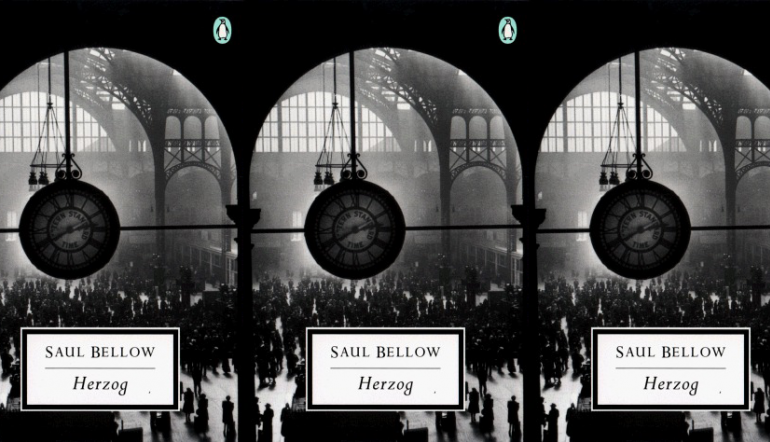

Reading Herzog in 2018

Saul Bellow’s novel is often characterized as a rich portrait of a mind in crisis. It’s also an exploration of the role of history—and memory—in personal life. The novel follows the eponymous character, a middle-aged, twice-divorced, neurotic academic born in Montreal and living in New York. Herzog is sometimes summarized as a chronicle of midlife crisis—Moses Herzog travels impulsively from New York to Martha’s Vineyard, Chicago, and his run-down house in rural Massachusetts, always seeking a grand confrontation or reunion that doesn’t go the way he’s planned. As he travels, he dashes off letters to everyone from Heidegger to his second ex-wife. He writes—and imagines writing—rambling missives addressed to psychiatrists, ex-lovers, lawyers, and long-dead family members. Herzog is a book about a mind that ricochets between self-deprecation and grandiosity, and a character who walks the border between coherence and insanity.

Saul Bellow’s novel is often characterized as a rich portrait of a mind in crisis. It’s also an exploration of the role of history—and memory—in personal life. The novel follows the eponymous character, a middle-aged, twice-divorced, neurotic academic born in Montreal and living in New York. Herzog is sometimes summarized as a chronicle of midlife crisis—Moses Herzog travels impulsively from New York to Martha’s Vineyard, Chicago, and his run-down house in rural Massachusetts, always seeking a grand confrontation or reunion that doesn’t go the way he’s planned. As he travels, he dashes off letters to everyone from Heidegger to his second ex-wife. He writes—and imagines writing—rambling missives addressed to psychiatrists, ex-lovers, lawyers, and long-dead family members. Herzog is a book about a mind that ricochets between self-deprecation and grandiosity, and a character who walks the border between coherence and insanity.

But as I alternated between reading Herzog and the news—of asylum-seekers treated as criminals, of the recent legitimization of the travel ban, of the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court—I especially noticed the novel’s interest in the impact of history on personal life, and in the ways in which personal memory is inseparable from historical narrative. The novel layers the present and the past, the personal and the historical, jumping around in time and place to create a full picture of Herzog’s state of mind. The character is, in some ways, oppressed by memory and history and is self-critical of his impulse to remember: “To haunt the past like this—to love the dead! Moses warned himself not to yield so greatly to this temptation, this peculiar weakness of his character.”

This is one of the novel’s central questions, one of Herzog’s battles with his own mind. What is the use of spending time ruminating about family origins in a country that rewards efficiency, innovation, and (often misplaced) self-confidence? Herzog, who sometimes considers himself a sort of incurable romantic (and whose academic subject is the Romantics), often revisits memories of his childhood as the son of Russian Jewish immigrants in Montreal and Chicago:

Napoleon Street, rotten, toylike, crazy and filthy, riddled, flogged with harsh weather—the bootlegger’s boys reciting ancient prayers. To this Moses’ heart was attached with great power. Here was a wider range of human feelings than he had ever again been able to find. The children of the race, by a never-failing miracle, opened their eyes on one strange world after another, age after age, and uttered the same prayer in each, eagerly loving what they found.

As soon as he gets nostalgic, however, he condemns that nostalgia, that collection of “softening, heart-rotting emotions, black spots, sweet for one moment but leaving a dangerous acid residue.” His reminiscences are characterized by moments of intense presence in which the past takes on a sensory reality that outstrips the literal present.

Of course, nostalgia for Herzog is a double-edged sword—memory gets him into trouble. Furious at his ex-wife Madeleine, who has an affair with a friend of Herzog’s, Herzog impulsively flies to Chicago to “confront” them. He visits his late father’s home in the city, where he picks up “an old pistol” that belonged to his father. He also takes a wad of rubles, which he used to play with as a child. Though he goes to Madeleine’s house with murderous intent, he’s unable to commit the crime. On another day, gun and rubles still in his pocket, Herzog gets into a car accident—it’s the loaded pistol wrapped in old-world money that gets him arrested. Nostalgia—for childhood, for his father, for the old world—is made literal in the pistol and the rubles. Clinging to symbols of the past—and expecting them to solve problems in the present—is foolish, Bellow suggests.

Still, many of the novel’s most vivid and lyrical moments come from Herzog’s compulsive remembering. Retelling stories is a family habit: Herzog’s father tells the story of his life “ten times a year.” The question of memory haunts Herzog: “These personal histories, old tales from old times that may not be worth remembering. I remember. I must. But who else—to whom can this matter? So many millions—multitudes—go down in terrible pain.” In Herzog’s struggle with the past, Bellow dramatizes on a personal level what’s always an issue for nation-states: how to learn from the past without idealizing it or rewriting it to fit national agenda. The novel asks what it means to be American, a question that’s always entwined with the ways in which the country views history and crafts origin narratives. When a lover of Herzog’s claims he’s not a “true, puritanical American,” he’s upset: “That hurt! What else was he? In the Service his mates had also considered him a foreigner.” This exchange sheds light on Herzog’s constant retellings and remembrances—they are a sort of proof of his “American credentials.” Herzog’s personal histories complicate, on a microcosmic level, narratives of what an American is.

Herzog’s final reckoning with the past unfolds at his house in the Berkshires, where he lived during his tumultuous second marriage. He characterizes the house: “Herzog’s folly! Monument to his sincere and loving idiocy, to the unrecognized evils of his character, symbol of his Jewish struggle for a solid footing in White Anglo-Saxon Protestant America…. But enough of that—here I am. Hineni! How marvelously beautiful it is today.” The novel closes with Herzog’s realization that he’s “done with these letters.” The sentences are short, and the present moment takes on the hushed, vivid stillness of the memory sequences. Herzog is, it seems, finally present—but it’s a presence utterly reliant on personal memory and its intersection with history. Presence brings Herzog relative peace, but the amount of time devoted to dwelling in earlier years suggests there’s something necessary about recalling—and retelling—the past with visceral intensity.