Round-Down: Reading As Luxury, or Necessity?

Garbage collector Jose Gutierrez gives new meaning to the phrase “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” The 53-year-old Colombian man has been collecting children’s books out of dumps for the past twenty years in order to provide a makeshift library to the city of Bogota. He now houses over twenty-thousand titles rescued from the dump.

Gutierrez’s efforts are not in isolation. Plenty of creative minds the world over have been finding innovative ways to bring books to the world’s poorest kids. Book vending machines have popped up in Washington D.C., books are available on bikes in Seattle and San Francisco, and there are book buses in South America and Asia. Little free libraries remain popular, and a string of vandalism has outraged their community members. Recently, the media was captivated by a Utah boy’s plea to the mailman for junk mail to read. The mailman, touched that a young child was asking for reading material rather than electronics, put out a call for people to donate used books to the young boy.

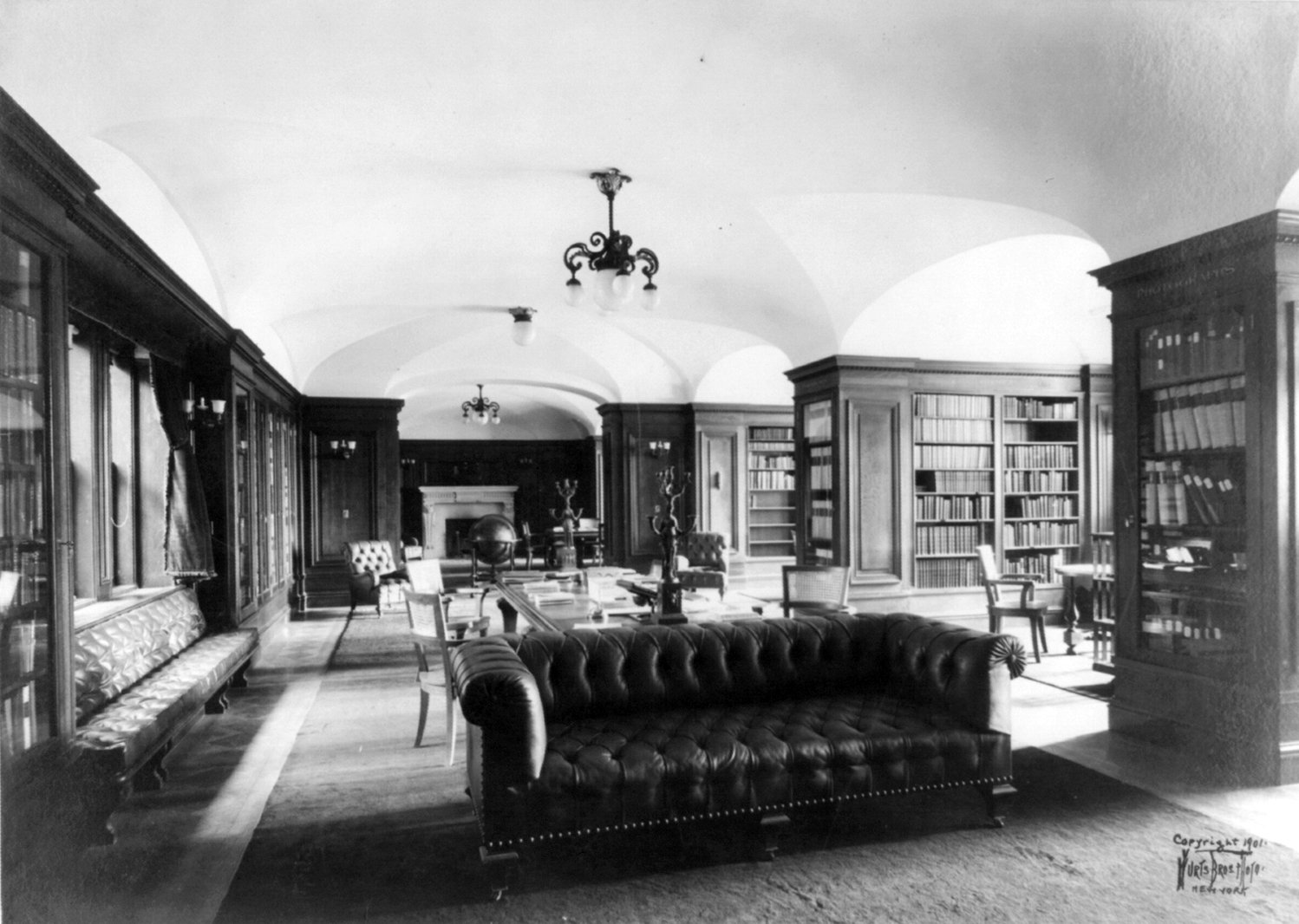

While libraries are a great model for delivering literature to communities, many reports point out that branches are often located far from poor neighborhoods, a phenomenon not unlike that of the food desert, where many grocery store chains opt not to build stores in low-income areas. It’s easy to take for granted our access to books. It’s easy to forget that reading is luxury.

And yet, as Audre Lorde writes, poetry is not a luxury, especially not for women or minorities (those most often likely to be poor, even by today’s standards). She considers “poetry as the revelation or distillation of experience, not the sterile word play that, too often, the white fathers distorted the word poetry to mean—in order to cover their desperate wish for imagination without insight.” In shifting the definition of poetry—which I take here to be reading at its most compressed and pure form—she ultimately reverses a capitalist notion of reading as a luxury, an activity meant for those with disposable income. She writes, “For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.”

The actions of those seeking to provide books to all communities are akin to creating, as Andrew Carnegie said, a “never failing spring in a desert.” For Carnegie, the herald of the steel expansion in America who gave ninety percent of his fortune to charities, “a library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people.”