People of the Book: Bonnie Mak

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Bonnie Mak, assistant professor at the University of Illinois and author of How the Page Matters.

1. How do you define a “book”?

Liberally, and also with caution. I don’t think the definition of “book” needs to be necessarily fixed to a specific material form. But it is also the case that we might use the term “book” when we actually mean “printed codex” or “handwritten scroll”—that’s where we get into trouble. Because my research deals with particular physical instantiations of text or image, I try to use terms that more precisely describe the object under discussion.

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

I have the privilege of teaching a graduate-level course on the history of books at the University of Illinois. It’s a delight to have the opportunity to think regularly about all kinds of technologies of writing, and I enjoy the challenge of making wax tablets relevant—for instance by comparing them with iPads or mobile phones. We also talk about music manuscripts, portolan charts, scrapbooks, and blogs, and discuss how they communicate—not only with text, image, and notation, but also with their physicality. That might include the quality of their materials—whether papyrus, parchment, paper, or computational device—or their size, shape, feel, sound, and even taste and smell.

I also routinely trip over the books that I’ve piled up on the floor around my desk. That’s a kind of engagement with books, too, isn’t it?

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

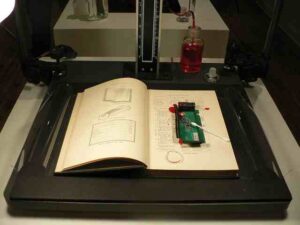

My recent exhibition with Julia Pollack called, “A Cabinet of Curiosity: The Library’s Dead Time,” allowed us to experiment with ways to make the materiality of books and e-books visible. For instance, we staged twin dissections of a codex and PDF to illustrate the space “inside” the respective pages. Because we were also interested in the social implications of that materiality, we devised a performance piece in which two librarians wore black bags over their heads as they scanned handwritten and printed materials into the computer. The spectacle was an arresting way to foreground the human costs involved in the digitization of information, whether it results in e-books or printed books, the latter of which are now frequently the product of digital technologies. We even had members of the audience join in on the performance—it was a fantastic event!

I’m looking forward to a collaboration this fall with Julia and my colleague in Art + Design, Conrad Bakker. Conrad has made replicas of paperback books that take the form of wooden blocks. We’re planning to create a circulating library of these wooden blocks, and encourage patrons to borrow the “books” and document what they do with them. The project is raises questions about the different functions of books and performances around them—obviously, these “books” aren’t books in a traditional sense, but how will our patrons treat them?

My students are also a source of creative interactions with books. Recent student projects have included a matrilineal genealogy in the form of the 14th-century Chaworth Roll; a diorama of Thomas Jefferson’s library; various experiments in book arts; and the “preservation” of digital information—that is, computer code that was printed and bound in a codex!

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

Professor Warwick Gould tells a charming story about a sandwich having been filed in an Encyclopedia Britannica under the entry, “sandwich,” at a grammar school in London. The remains of the sandwich ate away at the book over the course of years. I love that anecdote because it foregrounds the embodied nature of both the book and its reader. It also shows that the practice of reading can involve activities other than the most obvious ones.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

The fact that the book is a material, physical object, with a particular size, shape, smell, taste, and odor. It has mass; it takes up space. Embodied in a particular way, books—even digital ones—communicate to us how they should be approached and handled. Because they are material, I’m interested in how books can act as a physical interface to history. Not only are they witness to the moment at which they were produced, but also to the intervening years during which they may have been re-created alternatively as a door stop, a booster seat, a coaster, a documentary record, and a family heirloom. They carry traces of that unique trajectory through time and space, and my work is focused around decoding those traces.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

None. A shocking answer, I know! As a historian of books, libraries, and archives, I understand the value of preservation, but I don’t fetishize it. People often worry about preservation because they think that if we save everything, we’ll somehow know everything. But having more information about a particular historical event doesn’t necessarily mean that we will understand or remember it more accurately. Because my research explores the vagaries of time and maybe even exploits their effects on our cultural record, I try not to be anxious about loss. Also, my training as a medievalist has taught me that we are able to construct many different and rich stories with the most fragmentary of sources. Gaps in the record can therefore be productive, and they definitely make historical research interesting!

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

I’m not sure that anyone could have predicted the extent to which the advent of digital technologies has reinvigorated the study of books. E-books are forcing us to think hard about the role of books and reading in society. As a result, we’re developing a more nuanced understanding of the ways that the book operates in codex form, and identifying how that might be different from the “same” book in digital form. Different material forms engender different aesthetic responses. It doesn’t mean that one form is better than the other in the abstract, but just that a paperback and an e-book aren’t necessarily interchangeable in all instances. They do different things, and that’s okay. Learning to evaluate those differences is important as we revisit older technologies of communication, such as the wax tablet and papyrus or paper scroll. Those forms also serve particular purposes really well, and that’s why we’re now seeing refractions of them in new media.

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

The library, of course!

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

We’re already seeing widespread creative experimentation with the transmission of ideas. I think that such activities will continue, and continue to challenge our notions of “book” and “reading.” We already know that the codex offers a rich experience that goes beyond the transfer of word or image or notation—it transmits smells, conjures up memories, and can stand as a symbol. I’m looking forward to seeing how such aesthetic performances around the book evolve in digital environments.

Elsewhere, debates about publishing, licensing, and ownership are culminating in high-profile conflicts, viz., the Cost of Knowledge initiative that has raised awareness about the business practices of Elsevier; the resignation of the entire editorial board of a journal in protest over the author agreement of Taylor & Francis; and the court cases regarding the GoogleBooks project. These contests are about the ownership and stewardship of our collective intellectual heritage, and I think we’re all keenly invested in where the discussions go.

10. What question do you wish that I had asked related in some way to books? Ask, then answer it.

- Q: Would you share a favorite book or book-related object with us?

- A: At Harvard’s Houghton Library, there is a copy of Gilbert de la Porrée‘s “Commentary on the Pauline Epistles” (MS Typ 277) from around 1200 that carries a bookmark. This bookmark could direct attention to a particular opening of the codex, of course. But it also has a rotating disk, or volvelle; the Roman numeral on its face are used to indicate which column of the four-columned layout was of interest. The volvelle furthermore slides up and down to point to a particular line of text. This bookmark shows that in the Middle Ages there was already a sophisticated system—what might be called today—information organization and retrieval!

______

Bonnie Mak is assistant professor at the University of Illinois, with appointments in the Graduate School of Library & Information Science and the Program in Medieval Studies. She received her doctoral degree from the University of Notre Dame, where she specialized in the study of medieval manuscripts. Her research explores the production and circulation of knowledge in handwritten, printed, and digitally-encoded resources. Her book, How the Page Matters (University of Toronto Press, 2011), examined the page as a dynamic interface between designer and reader, and tracked the different materialities of a fifteenth-century text through 500 years of history and technology. She is currently working on a project that analyzes digitizations of manuscripts and printed books, and considers the role of these new resources in the broader landscape of cultural heritage.