Reading Deesha Philyaw’s “Peach Cobbler”

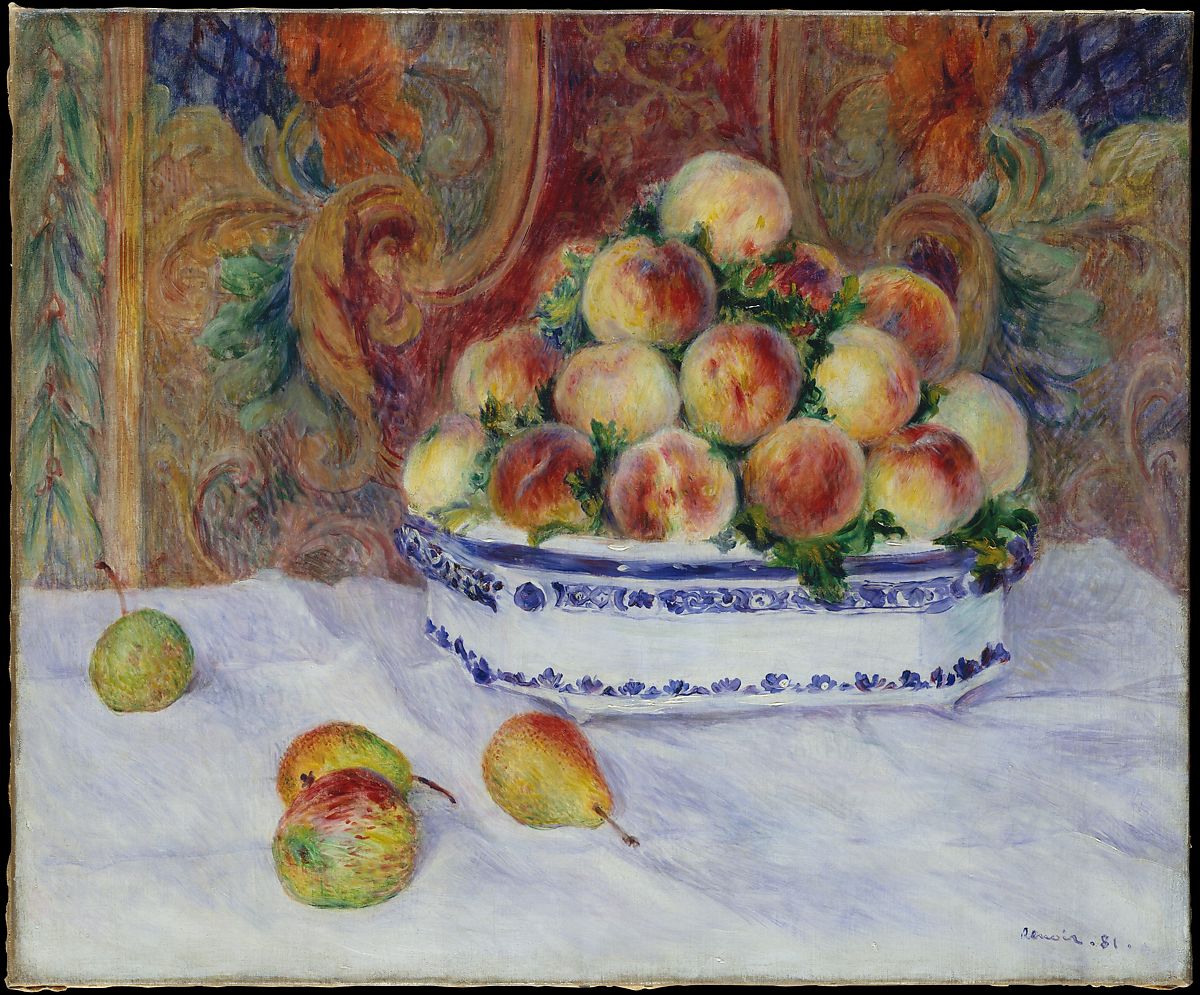

“Peach Cobbler,” the centerpiece of Deesha Philyaw’s award-winning 2020 collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, is a wonderful coming-of-age narrative. The story is told from the first-person perspective by a Black girl named Olivia, and it moves quickly through her childhood, from when Olivia is five to when she is a junior in high school. Philyaw manages this long stretch of time by tracking an object—a peach cobbler—and how the narrator’s relationship to that object changes over the years. The arc that develops serves to underscore the narrative arc of the story. And by writing so sensually about food, Philyaw draws the reader into the story: we are there with Olivia, smelling the peaches and the sugar and the cinnamon, as she develops from a girl into a woman.

At the start of the story Olivia is very young, but she carefully watches her mother make a peach cobbler every Monday. “When I was five, I hovered around my mother in the kitchen,” she says, “watching, close enough to have memorized all the ingredients and steps by the time I was six.” Her mother does not have the recipe written down, so Olivia can learn only by observation. We quickly learn that her mother is not an everyday cook—TV dinners are often served for dinner—so the cobbler is a special, weekly event. And then we learn that the cobbler is made for the local pastor, who, after eating all of the dessert right from the eight-by-eight baking pan, disappears into the bedroom with Olivia’s mother.

Philyaw wonderfully complicates our assumptions around food, motherhood, and religion right from the start. We might originally anticipate that this time together in the kitchen is one that brings the mother and daughter together. Instead, the narrator says that she “learned never to ask questions about that cobbler,” just as she was never to ask questions about the pastor, who she originally conflates with God. This lovely, sweet dessert is not being made for Olivia and, in fact, if the pastor does not appear, the entire dessert is thrown into the trash.

Later, Olivia overhears a conversation between the pastor and her mother, her mother explaining why she is not allowing Olivia to attend a friend’s party: “They can raise their child however they see fit. But I’m not going to raise mine to go through life expecting it to be sweet, when for her, it ain’t going to be. The sooner she learns to accept what is and what ain’t, the better. She get a taste of that sweetness, she’s going to want it so bad, she’ll grow up and settle for crumbs of it.” Olivia’s mother is speaking about expectations and desire, but the language she uses (“that sweetness,” “the crumbs”) braids these emotions together with the peach cobbler, so that we can see how the cobbler becomes an objective correlative in this story, holding complicated emotions and meanings that shift as the story progresses.

The distance that grows between mother and daughter is heartbreaking. Olivia is desperate for her mother’s attention and love: “maybe if I watched her hands as she sliced the peaches, counted how many times she stirred, and learned to gauge by smell the exact moment to take the cobbler from the oven—maybe I could make a cobbler that pleased God. And maybe that would please my mother.” The cobbler—a comfort food, if there ever was one—is providing comfort only to the pastor, but as that is all Olivia sees, she can only mimic what her mother is doing. The hunger that Olivia has for her mother’s approval and love is made tangible by her desire for the cobbler.

Late one Monday night, when she is eight and the pastor did not arrive, Olivia returns to the kitchen and begins eating the cobbler that has been thrown in the trash: “In the darkness, I reached down into the garbage can until my fingertips were wet and sticky. I grabbed a handful of the cobbler and shoved it all in my mouth at once. The sugary juice dribbled over the corner of my mouth down to my chin as I chewed. I savored the peaches and the soft bits of crust soaked through with the syrup. Nothing had ever tasted so good.” Olivia’s raw hunger is made apparent here, and the consumption is all the more fulfilling, for both Olivia and for the reader, because up until now, only the pastor has eaten the cobbler. (Her mother, pointedly, never eats it—she says she doesn’t like peaches.) There is a feral, almost sexual quality to the way that Olivia eats the dessert. Again, Philyaw plays with our expectations and assumptions—the cobbler is not the homey, comfort food that we know. For Olivia, it is a representation of what she cannot have—her mother’s love—and it is further complicated by the pastor’s affair with her mother. Olivia knows what she has done is wrong, but that only enhances the pleasure.

As she ages she begins to yearn to make a cobbler herself, but her mother won’t buy her the peaches. So when she is fourteen, she gets a job. “I would buy my own damned peaches,” she says. The teenage rebellion has begun. On Friday nights, she makes her cobbler, and because she has spent all those years watching her mother, her cobbler is an exact replica: “I didn’t change a single step or ingredient, so my cobbler tasted as good as my mother’s, even better eaten off a plate instead of my fingers.” Her mother is not happy that Olivia is making cobbler because she doesn’t want Olivia to become like her; she says to her, “If you was life smart, you wouldn’t try and be anything like me.” But Olivia can’t understand that because all she wants is for her mother to love her, and from what she has seen, baking a cobbler is the way to express one’s love.

When Olivia is a junior in high school, her mother arranges for her to tutor the pastor’s son, Trevor, who is a senior. For the first time in the story, the peach cobbler disappears from the storyline. Olivia and Trevor become friendly, but even in their first session, Olivia is attracted to him and considers, for the first time, how desire can turn dark: “In that moment, I understood how enough desire could drown you, take you all the way under.” In time, they kiss, make out, and finally have sex.

When Olivia comes to their final tutoring session, she brings a peach cobbler for Trevor’s mother. While standing in the front hall, waiting for Trevor, she sees a new framed photo: Trevor with a beautiful, light-skinned girl in a green prom dress. Olivia learns from Trevor’s mother that this girl is from a nice neighborhood in town and goes to the same private school that Trevor goes to. Olivia thinks, “A Woodbury Academy girl from Hillcrest. Whose mother hadn’t been fucking his father for over a decade.” Of course, Trevor had never mentioned her, and we can feel Olivia’s disappointment in her anger. She is unable to eat the cobbler that she brought: “In the dining room, I could barely swallow a bite, but Miz Marilyn and Trevor dug into the cobbler. They both said it was the best they’d ever had.” Trevor then pushes his plate to the side and eats directly from the pan. The son has become the father, the daughter her mother. Again, Olivia’s anger surfaces: “I wanted to stab him with my fork.”

When Olivia gets home, she and her mother have a fight. Olivia finally understands that her mother has been with the pastor all these years for their own good—to pay the rent, the bills, to keep the lights on. “Why couldn’t you leave me out of this?” Olivia asks her, only now seeing that the tutoring was all orchestrated by the pastor and that she was never seen as an equal to Trevor, that she would never have been the one he would choose. Only then does her mother waver: “You could’ve said no,” her mother whispers. She had been trying to raise a daughter who would stand up for herself, who wouldn’t become the woman she is. Instead, Olivia followed in her footsteps, making a cobbler for a man who would never treat her as an equal. But Olivia stands up for herself in this moment: “I swear,” she says, “my life won’t be anything like yours. Because it will be sweet and it won’t be crumbs.” For years, she has remembered what her mother told the pastor, and she now uses it against her mother in her rage.

Philyaw uses the peach cobbler to underscore the coming-of-age arc, as we watch Olivia grow from a girl into a young woman, as we see her beginning to understand the ways of the world. The peach cobbler stands in for desire, for love, for expectations, and Philyaw so nicely uses it to explore the nuanced relationship between mother and daughter. But a fruit cobbler carries additional meaning as well—it is a uniquely American dessert, thought to have originated in the American south in the nineteenth century, when Black slaves were quite literally cobbling together ingredients to make desserts for their masters. Seen in this light, we can see what a perfect object this was to build a story around—a dessert that consists of layers and centuries of meaning—and how Philyaw’s story is all the richer because of it, a coming-of-age story built on food and desire.