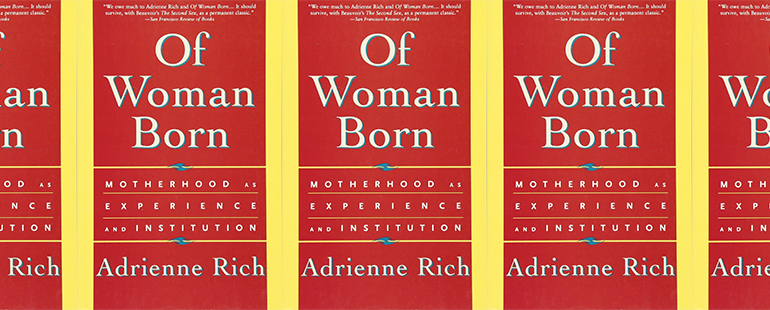

Rereading Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution

Eight months into the pandemic, I reread Adrienne Rich’s 1976 classic Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. I read it sequestered in a suburban house with husband and two children, all of us working, schooling, playing, living within its four walls, hemmed in first by an early Saskatchewan blizzard, then public health regulations limiting in-home gatherings to no more than five. I read the book—or tried to read the book—while Miriam, seven, and Pilgram, four, rolled cars on the floor beside me, ran like airplanes, asked me to slice an apple, asked to go to the snow hill, climbed my body like a snow hill, pushed furniture together to approximate a snow hill, and wailed that they couldn’t find their mittens. I read—or tried to read—while remembering the first time I read Rich’s lucid prose a decade ago, and the way silence stretched, luxurious and free.

It is easy to forget how groundbreaking Rich’s first prose book was, with its blend of research, personal experience, and theory, and its exposé of the patriarchal expectation that mothers be passive, silent, self-sacrificial carers. As she notes in the introduction to the tenth-anniversary edition, in the early 1970s “there was nearly nothing being written on motherhood as an issue.” Rich broke silences by admitting the deep ambivalences at the heart of mothering, the extraordinary love and secret fury. She reported on psychoanalytic theories of gender formation, delved into histories of women’s oppression, called for men to step up to caregiving roles, and criticized obstetrical practices that robbed women of their agency. When Of Woman Born came out, Rich had already been a widely acclaimed poet for a quarter of a century, but this book received more attention than any of her previous publications and polarized reviewers. It’s hard to overstate how influential the book was among readers, activists, and, later, scholars.

I’ve long found personal resonance in Rich’s description of the struggle to be home with young children while also seeking to do intellectual and creative work. She writes of the agony of incessant interruption, and she writes frankly of the rage that can result. When she names the aching impossibility of finding long enough stretches of time to do the work of reading and writing, of thinking and creating, while sharing full days and spaces with children, I feel this tension down to my toes.

What I didn’t expect in the rereading of Of Woman Born, however, was how uncannily similar Rich’s descriptions of the mid-century institution of motherhood would sound to my experience of pandemic. She writes of times, “in bad weather or when someone was ill,” when she and her three small boys “sometimes passed days at a time without seeing another adult except for their father” and how the children’s emotional needs were “vaster than any single human being could satisfy, except by loving continuously, unconditionally, from dawn to dark, and often in the middle of the night.” She writes of later remembering “the apartment in winter where pent-up seven- and eight-year-olds have one adult to look to for their frustration, reassurances, the grounding of their lives.” My pent-up seven-year-old has two adults to look to, and still some days this whole situation seems impossible. My pandemic experience, reduced to an atomized household, exposes the mid-century lie of a self-contained and self-sustaining nuclear family: one woman (or even one set of parents) cannot possibly meet the sum total of a child’s needs, regardless of whether she or they are concurrently working for wages.

The pandemic has also exposed the degree to which feminist gains have still relied on caregiving by women: middle-class mothers may be more likely to go off to work now, but the (generally women, generally underpaid) teachers, daycare workers, healthcare aides, and cleaners continue the work of tending to children, elders, and domestic spaces. When a global crisis rendered many of those caregiving helps inaccessible to middle-class people, it was still women who disproportionately picked up the slack, and it became clear that the powers that be considered the double binds of childcare for working parents a personal challenge rather than a collective one. In other words, the pandemic exposed both the ongoing social expectation that mothers take the lead with domestic labor and child-rearing at home and the economic inequities that still devalue the work of caregiving and domestic labor, whether at home or outside it.

In her 1986 introduction, Rich notes that the changes in the decade since her book’s publication seemed mostly “cosmetic”: the “working mother with a briefcase” hadn’t changed the system but been folded into it and, if anything, economic policy had made life worse for the class of women “without briefcases” who had been working all along, a vastly disproportionate number of them women of color. She writes, “In the ten years since this book was published, little has changed and much has changed. It depends on what you are looking for,” and I am left to wonder if the claim still stands, 45 years later.

This assessment is just one aspect of self-rereading in the 1986 edition, in which Rich confesses that in generalizing her own life she had failed to address the complexities of other classed and raced experiences. By the 1980s she’d learned better from reading and talking with Black women like Audre Lorde and Angela Davis, Chicana women like Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, Asian women like Joy Kogawa and Nellie Wong, Native American women like Paula Gunn Allen, and working-class white women like Tillie Olsen, all of whom she cites as writers who have “challenged and amplified my thinking.” Rich insists in the 1986 introduction that “race and class make a difference of even the most basic shared experiences among women.” Among others, she offers the concrete example of sterilization: as a young “white, middle class, educated woman in the late 1950s,” Rich “had to plead and argue for sterilization after bearing three children”—she even had to provide her husband’s signature—and, at first, she counted this a generalizable feminist concern for reproductive rights. Only later did Rich realize that the same institutions she had to fight for the right to not bear more children “were exerting pressure and coercion to sterilize large numbers of American Indian, Black, Chicana, poor white, and Puerto Rican women.” Notably, racialized sterilization abuse persists to this day. “Little has changed and much has changed.”

Rich is a beacon of self-revision, self-correction: having written the tome on The Institution of motherhood, she ended up fracturing her own totalizing theory with a picture of the many institutions—gender, sex, race, class, education—that in intersecting ways debar women (and men) from a free and creative experience of parenting. In her 1984 essay “Notes toward a Politics of Location,” Rich writes that the problem with many early 1970s white feminists “was that we did not know whom we meant when we said ‘we.’”

Who are “we” pandemic mothers now? Rereading Rich rereading herself disrupts my temptation to generalize from my own cloistered COVID life, the very challenges of which are underwritten by racial, economic, and educational privilege: I am a white tenured professor on sabbatical. Mothers who are single parents, who are under- or unemployed, who must work in-person, who’ve lost their health insurance, who care for not just children but elders, who can’t get good internet access for remote schooling, who are trying to breathe in what Christina Sharpe calls the weather of white supremacy, who—people of color in particular—are experiencing heightened risks of COVID-19—these mothers’ challenges tower over mine, as real as mine may be and as risky as it is to quantify struggle.

A veritable cottage industry has arisen to talk about women’s fate during the pandemic: studies on the disproportionate household and caregiving labor working women engaged in both before and during the crisis; worries about women leaving the workforce and lost feminist gains. But again, who are “we”? Women, myself included, writing op-eds, this piece included, are likely to be privileged professionals, but countless experiences of mothering exist, and they shape mothers’ disparate and even competing needs. For example, advocacy around pandemic schooling has often shown a lack of awareness of other experiences. Parents who could stay home with their children or otherwise arrange care often advocated for school closures without accounting for those who rely on school for childcare, not to mention other crucial supports. Others called for schools to stay open without taking full account of teachers’ concerns for their own safety or family needs. Those who worked for more creative structural revisions often found governments unwilling to value (read: fund) these solutions.

There may be no singular best answer in an impossible situation, but the question remains: how do we find the kernel of shared struggle, the channel of solidarity into which we can direct our energies, not only for our own good but for the other mothers around us? What would it take to stretch out from our atomized lives and ask other mothers, in other social locations, “What are you going through? What do you need to flourish as a human? What do your children need?”

This question of solidarity across difference was increasingly central to Rich’s project from the 1980s until her death in 2012. Her writing insistently called for accountability and nuance, for strategic coalitions, even given the risks. As she put it in the poem “Sunset, December, 1993,”

Rich calls for a similar intersectional effort in the 1986 introduction to Of Woman Born, one that recognizes the impossibility of “protected” “individual life” or “innocent” literary production. She asserts, “I would not end this book today, as I did in 1976, with the statement ‘The repossession by women of our bodies will bring far more essential change to human society than the seizing of the means of production by workers.’” Instead, she writes that while she’s still committed to “sexual and procreative choice,” she sees these autonomies as inextricably bound with racialized, decolonial, and economic struggles for recognition of full personhood, a strong voice in democracy, and robust justice for all members of society.

Surveying the headlines today, I imagine Rich shaking her head and reminding us that feminism hasn’t failed women. There are many feminisms. White liberal feminism has failed us, as it was sure to do all along, because it didn’t seek a genuine revolution, and it didn’t seek to serve all women.

I imagine Rich questioning participation in “the workforce” as the measure of women’s liberation. Is it really the feminist dream to work 50 or 60 hours a week for stagnating wages while relying for childcare on other underpaid women? Is the solution to this problem really primarily for men to take on more domestic labor? Could we imagine other structures, an institutionalized valuation of the inevitable and important work of caregiving? Could we see those at the frontlines of caring—teachers, nurses, healthcare aides, cleaners, cooks, childcare providers—paid in accordance with their vital importance? Could we in North America dream of and work for paid caregiver leave, a living minimum wage, a 30-hour full-time workweek, a universal basic income?

Asking such questions of the systems and of each other, imagining otherwise, could initiate the ever-expanding network of solidarities and visions Rich sought to create. Such efforts may ask some of us to reread our very selves, to revise the very terms of the investigation. And so in the moments between zipping coats, wiping faces, and trying to piece together coherent sentences, I look up from my little life. I practice the reframing Rich suggests so piercingly in the poem “Draft #2006”: “They asked me, is this time worse than another. // I said, for whom?”

This piece was originally published on January 12, 2021.