People of the Book: Whitney Trettien

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Whitney Trettien, Ph.D. candidate at Duke University, who schemes on a variety of projects related to old books and new media.

1. How do you define a “book”?

In ordinary use, ‘book’ for me means ‘codex,’ a physical form in which a stack of relatively flat material is bound along one edge, and can be opened or closed. It’s a media platform. ‘E-book’, then, is a bit of a misnomer: the electronic tablet is the platform, delivering long-form (that is, “book-length”) content.

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

In my research, I spend a lot of time examining books as artifacts, studying their binding, their paper, how they’re put together, looking for traces of readers’ interactions. Museums and even to some extent reading rooms have taught us to gaze upon old books as time capsules physically embodying the past—so when we hover over the glass-encased Beowulf manuscript in the gallery at the British Library, we marvel at how old it is, and what that age signifies within the history of English literature.

In my work, I try to hold this inherited interpretive framework in abeyance in order to see the accreted remnants of all moments in a book’s existence. Thus the Beowulf manuscript contains not only a text scratched on vellum near the end of the tenth century, but also the sixteenth-century ownership mark of Laurence Nowell, damage from a fire in 1731, paper frames added in 1845, and two sets of foliation marks—all of which it shares with the three other manuscripts that it was bound with in the seventeenth century. Although we tend to think of old books as enabling time travel—literally putting us in touch with a distant past—they are in fact palimpsests that condense, remediate and reconfigure history. More than reading books, I’m interested in excavating bibliographic evidence of how various owners, authors, readers, and institutions, at multiple points in time, saw themselves in relation to their inherited past and an imagined future.

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

My most unusual interaction is probably also my most mundane: I use them as furniture. My coffee table is four stacks of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books—a lovely set, each cover similar in design but differently colored—topped with an old printer’s lettercase salvaged from a warehouse full of antique junk. The Story of Civilization makes a lovely window seat topped with plants; several Funk and Wagnalls are a sturdy endtable. Old dictionary bindings frame woodcuts from The Faerie Queene and cover light sockets. Pages that fell out of a paperback copy of Flannery O’Connor’s The Violent Bear It Away shade the bulbs in my chandelier. When I first moved to Durham, I had 28 boxes of books and no furniture; I had to get creative.

I’ve since started using books for art projects, too—like a tree stump sculpture that I built during a residency at Elsewhere in Greensboro, NC.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

I love moveable parts in books. The history of early European printing is full of these paper mechanisms. Nested discs called volvelles were used as calendars and astrolabes for calculating dates and the position of the stars; in one particularly fascinating example, the baroque poet Georg Philipp Harsdörffer created what he called the Fünffacher Denckring der Teutschen Sprache, or Five-fold Thoughtring of the German Language, a kind of generative dictionary made from five nested paper wheels, each inscribed with a syllable. Turning the discs constructed new words by combining syllables.

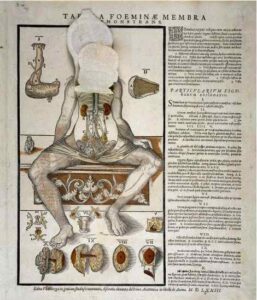

In the sixteenth century, Vesalius, considered the founder of modern human anatomy, instructed readers to cut out his printed images of the human body and reassemble them in order to learn how the different parts fit together. His pedagogical use of cut-outs blossomed into the genre of flap anatomies, printed broadsheets showing the human form pasted with printed organs—the kidneys, the uterus, the lungs. Readers (users?) could lift these delicate paper organs in succession, performing a kind of “live” dissection on the body.

Moving parts had other uses, too. In a 1570 vernacular edition of Euclid’s Elements we find pasted-down flaps that allowed the reader to transform a flat printed square into a three-dimensional pyramid, thereby teaching geometric principles through interaction. Eighteenth-century flapbooks were used to instill gender identities in children; Jacquiline Reid-Walsh has been studying these marvelous artifacts and has secured a grant to build a digital archive of them. Other flaps were used to conceal portraits, inviting readers to engage in a playful revealing and concealing of authorial identity.

Although these examples seem unusual, moving parts are far more prevalent in early printed books than we might think. In fact, there’s much to be learned about the history of printing and binding by studying them. Early books are not just pages of linear text; they’re assemblages of paper technologies, designed to embody and produce different material relationships between a reader and an idea.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

Recently, the fore-edge, opposite the spine. The fore-edge is our entrance into the book, where our thumbs first dig in and pull open the covers; it leads us to a world of surfaces that compose the book’s pages. Yet it’s also where the codex makes visible its own depth, showing us the third dimension of paper. In other words, the fore-edge is where paper becomes a page, and pages turn back into paper—that magical transformation upon which the technology of the book depends.

The fore-edge has also been the site of designs both functional and aesthetic. Before we began shelving printed books vertically and spine out, they were often stacked flat and spine back; as a result, some early book owners wrote the title on the book’s fore-edge for easy filing. Fore-edges have also been gilded, gauffered, and painted with designs, sometimes in such a way that the image is only revealed upon opening the book.

A particularly lovely seventeenth-century example of fore-edge painting is a Bible and Book of Common Prayer at Houghton Library. Although the closed edge is gilded, when opened, the gentle slope of the book’s large, folio-size pages reveal King Charles II, staring at you while you read. He disappears again behind gilt as the book closes.

The practice of painting the fore-edge in this way reached new heights in the nineteenth century, when misty romantic landscapes became popular. The Boston Public Library has digitized its sizable collection; browsing it online gives one a good sense of how detailed these small paintings can be. Some books even feature a double painting, such that different images appear and disappear depending on which direction the pages are fanned. This charming art lives on today in the work of Martin Frost, whose exquisite figures almost seem to shimmy with the movement of the pages.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

I’m really not sure I would take any! That isn’t to say they aren’t precious to me. The annotations in my copies of Chaucer, Wittgenstein, Calvino or Woolf would be missed, though not for their content so much as their concretization of hard-fought Knowledge. My small but growing collection of pop-ups is dear to me, as are a few beautiful nineteenth-century children’s books I’ve picked up over the years, mostly chromolithographs (my favorite form of book illustration).

And of course there are a handful of books owned for sentimental value, like a copy of Gustave Dore’s illustrated edition of Dante’s Inferno, once owned by my Great-Great Aunt Helen, a schoolteacher who scandalously rode a big-wheel bike. Strange, I know, that someone so enamored of the materiality of books wouldn’t miss any of her own if they were lost in a fire—but true. Most books can be replaced, and thankfully sentiment doesn’t burn as easily as paper.

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

Our current era of mass digitization is radically reconfiguring the relationship between past and present. Photographs of old or rare books show them frozen in time by endlessly reproducing and repeating a single moment—the moment when the book was photographed. At the same time, the physical object (in most cases) continues to exist in a library somewhere, accreting history, aging. Add to this Dorian Gray-ish scenario the fact that photographs of a single copy represent an entire edition, which itself may exist in variant copies, and the significance of this transformation for research begins to become clear.

We’re living in a moment that loves the idiosyncrasy of bibliographic oddities, from annotated copies and Sammelbände to books that have been cut-up or otherwise bear evidence of readerly manipulation. Yet it’s also a moment of reproducibility, in which pages once viewed in person by a privileged few are accessible to a wide audience in both facsimile and plain text form. Thus a digitized copy of the Geneva Bible—a copy that is no doubt itself variant in some way—becomes “the Geneva Bible”; a digitized nineteenth-century edition of King Lear becomes, through Project Gutenberg, simply “King Lear,” its dense editorial history eradicated under the banner of open access.

Book historians and librarians are acutely aware of this tension. Mitch Fraas recently tweeted two very different looking pages from two photographed books of the same edition in order to highlight why we need multiple digitized copies. This kind of historical knowledge—the realm of book historians and librarians—is needed now more than ever, and should be part of the conversation about digitization practices.

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

I gravitate to those places that are “find and give away”—where our media detritus is sucked up and spit back at us in all its ugly, ephemeral glory.

In Maryland, near where I grew up, there’s a used bookstore (and record shop, and video rental) called Wonderbooks. It’s the kind of place that specializes in old sheet music, Christmas albums, and the odd assortment of Desktop Physicians. As a kid, I would comb its tall, disorderly stacks for cheap and curious bits of literature and poetry—inevitably in the form of a decades-old Penguin paperback, its binding glue so dry that the book would start flaking pages halfway through reading it.

This desperate, greedy bid for knowledge wouldn’t have been possible without Wonderbooks’ indiscriminate BUY/SELL/TRADE policy. We tend to think of libraries as the storehouse of our cultural memory, but they don’t store the past so much as package and present it in a way that channels our vision of the future. Places like Wonderbooks, though, offer a much broader glimpse of our history, shoring up all the detritus excised from our more venerated institutions.

I’ve also found many of my favorite books in dumpsters. When working in a public library, I learned just how many discarded books are tossed in the bins out back—especially books of the kind I collect, old dictionaries and encyclopedia sets. Ever in search of more shelf space, public libraries are shedding their reference works like dead skin, replacing them with computers and database subscriptions. Their loss is my gain; I love these extinct dinosaurs, with their faux leather covers and absurd claims to a “universal” or “total” printing of language and knowledge. (Websters and Encyclopedia Britannica played an important role in furnishing middle class homes, displaying upwardly mobile aspirations toward erudition through their sheer, shelf-sagging enormity.)

I’m not sad these books are being replaced by more efficient, up-to-date electronic reference works; but I do like to save the ones I find. A kind of secondary “dumpster” where I find books are the bins labeled “FREE” that dot the halls of universities. A decent living might be made as a kind of modern day rag-and-bone man, repurposing and reselling abandoned books found at the fringes of libraries and colleges—only instead of saving old rags to be made into paper for books, you’d be saving old books from destruction in the face of digital databases.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

There was a time when I thought a more experimental brand of highly-designed digital books might emerge—books in which design bore some of the weight of the text’s argument. That thought has evaporated, though. Digital publishing formats are becoming (perhaps already are) calcified, even more so than those of printed books, and I don’t see many interesting developments in that vein (the occasional iPad “pop-up” book aside).

A renewed interest in the materiality of the codex is generating some of the most experiments experiments in hybrid print/digital publishing. I’m thinking of Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse’s Between Page and Screen, in which the book is read by holding printed codes before a webcam, as well as Caitlin Fisher’s recent augmented reality art. If networked digital culture continues to dissolve into everyday objects—into a pair of glasses, or the heel of a shoe—then we may begin to see more printed digital books, which are read the “old-fashioned” way but experienced as something wholly different. I hope so, anyway. Reading an augmented reality printed paper e-book seems to me a far richer experience than tapping through videos embedded in longform text on an iPad.

10. What question do you wish that I had asked related in some way to books? Ask, then answer it.

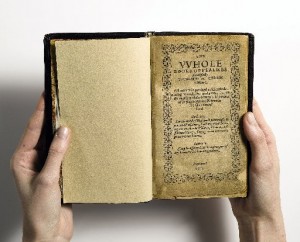

Q: A copy of the Bay Psalm Book recently sold for a record $14.2 million. Why spend that much on a book that is available to all in digital form?

A: The Bay Psalm Book is a perfect example of what I described earlier as our relationship to old books as time capsules of the past. It’s certainly not the rarest book one could own; eleven copies of its first edition are extant—a small number, to be sure, but hardly the smallest. (Isabella Whitney’s A sweet Nosgay (1573), considered the first secular book of original English verse written by a woman, exists in a single incomplete copy.) Nor is the Bay Psalm Book the most beautiful printed book, even by a loose definition of that very subjective adjective. Rather its value lies in its being the first book printed in America, in a culture obsessed with firsts (itself a function of our linear, progressive conception of time). To own it is to own—in a very real way—a “piece of history.”

Given that, it makes sense that digital facsimiles couldn’t substitute for the object itself. Photographs on a screen show us the content of an artifact, but don’t put us in touch with it. Of course, now that they’re circulating, these digital images add one more layer to the dense historical, cultural, and material palimpsest that we call “the Bay Psalm Book,” reproducing and distributing it in a way that subtly transforms our experience of the $14.2 million object. In the perceived gap between these mutually constitutive mediations—the single, jaw-droppingly expensive book and the worthless excess of its digital reproductions—is the state of the book right now.

______

Whitney Trettien is a PhD candidate in Duke University, finishing up a dissertation on the Little Gidding Harmonies, a set of seventeenth-century cut-and-paste biblical concordances. She schemes on a variety of projects related to old books and new media. Visit her online at: http://whitneyannetrettien.com.