People of the Book: Debra Di Blasi

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Debra Di Blasi, Founder and Publisher of Jaded Ibis Productions.

1. How do you define a “book”?

While a visual art student at Kansas City Art Institute in the early 1980s, I took a course in bookmaking and artists’ books. This was after I’d already studied creative writing and journalism at a state university and therefore had a narrow view of “book.” I scheduled a private tour of The Nelson-Atkins Museum’s of artist books where some of the greatest artists played with the concept of “book.” One of our tasks as art students was to be inventive, to question the “formula” for “book” as a “container” of ideas. We broke down the parts—binding, cover, page, ink, contents, size and shape—and questioned and explored their possibilities by making our own books. Once you start down that slope you inevitably arrive at the question, “Who made the old rules and why should I follow them?”

In 1998, while teaching experimental writing forms at the same art institute from which I’d graduated, I began to seriously bend the definition of “book” with the inception of The Jiri Chronicles. The 13-year “book without boundaries” project grew from one mixed media story to eventually include over 500 individual works of prose, poetry, video, audio interviews, websites, music, consumer products and, yes, physical books like The Jiri Chronicles and Other Fictions (FC2/University of Alabama Press) and two poetry collections written by the late Jiri Cech. (Cech died in 2011 when he was allegedly eaten by lions in Botswana; his body was never recovered.) Most of Jiri’s products—like his books, CDs, clothing, and perfume—are extant; others vanished into the www-dot ethersphere. The Chronicles was, I see now, my first efforts toward an experiential “book”—a serious attempt to dissolve distinctions between real life and fictive life in the same way children (used to?) play imaginary roles in a physical environment.

As a writer I’m far more interested in the creative process and its existential lessons than I am in the creative product and its commercial lessons. After all, books, regardless of format, are simply one of many means to explore the more important questions about what it means to be human. They are not, as the publishing and creative writing industries [sic] assert, the be-all end-all. The idea of “book” has more inventive possibilities when approached as a process. The process of autopoietic reiteration employed in my 20-year book project, Skin of the Sun, for example, shaped the product toward its obvious (to me) and inevitable conclusion: the human herself becomes the story, “writing and revising” solely through the internal self-reflexivity of daily living. That is, in 2014 the author, Debra Di Blasi, ceases being the writer and becomes the book.

As a publisher I’m interested in collapsing consumer-based definitions (read: limitations) of “print book” and “ebook” and “interactive book” and “experiential book.” But readers still expect and require categorization because they have not been adequately taught to define a thing based on its inherent qualities and what they mean (or fail to mean) in relation to the particular form of dissemination, whether cave painting, illuminated manuscript, paper book, ereader, interactive tablet, gallery space, or virtual space. Let’s be frank: most people are not educated enough in aesthetics[1] to ask the right questions of any narrative form or delivery system. Therefore, when Jaded Ibis markets a book, we’re tethered to industry labels in order to simplify the buying experience for readers who cannot or will not themselves bother to examine the broader meaning of a particular “book.”

One of my jobs as publisher is to understand delivery platforms, their possibilities, limitations, and cultural ramifications, and see how I and my authors and artists can use those limitations to our creative advantage. Jaded Ibis uses Print-on-Demand (POD) to publish our paper books because the system reduces upfront costs as well as our carbon footprint in an industry guilty of tremendous environmental and energy waste.

An obvious limitation of POD is that books cannot be signed for the online buyer by the author or otherwise physically altered. While at the &NOW Conference of Innovative Writing in Paris last summer, I was listening to Maya Sonnenberg present one of her stories, as the audience tried our hands at crocheting, per her request. At one point Maya held up a small crocheted square of yarn whose pattern was created from different surface heights. The swath begged to be touched, and I considered how touching the yarn was an important part of her story’s narrative, a part that could not be duplicated by just reading text—and could not be fully contemplated in relation to the text without the tactile experience. I asked myself how one could publish the “frame” of a book, using POD, wherein some pages could only be completed by the author and/or artist, and in marvelous ways. As a result, this year (2013) I hope to publish my own book “frame”, Quell the Mayhem Night, via POD. The first part of the book contains mailing labels and instructions for the buyer to ship the book to the author (me) who will complete it by hand, then ship it back to the buyer. Quell contains a page soaked in mud, a yellow feather and yellow fabric, a fingernail, original paintings and drawings, odors, a deck of cards, a DVD, a page that will significantly change as it ages… All relevant to the experimental writings contained therein and all augmenting the reader’s experience of the text, not merely illustrating it.

One of Jaded Ibis Press’s most interesting book forms is a fine art limited edition manifesting as an object that somehow reflects the literal and/or emotional ideas presented in the text. I’m thus far most pleased with Alexandra Chasin’s Brief fine art book: a large snow globe containing a miniature artist’s easel with a bastardized Andy Warhol painting on it. The “snow” was created from words cut from the novel. Tiny art history books sit on the floor around the easel, and the snow globe rests on a box containing a miniature of the paperback, printed on archival paper and buried in a pile of scraps torn from an art history book. (You’ll have to read the text to understand these aesthetic decisions.)

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

I have the good fortune to be able to remember the time, place, and emotional state I was in when I first (or many times later) read a book, no matter how many years have passed. My extensive bookshelves, therefore, exist as a warehouse of memories going back 30+ years. Many days when I’m feeling nostalgic for a world forever gone, I walk up and down the long shelves of broken spines, recalling peculiar moments from the past. Lovers and friends rise up. And quiet nights alone. And sunny patches of grass or hot rooftops on which I sprawled naked, wrestling with the literal and metaphorical weight of great tomes. And in some of those books there are notes in the margins, written by a young woman I hardly recognize: she was so certain of everything then, so passionate and guileless. Those scrawls are my only contact with her.

As I’ve begun reading more books on my Nook and iPad, I’m discovering that I still retain memories, albeit recent, that are attached to my virtual bookshelf. I can look at the tiny digital cover of a book—for example, The Best of Alan Nourse—and am immediately transported to Cape Town, where I consumed one story after another in the wee hours of the morning, hearing the South Atlantic wind rattle the windows and feeling the surf pounding the beach below… The floral pattern of the cloth draped over the bedside table, the worn brass of the old lamp, the yellow light against the white-painted closet doors, the watercolor-blue duvet cover… And waking up to the glorious morning sun of the Southern Hemisphere as it rose over Table Mountain… My husband and I finishing up the night’s reading before exiting the apartment to enter the day. There are notes and highlights in those books, too, and though they lack the evolution of my penmanship, I’m still there, in the questions I had, the ideas I found worthy.

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

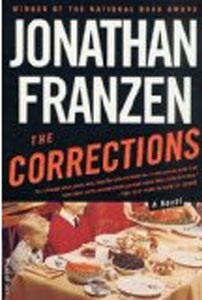

Just above my right eyelid is a small scar I got from Jonathan Franzen’s book, The Corrections. (The pun is not lost on me.) I was nervous about flying after 9/11 but had an exhibition at a gallery in Pennsylvania that October. I convinced my husband to travel with me by train. We took a sleeping car. Mark was reading Franzen’s hardback in the upper bunk when he fell asleep. Evidently, my head was hanging off the edge of the lower bunk when the book dropped from Mark’s hands. A sharp corner caught me hard, just missing my eye. There was blood.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

Palimpsests intrigue me—not so much the practical aspect of recycling paper or papyrus or tablets, but rather the political symbolism of eradicating ideas or people by writing over their words. Skin of the Sun is partially a palimpsest, eradicating and recontextualizing my “I” through material erasure and new layers. I’ve used the palimpsest method before, literally and politically, when in 1995 I tore pages from Rush Limbaugh’s blustery The Way Things Ought To Be, and used them for the ground of mixed media artworks based on bad weather (e.g., hot air, storm fronts).

When I taught an introduction to experimental writing at Kansas City Art Institute, we spent the first section on the history of the book so that students would understand what had already been attempted and what ideas could be (yes) recycled for contemporary culture. Through teaching, of course, one becomes taught. The conversations on palimpsests grew lively and wide when students recognized how many symbolic forms exist: like the McDonald’s (capitalist symbol) built near Moscow’s Red Square (communist symbol). And those gorgeous layers of political posters glued to old doors in Spain, each usurping the previous philosophies. Building an Islamic mosque over a razed Buddhist shrine. And rape as a palimpsest act of genocide.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

It depends on which form of “book,” doesn’t it? Because I travel so much, I’m interested in the blissful reality of packing hundreds of books onto a device than weighs less than a pound, rather than packing fewer than ten physical books that weigh 25 pounds into a suitcase. (My hardback edition of The Oxford History of the Classical World weighs 4.5 pounds! I can’t wait until they convert it to an ebook.)

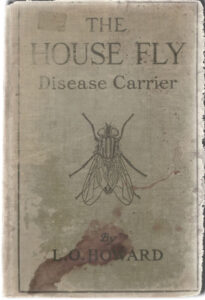

I’m also interested in the way physical books get damaged over time, which is why I like collecting very old books. The redolent scent of yellowing, mold-munched pages. The fraying fabric of the spines. The pressed flowers and (accidentally, I hope) pressed bugs. The signatures and dedications of strangers on the end papers. Or, something more startling: when I was researching “Machine Ghosts” for The Jiri Chronicles and Other Fictions, I purchased a lot of old entomology books on flies. One of them, a 1911 edition of The House Fly: Disease Carrier: An Account of Its Dangerous Activities and the Means of Destroying It, by L. O Howard, showed up with a bloodstained cover. The front endpaper was inscribed by “Edward Hogg.” I was delighted by the narrative potential in that artifact. That is something that will not—yet—happen with an ebook.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

Had to take or could only take? It would be a tragedy to lose my library and my house. That said:

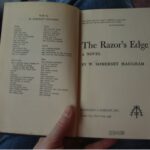

1. The Razor’s Edge, (1956 harback edition) by W. Somerset Maugham. I’ve owned this third-hand book for nearly three decades. (I bought it at an estate sale in San Francisco, and the owner had either bought it or stolen it from a library.) Every two or three years, I set aside a long, quiet weekend and reread this very same artifact.

The Razor’s Edge resonated with me early on because of the overlap of the profane and the sacred, the pursuit of the intellect and of the material, of the dilettantes who survive, the poets who die, and others who simply disappear from our lives. The novel’s deeper significance changes and unfolds as I’ve changed and evolved. I enjoy noting the new epiphanies and how the circumstances of my life have exacerbated clearer perspectives on people, religion, literature, foreign cultures and the meaning(s) of existence. Maugham was 70 when the book was published, and a man highly sophisticated and insightful, which is why I’m able to continue growing into it as I age and travel and witness and report. (There is much to be said, O haughty ignorant youth, for reading literature by people older than 35.)

2. Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle, by Nancy Spector and Neville Wakefield. I own many art books, but this is my favorite—not just because of its beauty (it is exquisite!) but also because The Cremaster Cycle is one of my favorite pieces of contemporary art. I saw the Barney exhibition when it opened at the Guggenheim in 2002, and have seen all five films. I bought three copies of the enormous (8+ lbs.) exhibition book because I knew it would be a collector’s item one day. For you bibliophile skeptics: the book’s value has increased between 600% and 1300%. Two of my copies are still unopened, so they’re probably at the upper end. If my house burned down, I might be able to eat for a few of months from the sales of those two books alone—though it would pain me to sell them for a crate of ramen noodles.

3. Unable to decide between the hundreds of other physical books, I’d take my iPad because it has the most titles on it right now. Is that cheating? Well, I don’t care.

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

I love the creative freedom of finally being able to write and otherwise make, and to publish books—my own and others—in ways about which I’ve fantasized for decades. I’m astonished by the number and quality of book projects Jaded Ibis Press receives—text + image collaborations, interactive books, multimedia and mixed media novels… Book projects like siphonophores; fantastic chimaera of many shapes, sizes and concepts… Very exciting. It’s become obvious to me that many writers have been longing to break out of the mold (double meaning intended) for quite a long time.

Some people see technology as the destruction of the book. It’s not, although it may portend the destruction of text-based narratives. (More on that later.) Technology has opened up so much creative space for writers and artists and publishers who approach the book as art instead of commodity. For me and increasingly more others, technology has resurrected The Marvelous that most of us experienced as children discovering the world and new mediums of expression and invention. Homo sapiens (and crows and chimps, et al.) make. We have always made. I suspect that we will make until that peculiar code in our DNA becomes extinct, and we evolve to extinction.

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

I find my books many places: digital download formats like Kindle and Nook; online used/collectible bookstores like Alibris; new and used bricks and mortar stores, though increasingly less frequently because my reading tastes are not well represented by them; specialized book stores like Peter Miller Books in Seattle that sells primarily architecture and design books; estate sales; and library sales.

When I need to downsize my physical library, I give my books to a shelter for homeless teens here in Seattle. They’re building up their library and I want to make certain the teens have books that may actually inform and beneficially influence their lives, rather than make them stupid with pap like Twilight.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

I’m writing a book on this, so it’s difficult to summarize in a small space. I will try, in no particular order:

- The majority does not think before leaping into technology, nor does it consider technology’s influence on the human condition. We buy it, use it, and come to rely on it in the same way radio and television became foundations of the Western information dissemination. People give technology to their children more carelessly than they give their children soda pop. Their children therefore will take new technologies for granted even more… And their children, too… And theirs…

- Scientists and engineers create because they can, and often with funding from DARPA*. They ask the enduring question, “What if…?” and then proceed to find the answer. Writers do the same. Long-term ethical considerations are not necessarily part of either club’s equation.

- *Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has one goal: to make better war:

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) was established in 1958 to prevent strategic surprise from negatively impacting U.S. national security and create strategic surprise for U.S. adversaries by maintaining the technological superiority of the U.S. military.

Until our government invests equitably in technologies driven by the humanities, we won’t veer from the increasingly narrow path we’re on.

- New technologies will have little to do with handheld devices. Google’s headgear computer, Glass, is already being tested by the public. Brain Computer Interface (BCI) and Brain Machine Brain Interface (BMBI) technologies have advanced so quickly it makes my head spin, even though I’ve been predicting its encroachment since I began studying it before 2006. They’ve begun translating dreams into images, like in the 1991 Wim Wenders film, Until the End of the World. They quickly trained a monkey (not an ape) to feed herself by thought alone. They’ve helped the blind see, the paralyzed move, and now the comatose speak. A human can control a rat’s movement by thought alone, and they’re working on similar human-human connections. The Cyborg Foundation’s mission is “to help people become cyborgs (extend their senses by applying cybernetics to the organism); defend cyborg rights and promote the use of cybernetics in the arts.” In 2014, Jaded Ibis Press and its poetry editor, Sam Witt, will publish an anthology related to these changes, titled, Devouring the Green: The Cyborg Lyric [Poetry in an Era of Catastrophic Change].

- Moore’s Law:

- How will “text” and thus “book” manifest if the human body runs/is the machine?

- Socrates speaking about the technology of writing:

And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality. —Phaedrus, Plato

Of course, I only know he said this because it is written. Nevertheless, I understand the meaning of his argument: the written word has not ended war or rape, or stopped us from destroying the environment that sustains us. I don’t think that we’re better creatures and, in fact, may be worse, as we’ve lost our connection with nature and our delicate place in it.

- The future book will use gaming technologies designed for Real-Time Interactive Simulation, BMBI, and 360-degree, 3D virtual headsets, like Oculus Rift, to create narratives that require the same or higher levels of intellectual, conceptual and knowledge-based input that a text-only book does now. These will not be passive experiences; they will be highly active, using multiple input from the “reader’s” own brainwaves and neurological pathways. The better the reader is at self-reflexivity, pattern-making, and creative thinking, the more emotionally and intellectually rewarding the play.

- If Homo sapiens survive our current idiocy, a future post-text/post-literate world (i.e., the return to the oral tradition, augmented by “telepathy” and multi-sensory experiences through machines) may be the only way humans will really understand and perhaps feel genuine compassion for each other and our place on this planet.

- Everyone will become extinct in their own lifetime. Everyone will die.

- What is the purpose of books? Ultimately: what is the purpose? This question should be, must be asked by every literature and creative writing department in the world, and by every publisher, and by every writer, reader and listener. Otherwise, you remain the progeny and progenitor of the beast that may envision its better self but never achieve it.

10. What question do you wish that I had asked related in some way to books? Ask, then answer it.

- Q: Do you get tired of defining “book” in a world where 50 Shades of Grey was the fastest-selling paperback ever?

- A: Yes. Yes, I do.

______

[1]How many writers today attend the opera, symphony, and theatre and understand the vital physiological differences between a live experience and a simulacrum? How many writers regularly visit art and science museums, explore great architecture and urban design, read far more than literature and literary theory? How many can comfortably discuss ideas inherent in all such artworks and subjects, and their interrelationships, and those in relationship to the planet’s biospheres and the greater cosmos? Critically, how many writers are aware that specialization (narrowing input) in any field reduces exogenous influences and thus stagnates neurological synaptic plasticity. In other words, you don’t gain—or may even lose—the ability to build patterns from and relationships between divergent information if you narrow your focus to one field of study.

______

Debra Di Blasi is founding publisher of the multimedia company, Jaded Ibis Productions and its publishing imprint Jaded Ibis Press. She frequently lectures on the intersection of literature and new technologies, including exploring the boundaries and inventing new forms of “book.” She is the author of 6+ books, including the novellas, Drought & Say What You Like; multimedia books, Gorgeous: The Fabulous Plastic Surgery of Dr. Harold W. George and Skin of the Sun: 5 iterations toward human as novel; and the multigenre/multimedia book project, The Jirí Chronicles. She is recipient of a James C. McCormick Fellowship in Fiction from the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, Thorpe Menn Book Award, DIAGRAM Innovative Fiction Award, and a Cinovation Screenwriting Award, among others. Her fiction is included in a many leading anthologies of innovative writing and has been adapted to film, radio, theatre, and audio CD in the U.S. and abroad.