devil. I would count again and again to appease the wolf. But I know that even if I do, I am powerless against so much.

At the end of “Orange World,” Rae calls her own mother, and they speak openly about the love between mother and child. On the phone, Rae realizes that her mother must feel the same intense, frightening, all-consuming love for her that she feels for her own son. I, too, had a moment when I realized with gratitude and awe and sadness that my mom loves me as much as I love my children. In understanding this love, I also understood the wrenching possibility of loss that runs alongside it. “Green World,” Russell writes. “Rae is learning to identify it very late in this life. Her feet push into the floorboards. Happiness travels through her, heels to skull. She cradles her son. She cradles the phone. Remotely, her mother is cradling her.” It’s not that Green World is separate from Orange World, the way it appears at the story’s beginning, but that Green and Orange are two different filters through which to see the world. Instead of being safer and by extension more loving, Orange World is drained of joy and tenderness by the anxious fear, borne of love though it may be, that defines it.