Plenty of Pride & No Prejudice?

A while ago, while browsing the local Barnes & Noble, a friend and I started discussing how we got into LGBTQ literature, and how much reading specifically queer authors had meant to us in times of turmoil, both personal and not. This was in the aftermath of the Orlando massacre, when we both turned to books to find respite from the persistent trauma and terror. I kept poems in my pocket to read like mantras, I lost myself in novels so as to forget for a short while the overwhelming reality, I also read memoirs and essays that spoke of hard-won experience, of grief and joy.

Delving into those stories and testimonies had us realize that this process served two main purposes. First, a form of reassurance: the need to know that one is not alone, however isolated one might be. Second, it’s about acquiring knowledge—about the multifaceted cultures and histories of a community that has always been around, and that has also always been fundamental to the broader history of humanity. But the various ways in which we relate to queer literature can reveal the complexity of our engagement with queer identities, beyond the question of how useful and valid the specific “LGBTQ literature” label is—how it can contribute in preventing certain parts of literature from reaching a broader audience while guaranteeing visibility for certain issues and people.

This led to a very serious and formal survey among a definitely representative sample of the queer population (i.e., a bunch of my friends to whom I sent a volley of texts), to find out what kind of literature had accompanied us during our self-discovery process. Plenty had scoured, precisely, that LGBT shelf wherever it popped up in any library or bookstore, so as to read as much as they could, taking the good, the bad, and the mediocre; others hadn’t been able to do that at first because it would have meant jeopardizing the relative safety of the closet, so they’d spent years reading on the sly books borrowed from trusted friends, and had flocked to the shelf as soon as they could.

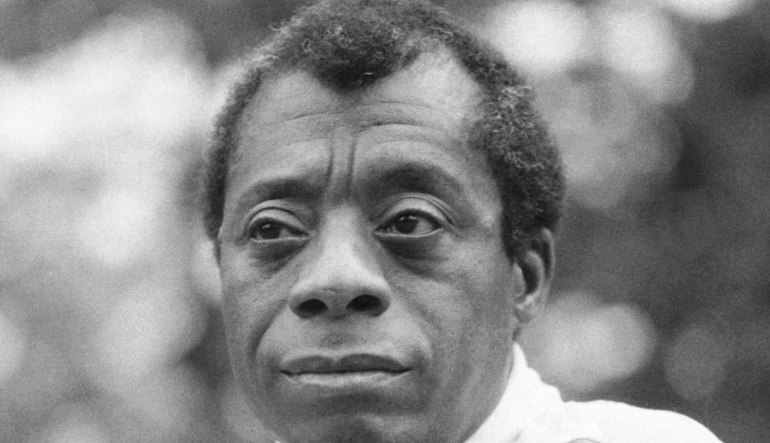

We devoured the “classics”—Baldwin, Lorde, Woolf, Maupin, Winterson, to name a few—and binged on any new title we could hear about. All around, just like Alison Bechdel’s alter-ego in her memoir Fun Home, many of us have either been hit with the big realization and/or taken their first steps as baby gays through literature, and most often, reading queer authors feels revolutionary, liberating, and most of all, it brings joy, even when the characters’ fates lack a happy ending. Because here’s a vast literary field that’s radical in its very existence, interrogating as it does the norms of social life, renewing the bond between the personal and the political. Here’s literature where, at least within its pages, we readers can feel relief and pride.

And yet it’s also necessary to acknowledge how forms of prejudice are still ingrained within that very field, even when we assume or hope that its foundational message of inclusivity might help do away with any kind of marginalization. What does it mean that female queerness is still largely rendered invisible throughout history? How do queer writers of color navigate racism both outside and within the queer community? Are opportunities for queer writers truly available and accessible to everyone? Being queer doesn’t magically prevent anyone from being bigoted, and reading one’s way through queerness also means thinking critically about how queer authors themselves engage with harmful ideologies.

There’s additionally the ever-thorny question of the market. Capitalism loves the shiny co-opting potential of queerness, the politics of which are always torn between assimilation and resistance. In that context, even within the queer community, certain voices emerge as more bankable than others: they sell more, either because of some fabricated shock-value or because they conform just enough to be reassuring to mainstream (straight) readers. We are still seeing it today, as the voices and stories of some of the most important members of our communities are still being distorted or silenced: mainstream retellings, sanitized and whitewashed as they are, would have us believe that Stonewall wasn’t led by trans women of color or that it wasn’t a riot against police forces.

Of course, the landscape of queer literature is a changing one, and that’s what makes it so exciting. Whether they write poetry or novels, essays or YA fiction, many contemporary queer authors today are seeking to reclaim their stories and the stories of those like them, to resist truncation, to be, in short, fully seen. Think Gabby Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath, which examines feminism and female queerness from a Latinx perspective; think Danez Smith and Saeed Jones, who articulate the intricacies of black queer masculinity; think Natalie Diaz, who sings of queer desire and Native existence in the same breath. Seeing them around as powerful examples of just what queerness can do with words if it can resist all erasure and normativity, reading these authors in-depth inevitably leads to those who paved the way.

All in all, what transpires most throughout is how vital reading about our history, both past and current, has been to many among us. We need a way to connect to our shared past in order to envision any possibility of a future, and literature provides this continuity. It is riddled with lacunas for sure, but still, it holds the promise of belonging. But the knowledge of this history requires us to be aware of the causes of silence, which can come from both outside and within the community. Queer literature is the source of continuous pride, as it attests to the enduring strength and resilience of our people—we can’t let it succumb to the very prejudices we struggle against.