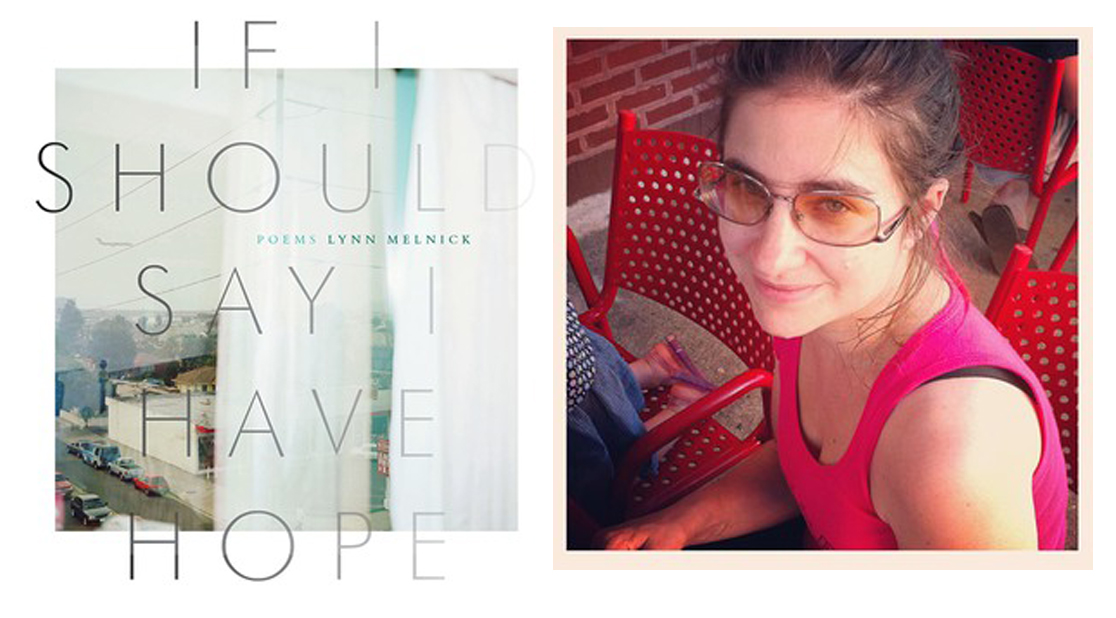

Poet Activist Spotlight: Lynn Melnick

Given that the presidential election was just won by a candidate who’s bragged about his ability to grab women’s pussies (paired with the perpetual and tiring accumulation of misogynistic remarks about my body that I have dealt with as an almost thirty-year-old woman), I could not be more grateful for an excuse to escape into rereading If I Should Say I Have Hope. Situated in another of time, I might write praising the wondrous lyricality in Melnick’s poems, how lush her language is, how slick her line breaks are, how skillfully strange and disorienting her images can be. But I am very concerned about the body, about the safety and rights of women, about how flimsy and uncertain progress is. And Lynn writes the body in a way that challenges the destructive weight of the male gaze, says “I don’t want a body, not with what’s inside.” Says, “There are so many ways / for a body to yield monstrous.” She carves out a space for hope amid the onslaught “taintless light / and heinous yes,” of “sloppy beauty,” of trying on “mediocre hot pants /at the thrift store.” I am very grateful for her insistence upon hope against a landscape that is in many ways predatory toward women, and I am grateful for all the work she does within the literary community to create spaces for women to feel worthy and seen.

Lynn Melnick is the author of If I Should Say I Have Hope (YesYes Books, 2012) and the co-editor, with Brett Fletcher Lauer, of Please Excuse This Poem (Viking, 2015). Her second poetry collection, Landscape with Sex and Violence, is forthcoming form YesYes Books in fall 2017, and her poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The Offing, The Paris Review, Prairie Schooner, and A Public Space. She teaches poetry at the 92Y in New York and is the social media outreach director for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, a nonprofit organization that aims to create transparency over the lack of gender parity in the literary landscape and to amplify historically marginalized voices.

Stevie Edwards: How does activism show up in your poetry (and, perhaps, how does poetry show up in your activism)?

Lynn Melnick: Hmm, I guess poetry shows up in my activism because poetry is always with me. (I know I’m corny. But it’s true!)

I write about sex work, and rape, and abortion, and street harassment, and intimate partner violence, so I feel like every time I get one of my poems published it’s a little victory not just for my own poetry career but for naming and talking about the things I name and talk about.

But, as far as when I sit down to write, I don’t seek to make a particular political, social or any kind of point. I’m just writing what I know and what consumes me. I’m glad that the work is (sometimes) successful as both art and activism, in its way.

SE: As a “social media”(but not yet “real world”) friend, I have long admired your voice as a necessary subversive force in the literary world, particularly as an advocate on behalf of women writers. Are there other writers (or artists/humans/etc.) who have inspired you to take such an active role?

LM: Wow, thank you for saying such nice things!!

One of my first poetry loves (and still to this day) was Alice Walker and she is certainly a writer for whom the act of writing is right alongside the work of activism. She is brilliant and necessary at both, and certainly inspired me to do what I do.

I am lucky to work beside so many amazing women at VIDA: Women in Literary Arts. We work really hard and really passionately (fighting patriarchy from within patriarchy is not easy!) and I am consistently impressed with their dedication and intelligence – and they are kick-ass writers, all! Amy King and Camille Rankine have been special inspirations to me. We have been through the trenches together this past year, and I have seen their toughness and their compassion and, holy shit! The lit world doesn’t even know how lucky they are to have these two women, both for their poetry and their activism.

SE: I’m going to pose a hypothetical question that’s been posed to me at various times because I’d love to hear your answer to it. Let’s say I am an editor who has inherited (or maybe created) a journal that has historically published predominately white men of a certain socioeconomic class. I would like to move toward a goal of publishing a more diverse array of voices, but for some reason my submission pool is not very diverse. What do you think I should do?

LM: That’s an interesting question! We have a lot of tips on our VIDA website here, including ideas for editors specifically to create a more balanced (and interesting!) TOC.

If I inherited (or had started) this hypothetical journal you describe, I would put a note on my home page or in the journal itself acknowledging past failures and pledging to change. And then I would! I would start to read widely, I would seek out new and diverse writers by reading journals with a proven commitment to diversity, I would look on bookstore shelves, I would keep an eye on local reading series’ and at conferences like AWP – and then I would solicit those writers. A lot of times writers don’t send to certain journals because they don’t feel welcome. Make them welcome by soliciting and make them welcome by publishing a range of voices.

So many editors pretend that their hands are tied because of who is submitting work to them, but that’s bullshit, not only because they could also solicit, but they already do solicit. They just mostly solicit white men. If their hands are tied, they have tied them all on their own. The New York Review of Books is almost all solicited content, for example, and their TOCs are among the least diverse so they are actively not looking for a diverse TOC. If I inherited a journal like that I would work my ass off to change the white male supremacy of its pages – and change of that nature is not difficult, though it does take awareness and desire.

SE: Where did you get the impetus for compiling Please Excuse This Poem: 100 New Poets for the Next Generation (Viking, 2015)? What were some of your goals with curating its contents?

LM: My co-editor, Brett Fletcher Lauer, and I had had many conversations over the many years of our friendship about how poetry saved us in one way or another when we were variously troubled teenagers. So putting together an anthology of contemporary poems edited with teenagers in mind, and published for a YA audience, was almost the next logical step! Our goal was to create an anthology that would speak in some way to our younger selves, and to include poems and poets in there that reflect the world we live in and the people in it. So, really that was our biggest goal— to make young people see that poetry is a relevant necessary thing and to change lives the way poetry once changed ours.

A lovely bonus has been how colleges have also adopted this book in their classrooms, and I think one of the reasons they have is that the book is so contemporary and so diverse, and many of the available anthologies were not quite so. I just love that we were able to bring so many poets and poems to people who might not otherwise have known about them. I love that we got to change who and what people think of when they think of poetry.

SE: Over the past few years, there have been a number of serious accusations involving sexual predators within the literary community. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on what we (as a community) can do to empower writers to speak up in such situations?

LM: The lit world is no different from the world world. We can talk all we want to about believing the victims, but when people speak up or when predators are exposed, it’s like no one wants to deal. And so many so-called progressives – who make careers out of referring to themselves as badass feminists and such – really don’t want to jeopardize those careers by rocking any boats, god forbid, the horror. Because, you know, which is more important, book sales or community safety?

This has been a difficult question for me to answer because I’m so angry with our community for its failures. That said, I do think the next generation of writers isn’t so entrenched in patriarchy (or I hope, anyway), and slowly women will be more empowered to report crimes or otherwise speak up and not worry about retribution or other fallout. I want to encourage everyone to check out the VIDA Review’s “Reports from the Field” column, especially the pieces on sexual predators in our community, in order to understand what many women go through and to hopefully feel safer and more empowered to tell their stories. I want the column to be a place where women can feel safe to speak up, but I also know, from both personal experience and from my work with VIDA, how dangerous and difficult that can be.

SE: What other projects are you working on right now? I feel like I see your name everywhere doing a million things.

LM: Oh gosh, do you? I hope I’ve not grown tedious!

You’ve caught me at a strange moment because I’ve just (like just) turned in my final manuscript draft for Landscape with Sex and Violence to YesYes Books and I feel a bit adrift. Because I want to do all the things and none of the things. Lately, I’m very interested in what it means to be a middle-aged woman in this culture and in this body and I’ve sort of been exploring that in poems and also trying to reconcile my early life with my life now. It’s scary to start over with poems, post-book, and yet really freeing and fun.

But I also have a novel that needs to be overhauled and I also am working on a possible project for younger readers, so I guess I’ll see where I am most compelled to direct my attention next . . .