Remembering Henry Bromell

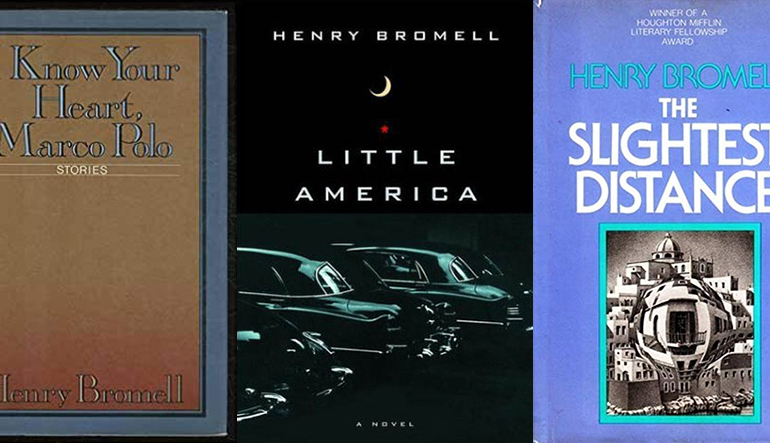

I met the screenwriter and novelist Henry Bromell, born on this date in 1947, through Tillie Olsen in 1973. He was already publishing stories in the New Yorker at the time, and had been her student at Amherst College in 1970 (Tillie was now in residence at MIT). I had written her from Ploughshares, praising her debut collection, Tell Me A Riddle (1961), and asking her for new work. Tillie responded and alerted to me to Bromell, and also to Scott Turow and Fred Pfeil, also from Amherst. Bromell’s stories were soon to be collected in The Slightest Distance (1974); they reminded me of F. Scott Fitzgerald in their wit, nostalgia, and focus on a patrician State Department family, and on Scobie, the family’s writerly son.

That year I was editing a special “realism” issue of Ploughshares, affirming varieties of realism in the face of pronouncements about its obsolescence. Turow wrote a review of Olsen’s first novel, Yonnondio: From the Thirties, for the issue. He had also recommended a story by Pfeil, which I included. Earlier, publisher Seymour Lawrence had put me in touch with Tim O’Brien, who then sent me a chapter of his first novel; that made its way into the issue, too. When Tim moved to Cambridge to become a Neiman fellow, I asked him to co-edit a fiction issue with Bromell and me. Bromell included a story by a friend, Meredith Steinbach, whom he’d met at Iowa, where he had been teaching; he also solicited a story from Mary Lavin, and wrote an admiring profile of her. “Her people feel more than they think,” Bromell wrote. “She builds these characters from gesture, mannerism, speech, dream, work, with a language that is rich, suggestive, and lyrical.”

Bromell remained in Boston until the publication of his second collection of stories, I Know Your Heart, Marco Polo, which appeared in 1979. He once invited me for drinks and dinner to a Boston apartment he shared with a stylish career woman who wasn’t a writer, but who might have been a photographer or graphic designer. They seemed confident, admiring, and happy with each other. I remember stiff martinis, Bromell slouching on a futon as we chatted, and my sense of being presented to the woman as the mendicant amusement. Shortly afterwards, Bromell left for Hollywood. I continued sending him copies of Ploughshares there, and hoped he’d keep in touch as an advisory editor, forward any writers he found to us, and perhaps send us work of his own. He wrote me in 1980:

Here, where the sun shines almost all the time, there seem to be many readers, many more than the Mythology would have us believe. In fact, more people buy more books in LA than in any other place in these united states. Question: what KIND of books? Who knows. I prowl around, and all I can tell is that there are people here who have read MY book, and enjoyed it for what it is, or wants to be, which is more than can be said of, say, New York generally, in my experience.

Years passed. Then I discovered his name among the credits for one of my favorite TV shows, Northern Exposure, which ran from 1990 to 1995. He was listed as story editor, and then as writer for several episodes himself. In the spring of 2001, he sent me a note at Ploughshares to say that he had a new novel coming out from Knopf—Little America. He was having a book party at his parents’ house in Cambridge, and it would be good to see me. If Bromell had “gone Hollywood,” I thought, and had sold out fiction writing for TV, then Little America proved that the writer had not only survived, but grown, and was making a comeback.

By this point, he had married and had a son. Always a slender, handsome guy, he now looked more grizzled. Sitting on the dinner table at his parents’ house, over which there hung a chandelier, there sat a stack of Bromell’s novel, which was for sale. His father, tall and white-haired and wearing a suit, seemed elegantly at one with guests I recognized as retired Harvard faculty, including my first woman teacher, Anne Ferry, and her husband, David Ferry, the poet and Wordsworth scholar. My own first novel, The Marriage of Anna Maye Potts, had just been published as winner of the Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel, and I had brought a copy for Bromell to the party. He congratulated me on it, read the cover blurbs, and showed it around.

I finished reading Little America a few days later. The novel concerned intrigue in the Middle East during the 1950s—topical thanks to the Iranian hostage crisis and sadly prescient of 9/11, which would come that fall and render the novel more quaint than timely. Reviews were respectable. Part CIA conspiracy thriller, it seems curious that it never made its way to film.

There’s always been a violent side to Bromell’s stories, perhaps registering the shock of learning that his diplomat father was a CIA spy, and also demonstrating that despite his urbane surface, he had dealt with intrigue and violence in his career.

When I wrote to Bromell about his 2000 feature film, Panic, and its humor (a psychoanalytic satire, it deserves the status of Fargo as a cult classic), he mentioned his series Brotherhood, which I watched, and which was based on the Bulger brothers—one a gangster, the other a politician. I never saw his series Fly Away, but did later see Homeland, after one of my students mentioned he had written it, as well as his Fitzgerald film, Last Call. After I ran out of Homeland episodes, I watched the earlier Rubicon. I sent him a rave interview with Navid Negahban (the actor playing Homeland’s Abu Nazir), that my student had done. He wrote back: “Navid is a great guy and a great actor. Funny the cyberspace uproar about Nazir getting into the country . . . We talked to national security people who talked off the record, and they made it clear that it would be frighteningly easy for Nazir to get into the country. Both our borders are completely porous.”

I teased him in June, 2011, about Whitey Bulger’s being captured in Santa Monica, where Bromell lived, as if they might have collaborated in writing Brotherhood, or at least Bulger might have stalked him. I was thinking of doing a career interview with Bromell, but before I could even pitch the idea, I heard of his sudden death, at age 65.

As I watched his shows, I couldn’t really detect the Bromell-written episodes from episodes by others writing under Bromell’s direction. The ensemble product—in which the creator sketches out the idea and story, often writing the pilot before others join in—seems to me, even after years of teaching writing workshops, a mystery.

Most people in the Hollywood film and TV industries don’t seem to read books, just as most people in the book industry, especially in New York, don’t live and breathe “story showing” (although they hope to market bestsellers to popular audiences and to score film adaptations). People in film and TV with literary sensibilities are rare—I think of Yale-educated David Milch, whom the New Yorker profiled a few years ago; of Francis Ford Coppola and his founding of All Story magazine; of actor Tony Bill with his reputation for hosting benefits for the Paris Review in his restaurant; of Judith Rascoe, who like Bromell had moved from being a brilliant short story writer to scriptwriter for adaptations of Robert Stone’s novels; and of Ruth Prawer Jabawla, Richard Price, and Chris Offut. Henry Bromell, however, carved out his own remarkable career as a stand out at Showtime. He offered intelligence, complexity of character, and a cultural vision combined with wit and intensity and he wrote and produced with an integrity that joined literature to popular TV and film.