Reflecting on Imre Kertész’s Fatelessness

The minute I put my feet on the road, I feel vulnerable. I have been to Krakow three times in my life, but we always avoided visiting Auschwitz. Now, after decades, I am here with my eighty-five-year-old mother. It is only forty-one degrees Fahrenheit and I feel cold already.

My mother was brought up as a Protestant in Hungary. At the age of six, she asked the religion teacher to show her God. She was humiliated for her impudence. How dare she ask such a question? The little girl who later became my mother was inquisitive and wanted to “see” God. Instead, she ended up spending an afternoon kneeling on dried corn in the corner.

This incident might have laid the foundation for her later atheism, which was also fueled by the Communist system. But, despite her departure from religion, Protestant values are still very well planted in her psyche. Just recently, I heard her suggest to my agnostic children not to pray, but to instead spend a few minutes every night in silent reflection, thinking about the good things and the bad things they did that day.

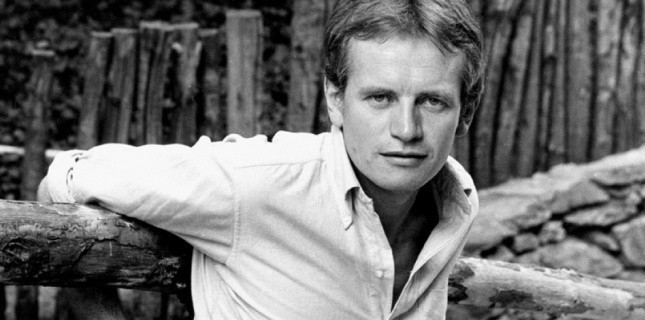

Evaluation is non-existent in Imre Kertész’s auto-biographical novel, Fatelessness, which is about a fourteen-year-old Hungarian boy, Gyuri, who is taken to Auschwitz. I was stunned by the novel’s narrative voice—completely devoid of judgement. The child’s lack of hindsight or foresight eventually helps him survive.

“Fatelessness” is another word for “faithlessness.” Gyuri is not a practicing Jew; a few words in his ID single him out. Ultimately, he is just thrown in with the lot, suffering the “fate of the Jews for abandoning the Lord.”

***

Because my mother was a “war child,”—having lived through WWII and the malnourished 1950s under soviet terror, never leaving her home place—food is very important to her. I remember her stories about having to eat noodles from a mop bucket delivered by the Russian soldiers, or her nightmares from seeing famished people butchering the carcasses of frozen horses in the streets. She is a passionate cook. Every meal is savored and ceremonially taken at nearly the same time every day.

On the evening of our visit to Auschwitz she cannot enjoy her meal at the hotel. She had friends who died in Auschwitz. Her classmates, like her, were thirteen years old when Hungary was occupied by the Germans and the mass deportations took place. She keeps talking about her friend, Klara.

In Auschwitz, every child under the age of fourteen was gassed on arrival. I’m trying to imagine the man at Birkenau registration sitting in front of the ramp at the crossing of the train rails, behind his small desk—at a type of “hockedli,” as my grandmother would have called it, using one of the many Yiddish words that had seeped into our everyday Hungarian. Kertész describes the selection process: “Everything was working well, everything ran smoothly, everyone was in his place and attended to his function, precisely, cheerfully, like a well-oiled machine.” So, how did the administrator feel about the children? Did he care? Did he pray every night asking for the end of the war, avoiding any thought of the good and bad things he had done that day?

***

In Fatelessness, Gyuri was joyous when they finally arrived at Auschwitz and could leave the cattle car. The waiting prisoners who were ordered to take away the new arrivals’ belongings were alarmed seeing him and his teenage friends. “‘Zescajn’ [Sixteen], they whispered from every direction,” and Gyuri laughingly agreed that he would lie about his age.

I look at a photograph of the same railway crossing at the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum. In the foreground a woman in civilian clothing is talking to a man in a striped prisoner uniform. She is affectionate, her head wrapped in a headscarf tilted to the side, and he seems stiff with a large belly—probably a better-fed member of the Sonderkommando, the Jewish men who were forced to work in the crematoriums before being gassed themselves. Is this a hello or a goodbye, or a warning?

***

When my grandfather returned from three years of military imprisonment in Siberia after WWII, he told my mother to stay put and not to rebel against anything that would soon follow. They became members of the Communist Party. It appealed to their sense of social justice, while also proving to be a means of survival. Like Gyuri, they wanted to survive by being “good prisoners.”

Soon enough, the cleansing and years of terror began. Having a working-class background was an advantage, but on top of any skills or knowledge, you had to acquire the doctrines of Marxism-Leninism. You had a good life as long as you agreed with the government. My mother became a leftist for life and now she is still liberally minded, bitterly observing the same pattern in present-day Hungary. She is a pensioner, and an outsider, and allows herself to be as critical as she likes.

Kertész wrote his debut novel, Fatelessness in the years between 1960 and 1973, and it was first published in 1975 in Hungary. This was the peak of the golden age of socialism. Hungary was opening up to the West as the “shop window of the Soviet Bloc.” There was no sign of open resistance against the system. While closely watched, people were happy with the little freedom they had. Censorship silenced the critical voices of the intelligentsia, and many of them emigrated. On its publication, Fatelessness was “received with compact silence in Hungary.”

This silence echoed through my youth, hence this journey with my mother to Auschwitz has a special meaning for me. I was a teenager when I escaped from socialist Hungary through the Iron Curtain, leaving home and family for good. Prior to my defection, I had not talked about my plans to my parents, too worried that they would try to hold me back. It felt as though I had to tear myself away to grow. So every time I see my mother again and every time we say goodbye, for her it might mean that her daughter is disappearing. Every time we reconnect we know that time is running out on us.

***

My mother is dragging her eighty-five-year-old body, which is dangerously overweight for her tired heart, through the bumpy streets of Auschwitz. She keeps telling our fellow-travelers what she remembers, how the people were shot into the Danube in Budapest. When her pregnant aunt asked a soldier “Why are you doing this?” she was threatened with being pushed into the line with the Jews. I have heard this story many times before.

I feel that my mother’s presence on this journey is very important. She is a witness. From her mouth all that we see becomes reality. Otherwise, all that we see is very unreal, a gift for a Holocaust denier. Like a film-set, everything is smaller than expected, all too tight. I cannot imagine the masses having to line up in the foreground every morning and every night. Tourists crowd the yard now, trapped in an absurd silence. Even the guard’s tower seems too small, nothing like in the films, where they are shown from a lower point of view. Yet, my mother seems to be molding into this setting as if she has shrunk.

***

We enter the gas chamber and the crematorium in silence. The walls are blackened by smoke. In his novel, Kertész mentioned the smell, “sweet [and] sticky, mixed in as it was with that already familiar chemical scent.” By now we know that the people in here died in ignorance. So, the black walls are not matted with their fear, but with the horror of the Sonderkommando. I don’t dare to look at anyone. I grab my mother’s hand. Her grip is hot, reassuring.

Many months later my mother tells me what this visit meant to her: she had seen the beginning, all those Jewish people being deported from Hungary. As a child, she did not know where they were taken. It is a full circle for her, for she has seen the end of their journey in Auschwitz, and, nearing the end of her own life, has found closure.

Kertész never found closure. He struggled with depression through his art. “In all respects my existence is horrible, except for writing: so I write and write to endure my existence, to justify it.” Fatelessness ends in a bitter tone. You can taste it in the smoke, the inertia of humanity that allowed all this to happen, culminating in our “darkest hour,” leaving us with the nuclear threat present today. When he received the Nobel Prize in Literature, Kertész finished his acceptance speech by saying, “And if you now ask me what still keeps me here on this earth, what keeps me alive, then, I would answer without any hesitation: love.”

Image: Auschwitz 1 (Henrik Sommerfeld, 2016)