Rethinking the Strong Female Character

The “strong female character” often falls into two categories: the masculinized tough-girl type, or the woman who quietly bears heavy burdens. Gender identity interacts with other identities in infinite ways, and the latter of those two tropes tends to disproportionately fall upon black women in fiction. Recent innovations that undercut this trend are both necessary and exciting; Randa Jarrar’s Him, Me, Muhammad Ali and Brit Bennett’s The Mothers both come to mind. What makes a strong female character? The horizon of answers to this question broadens more every year.

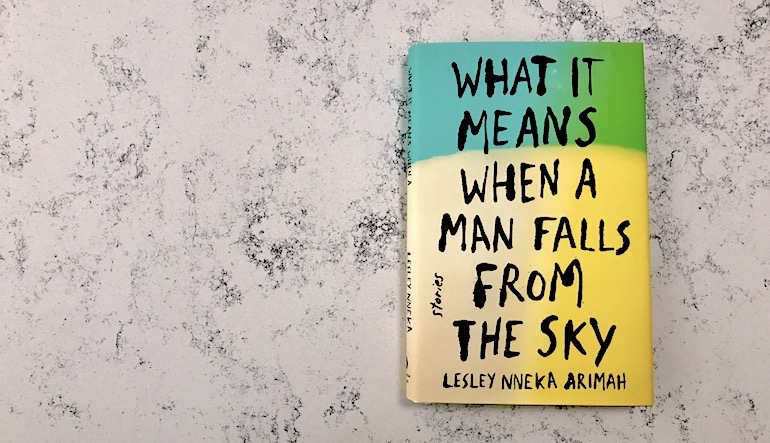

In Lesley Nneka Arimah’s new short story collection What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky, masculinity acts neither as a foil for comparison nor as a standard for female characters’ strength. Instead, Arimah explores new ways to think about the intersections of femininity, strength, and vulnerability.

One particular story, “Who Will Greet You At Home,” resonates with these themes even more directly than the others. It takes place in an all-female world where mothers craft their children out of raw materials ranging from mud to human hair, and then the mothers of the new mothers can “bless life into” the creations.

It’s rare that we see a portrayal of an all-female society that isn’t a variation on the Amazon warriors (the Wonder Woman film recently reminded us of this tendency). Arimah instead introduces a culture of domesticity that centers rituals of child-creation and motherhood. The narrative itself, like its arc of reproduction, takes place without any male influence.

As the story unfolds, we learn that Ogechi has fought with her mother over the impracticality of her past attempts at making children because she used “soft” materials like cotton and wrapping paper (her mother admonishes, “Bring me a child with edges . . . ”). Ogechi must pay another woman to bless her creations, and since she has no money, she pays in “joy” and “empathy”:

The woman had already taken most of her empathy, so that she found herself spitting in the palms of beggars. She’d started on joy the last time, agreeing to bless the yarn baby only if Ogechi siphoned a bit, just a dab, to her [ . . . ] Ogechi tried to think of it as an even trade, a little bit of her life for her child’s life.

Here, a character’s emotional strength has literal value, and it can be exchanged for goods and services—in the case of the blessing, even life itself. What does this currency of selfhood mean for how feminine identities take shape? When the story appeared independently in the New Yorker, Arimah spoke to Deborah Treisman about how this inclination toward the supernatural colors her approach to characterization:

I can take a very human desire, insert it into a supernatural world, and watch humanity become grotesque. An element of surrealism in a story can put pressure on a character in ways that would be impossible in our natural world, and when you make the world surreal but keep the characters human, the juxtaposition creates interesting textures in the narrative.

This approach to “narrative texture” allows Arimah to craft characters who possess types of strength that we’re not used to seeing in fiction. In Ogechi’s world, reproduction becomes a craft of creative energy; in the world of the titular story “What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky,” the main character works as a mathematician who can use an infinite “formula” to calculate and consume the grief of others. Arimah artfully presses her characters into these situations, and then seems to step back and allow them to take shape on their own.

The clichéd categories of the “strong female character” discussed earlier, while incomplete, demonstrate how a woman’s strength is all too often defined either by how she emulates men or by how she puts up with them. Of course, this issue of relationality is nothing new, and is not confined to fiction. Simone de Beauvoir outlines it in one of the opening paragraphs of The Second Sex (1949):

Thus humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him; she is not regarded as an autonomous being. Michelet writes: “Woman, the relative being . . . ” And Benda is most positive in his Rapport d’Uriel: “The body of man makes sense in itself quite apart from that of woman, whereas the latter seems wanting in significance by itself . . . Man can think of himself without woman. She cannot think of herself without man. [ . . . ] He is the Subject, he is the Absolute—she is the Other.”

When writers sit down to characterize a strong female character, they must confront this societal roadblock—the notion that the female is, by definition, not “the Subject” at all. Through her experimental narratives, Lesley Nneka Arimah finds new ways to navigate this roadblock; sometimes by working around it, and sometimes by imagining new worlds where it simply does not exist.

Amy Jo Burns reviewed What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky in the post “This Spring’s Best Books” earlier this year.