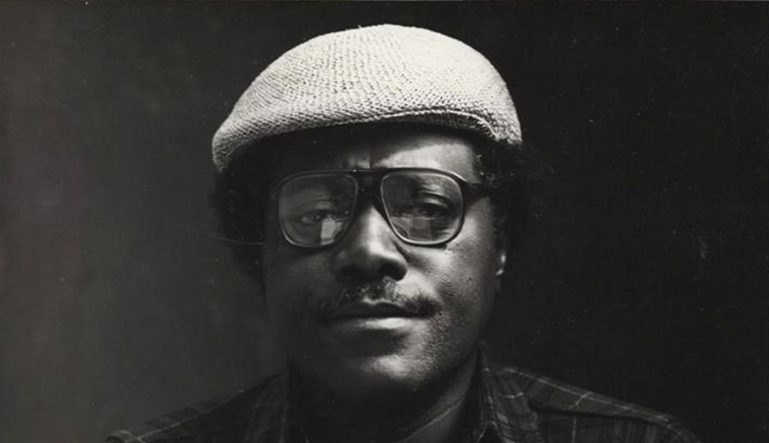

Remembering James Alan McPherson

I first met Jim McPherson when he was twenty-five to my twenty-six and finishing his law degree at Harvard. A mutual friend introduced us because I had just returned to my Harvard PhD program from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Jim was considering taking an MFA there. I’d read none of Jim’s work and had no idea that he’d published in the Atlantic, had studied with Alan Lebowitz, had been mentored by Edward Weeks, and was finishing his first collection, Hue and Cry. I described my Iowa experience to him: that I’d begun a novel, encouraged by Richard Yates, and then when Yates left to write a Hollywood script, had been discouraged enough by Nelson Algren, his replacement, that I suffered writer’s block. Except for Yates, I’d felt marooned. Jim thanked me, but went anyway, and worked briefly with Yates, who, according to Blake Bailey’s Yates biography, told him: “They’re rushing you. Slow down.” and started “to tease through McPherson’s paragraphs, pointing out all the little things that needed to be ‘fixed’ prior to publication.”

I first met Jim McPherson when he was twenty-five to my twenty-six and finishing his law degree at Harvard. A mutual friend introduced us because I had just returned to my Harvard PhD program from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Jim was considering taking an MFA there. I’d read none of Jim’s work and had no idea that he’d published in the Atlantic, had studied with Alan Lebowitz, had been mentored by Edward Weeks, and was finishing his first collection, Hue and Cry. I described my Iowa experience to him: that I’d begun a novel, encouraged by Richard Yates, and then when Yates left to write a Hollywood script, had been discouraged enough by Nelson Algren, his replacement, that I suffered writer’s block. Except for Yates, I’d felt marooned. Jim thanked me, but went anyway, and worked briefly with Yates, who, according to Blake Bailey’s Yates biography, told him: “They’re rushing you. Slow down.” and started “to tease through McPherson’s paragraphs, pointing out all the little things that needed to be ‘fixed’ prior to publication.”

In the next few years, I finished my PhD; couldn’t find work; met my wife, Connie; and began Ploughshares with Peter O’Malley and some local writers (including a few Iowa alums) who frequented the Plough and Stars pub in Cambridge. I kept following Jim’s work, especially his Atlantic cover interview with Ralph Ellison (which inspired my own Ploughshares interview with Yates), his journalism about the Blackstone Rangers, and Hue and Cry. I wrote him a fan letter, c/o the Atlantic, in 1973 and asked him for a story for the special realism issue I was editing. He asked his agent to return unpublished stories to him and promised to send “the better of the two” along. He hand-delivered the hilarious “I Am an American.” He had typed the manuscript on his flight east from San Francisco, and after it appeared in Ploughshares in 1974, he asked for the manuscript back, but it had been thrown out by our typesetter, which annoyed him.

I like to think that he was deliberately turning to our literary magazine as a cause, having been disillusioned, as Allen Gee relates in “Old School,” the longform essay published as a Ploughshares Solo last fall, by the Atlantic’s publishing an article that argued that heredity rather than environment limited black intelligence—an article he had strenuously opposed as a contributing editor.

Our first real collaboration came many years later, when we coedited a fiction-only issue of Ploughshares in 1985. Jim was teaching at Iowa by then, having left the University of Virginia, where he’d felt that he was both window dressing and a target of envy. Elbow Room had been published in 1977 and had been out of print when it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1978. He’d been one of the first MacArthur Genius Grant fellows in 1981. But then he’d undergone a bitter divorce and lost custody of his young daughter, thanks to what he later described as the racist establishment in Virginia, and the invitation to teach at Iowa had been a blessing.

As we approached sorting through submissions, what mattered to us both—in what seemed a confused and hostile literary climate—were the stories themselves. Mostly, our visions overlapped. Jim championed work that questioned cultural clichés and that chafed against closed mindsets, especially those concerning “style.” He sought and favored stories, as he wrote in the Washington Post, that reflected America’s “diversity, touch[ed] a variety of its people, laugh[ed] at its craziness, distill[ed] wisdom from its tragedies, and attempt[ed] to synthesize all this … without going crazy.”

We collaborated, again, on the 1990 double issue of Ploughshares. Following the magazine’s tradition of themed issues, Jim had proposed selecting work related to the notion of “confronting difference,” with models such as Stephen Crane’s “The Monster” or Sherwood Anderson’s “Hands,” but then Don Lee, as managing editor, suggested narrowing the difference to race and joined in the collaboration. In the editing, we rejected submissions where the inclusion of characters of color seemed arbitrary, and where writing perpetuated racial clichés. We were looking for awareness, sensitivity, and responsibility.

The 1998 collection Fathering Daughters: Reflections by Men was our next collaboration, this time with Helene Atwan of Beacon Press, in which we solicited original essays from a range of prominent writer-fathers about their bonds with their daughters. Jim contributed his own essay, “Disneyland,” where he described his efforts to sustain a close relationship with his daughter, Rachel, in her growing up, despite his limited visitation rights. Where the father-daughter bond was culturally under strain at the time, we hoped the essays we gathered filled a certain void and encouraged ongoing conversation and healing.

Jim guest-edited his last fiction issue of Ploughshares for the fall issue of 2008. I had returned as interim editor-in-chief, following Don Lee’s twelve-year tenure as my successor. Jim had published Crabcakes (1998) and A Region Not Home (2000), but at this point, serious health issues had begun to trouble him. Still, he rose to our occasion. In his introduction, he mentioned “neighboring”: “If there is a common thread in the stories here, I think it must be the communal effort to gain perspective on the highly complex areas of our fuzzy and fragmented American reality.” He saw hope in the candidacy of Obama as an omni-American. “One source of his appeal is that he thinks and operates beyond race and class and sexual orientation—beyond all the social categories that function as substitutes for a transcendent American identity.” This, of course, described Jim’s own agenda.