Research Unleashed! And Leashed.

I knew I had a problem when I started envying my dog’s cone collar.

Now, my dog’s problem was a hot spot. Allergic, itchy, hot, and double-coated, my German Shepherd had chewed her hind leg raw over the course of a single evening.

My problem was research. Engrossing, surprising, discomfiting and endless, my novel-in-progress was generating fact after fact, but very little story.

Neither of us could resist the itch of our obsessions, which were self-ruinous and spreading. For my dog, the vet imposed a “cone of shame”—a demoralizing, and mostly effective, plastic barrier denying

her access. This is what sparked my envy, for what kind of restraint could I impose on myself, a writer whose project requires research—research that also derails the project at every turn?

Latest Findings: Novel Research Leads to Pornography

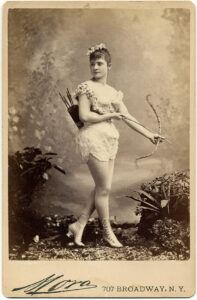

How does research become a problem? Well, for one, it’s larky. You wonder if your character’s pants would have buttoned or zipped, which means you need to know about the invention of zippers, and then, hours later, you’re pouring over sketches of Victorian pornography.

A surprising number of research inquiries lead to vintage porn.

It’s justifiable porn, too—this porn is laced with noble purpose! Because whatever you find in the research process could lead your story to its True Destiny. You start off writing about one character or a particular setting, but research curls its finger and beckons you to follow. For instance, a museum photograph of courtesans led Amy Tan to scrap her 200-page work-in-progress, reconsider her grandmother’s history, and write The Valley of Amazement. When Sue Monk Kidd was researching the life of abolitionist Sarah Grimké, the “tantalizing detail” of a birthday present—a 10 year-old slave named Hetty—led to the rich, dual-voiced narrative of The Invention of Wings.

Research rewards us with information, serendipity, storylines, validation. Do census records confirm a theory about a character’s origins? Well done, Sherlock! In a single day of research, we can veer from outrage at the confines of a prison cell to laughter at an insult in a letter. Research lets us plunge into engrossing depths and flit superficially from topic to topic. Plus, we rationalize: it’s good for us. Right?

Not always. Not when we lose sight of the objective—a finished project—and find ourselves standing in the kitchen pantry of our imagination, addled, wondering, “What did I come in here for again? What was my goal?”

Cones and Collars For the Research-Obsessed

So, maybe your research has become a hot-spot: you can’t leave it alone, it dominates your life. How can you rein it in? Here are some tips for leashing your obsession, and making it serve you:

Say Yes, Then Say No. Many writers wholly indulge the research impulse in the beginning stages of a project, then stop in order to write. As Amy Tan puts it, “You get to do your anarchy, try this and try that, try everything, and then apply craft. Trade in the longhand pages for the computer screen. That’s the taskmaster, the person wielding the whip…[Y]ou sit in this room, and clean up this mess.”

The anarchy phase of discovery might last months, even years. Elizabeth Gilbert labels these phases “seasons”—in one season of research, Gilbert produced five shoeboxes of note cards and a 70 page synopsis of The Signature of All Things. When she moved on to a season of writing, Gilbert’s novel became almost “a paint-by-numbers operation.”

Pause, Scratch, Move On. I can’t wait to try this idea from my friend Anne Panning: find a nice pad of paper and a lovely box. Whenever you’re writing and have the urge to look something up—and potentially lose your way— simply write your inquiry on a piece of paper, fold it up, and put it in the box. That’s it. Document the question and move on.

This ritual is both fussy and momentary—it allows you to pause, express your curiosity, and keep on writing the story. Other writers like Toni Morrison use the placeholder “DK” for “Don’t Know”—and Roy Kesey’s list of research inquiries, from Necessary Fiction’s “Research Notes,” is hilarious.

Express A Little Research. Enconed, my dog enacts the gestures of scratching but can’t create new damage. If you, likewise, must enact the gesture of writing your research, take a cue from Cathy Day, who documents her discoveries on blogs, Pinterest boards, and a Tumblr. These posts are not essays, Day clarifies, nor are they excerpts from her WIP—and she doesn’t allow this research to overtake the actual writing: “Instead, I play with my bulletin board/scrapbooks as a way into the writing or when it’s time to take a break from writing—instead of smoking.”

What Research? Of course, there are writers who disregard—or say they disregard—research entirely. According to Edward P. Jones, “probably 98 percent” of The Known World is entirely fictional, including the novel’s census documents. Faced with strict limits on his time, Jones prioritized writing over research, relying on his general sense of history: “You accumulate facts about the world and about history as you go through your life. And I figured I knew enough about 1855 Virginia to write the novel. … If I say it’s 1855 Virginia, then you’ll believe me until I say something to contradict that.”

Jones’s first piece of advice for emerging writers: “Don’t worry about research.”

Relieve the Pressure. If your research is motivated by anxiety—if you’re worried about getting something “wrong”—remember your focus: are you preparing a lecture series, or writing a novel? Are you striving for intellectual authority or compelling storytelling?

Yes, for you fact-obsessed writers, here’s another fact: writers do make research mistakes, and these make it into print. Websites list Shakespeare’s historical inaccuracies. (According to Cracked, many stories are saved historical inaccuracies.) Even Ian McEwan —who followed a neurosurgeon for years in the course of researching a novel—gets it wrong sometimes. Even Divergent series author Veronica Roth apologized to fans for her “mistakes.” These writers continue to draw in readers. A gap in credibility did not ruin them forever.

My favorite response to a factual error comes from E.L. Doctorow, whose first novel, Welcome To Hard Times, features a scene in which his starving characters feast upon the leg of a prairie dog. A reader confronted him in a letter:

“Young man, when you said that Jenks enjoyed for his dinner the roasted haunch of a prairie dog, I knew you’d never been west of the Hudson. Because the haunch of a prairie dog wouldn’t fill a teaspoon.”

Doctorow says, “She had me. I’d never seen a prairie dog. So I did the only thing I could do. I wrote back and I said, ‘That’s true of prairie dogs today, Madam, but in the 1870’s…’”

So if nothing else, keep this fact in mind: a writer can do anything she pleases with the story of a dog’s leg.