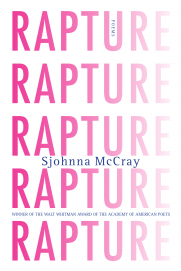

Review: RAPTURE by Sjohnna McCray

Rapture

Rapture

Sjohnna McCray

Graywolf Press; April 2016

72 pp; $16

“Father and Son by Window,” the opening poem in Sjohnna McCray’s debut poetry collection Rapture, has an ephemeral feel; the poem rises like a plume of smoke. “You sing, soft winds and blue seat,” it begins, a line more about sound and mood than action, with such rich consonance that it practically begs to be read aloud.

This nicely sets up the book as a whole, hinting at McCray’s talent for sound, while gently nudging readers in the direction the poems will take. Many of Rapture’s main subjects are introduced here on page one: the relationship between a father and a son, the pleasures and irritations of the domestic sphere, and—of course—love, in all its forms.

The love between father and son is present in the second poem, too, but in “How to Move,” love is manifested as attention to the physical body. The line breaks in “How to Move” flawlessly measure the information in beats:

I cannot look at anything

so black as my father’s leg

or used-to-be-leg below the knee[.]

If the poems begin with the speaker as son and caretaker to his father, they proceed from here to observe and imagine the speaker’s parents’ romantic relationship. McCray summarizes his parents’ relationship at times—his father and his mother he calls “the unassuming black and the Korean whore / in the middle of the Vietnam war” in one poem—but over the course of the book, he also dignifies them with a nuanced romantic life as lovers beyond their roles as parents.

The many lyrical moments offer a way of entering into the parents’ relationship and acknowledging their attraction to each other, while also preserving the mysterious sense a child feels that it is impossible to fully explain or even understand one’s parents’ relationship as romantic. Is anyone ever truly capable of understanding his parents as a couple, as an individual unit within the larger framework of the family? McCray at least comes closer than most of us.

Finally, the parents’ story gives way to the speaker as an adult, entering into his own romantic relationships, first as flirtations and finally realized in sexual as well as domestic terms. The book’s exploration of love between men—and, to a lesser extent, of love between a man and a woman as it is viewed by an external observer—places great emphasis on care-taking. But the caregiver’s role is rescued from sentimentality by McCray’s frank observations of the imperfections of the human body, and by how delicate the relationship between care giver and receiver is. Marriage in “Something Wicked” is described thusly—

There is no finer stitch than this:

marriage: always counting the details left,

always waiting on the marbled foot.

One of the most interesting features of McCray’s work is the way it bluntly presents the human body—even in the throes of erotic longing, the speaker notes the deformities, warts, scars, sweat and stray hairs that make even the most perfect lover human. Young, old, fit, disabled—bodies in any condition are objects of imperfection and close scrutiny to McCray, as when in “Comfort Woman,” a poem ostensibly about prostitution as a form of care-giving, the speaker observes

the prickly hairs, the moles and bumps,

the scarred trenches along the shoulders

of her clients. In poems that otherwise emphasize sound and mood and images of beauty, these visceral descriptions stand out sharply, providing refreshing contrast.

This is a highly controlled, musical book that privileges flawlessly smooth sound and evocative moodiness, but there is no lack of story here, either. Rapture delves deep into visceral material, mapping family and the human body and the relationships that concern both.

It’s also worth mentioning that the book moves extraordinarily well from poem to poem; the arrangement builds momentum and the poems seem very much in dialogue with each other. Read in order, the poems tell a chronological story that opens with a son taking care of his father, shows readers the development of that relationship, and then extends it outward into the son’s own romantic life.

Rapture was selected by Tracy K. Smith as the 2015 winner of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets.

Elizabeth O’Brien lives in Minneapolis, MN, where she earned an MFA in Poetry at the University of Minnesota. Her work—poetry and prose—has appeared in many literary journals, including New England Review, Diagram, Sixth Finch, Whiskey Island, decomP, PANK, CutBank, Ampersand Review, Revolver, Swink, and Versal. Find her on Twitter: @elzb_obri.