Sacredness in the In-Between

I grew up in Laredo, Texas, a small city on the U.S.-Mexico border. Laredo is not a well-known place. It’s far away from Texas’s bigger, more popular cities, and it gets scant attention from national media outside of occasional mentions about cartel violence, the immigration crisis, or the time Donald Trump arrived there in 2015 and claimed that his life was in grave danger.

Living in Laredo in the 1980s and early ’90s, before NAFTA and before the turf wars between rival cartels decimated the tourism industry, I understood the border between the two countries to be little more than a legal distinction. When I was in private school for kindergarten, many of my classmates lived in Mexico and commuted across every morning. My father’s dentist was in Mexico. We frequently visited my cousins on the other side, stopping for Cokes at the Cadillac Bar and buying duty-free Crown Royal and Kools before heading back to our house. This was life in South Texas: no one actually lived on one side of the border or the other. Reality was far more fluid, and far blurrier.

The Nahua had a fantastic word for this blurriness: nepantla, a state of in-betweenness, of being in the middle of something. Use of the term nepantla was popularized by poet, writer, feminist scholar, and fellow South Texan Gloria E. Anzaldúa in her 1986 work of Chicana scholarship, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. “Living between cultures results in ‘seeing’ double,” she wrote. “Seeing from two or more perspectives simultaneously renders those cultures transparent. Removed from that culture’s center you glimpse the sea in which you’ve been immersed but to which you were oblivious, no longer seeing the world the way you were enculturated to see it. From the in-between place of nepantla, you see through the fiction of the monoculture.”

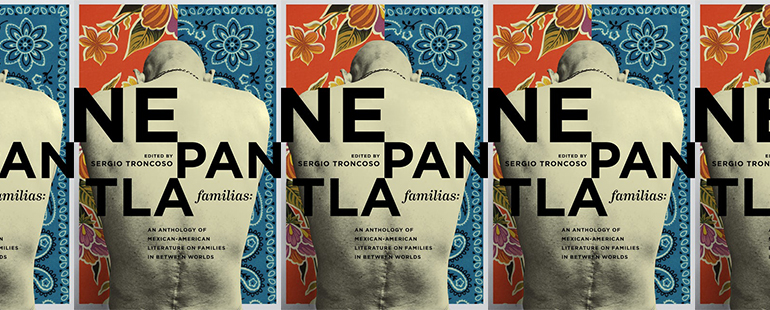

It is in this in-between place that Sergio Troncoso has chosen to situate his latest anthology, Nepantla Familias, out this spring from Texas A&M University Press. Through fiction, poetry, and nonfiction by Mexican American authors, Nepantla Familias explores families living along the border and how being in the middle of worlds impacts their lives. In a place where cultures, languages, cuisines, religions, and customs intersect and blend together, and where Mexicans are made to feel like trespassers in a land that was once their own, how does this experience echo through the generations, and what can we learn from it?

In the opening essay of the collection, “Here, There,” David Dorado Romo describes how he was eager to leave his hometown of El Paso, Texas, and go on a quest to learn Hebrew in order to better understand the Bible. On a trip to Israel, however, he found himself on a different border, this one dividing Jews and Arabs. The trauma of forced separation was palpable to Romo, having seen it his entire life. In the essay, he speaks of liminal spaces—from the Latin word limen, meaning threshold—which he says anthropologists classify as inherently unstable and dangerous. But though the border may be unstable, he ultimately returned to El Paso after traveling through the Middle East, preferring to see the creative potential in a place of so much flux. “In Nahuatl, to inquire about someone’s name you ask, ‘Quen timoteca?’ meaning, ‘How were you planted?’” Nepantla, Romo says, is where his roots are.

For others, however, roots are more elusive. Francisco Cantú, Ploughshares contributor and author of the acclaimed memoir The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border (2018), brought his mother to Monterrey, Mexico hoping to find out more about his grandfather, a search he discusses in his essay “Calle Martín De Zavala.” Cantú’s mother did not have a relationship with her father for most of her life, and this trip was intended to be a reclamation and a commune with her own history. Armed with a single grainy photograph taken in 1912, they walked up and down a single street, hoping that something would spark recognition, a memory, a whisper from the past. But if the street held any secrets, it kept them silent, and mother and son were eventually beckoned inside a woman’s home to have some lunch. While the woman cooked, she told the pair all about her life in the snowy sierra highlands before she came to the city, and Cantú had the realization that he knew far more about this stranger’s life than about his own grandfather’s. As they traveled through the state of Nuevo Leon to visit ancestral villages, Cantú felt “a growing awareness of how little we actually had to situate or guide us.” He describes his mother looking for her ancestors through a haze, a familiar feeling for anyone whose family was separated from the place of their birth and relocated elsewhere. This, too, I believe is part of the nepantla—knowing that one can never return to the place that came before.

The notion of nepantla was, and continues to be, life-changing to me on a personal level. Not only did I grow up in between countries, where enchiladas were as American as a hot dog, but I am also bi-ethnic, half-Mexican American and half white. Nepantla is as much within me as without, and acknowledging that there is an interstitial state, that the idea of a monoculture is, in fact, fiction, was enormously healing and allowed me the freedom to occupy a middle space without feeling always that I am lying about who I am.

In the essay “Día de Muertos,” Stephanie Elizondo Griest speaks of what she calls the “schizophrenia of being biracial, of straddling two worlds but belonging to neither” and how this “might be the most Mexican thing about [her].” Remember that Mexico was founded by a forced mixing of two cultures, Spanish and indigenous—the entire country functionally in a permanent Nepantla state. “The single most uniting fact of our Mexicanidad is that it is a negotiation for us all,” Griest writes. “Some aspects of our identity, we inherit; others, we must pursue.” These are powerful words considering that the term pocho is still used by Mexicans to mock those who have lost their culture and become too Americanized. This frustration was immortalized by Edward James Olmos in the 1997 film Selena, when he says it is exhausting being Mexican American. “We gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans, and more American than the Americans, both at the same time.” When asked, How do you identify? which answer is correct? Mexican? American? Both? Neither? Depends on the context?

In “Elote Man,” David Dominguez writes about feeling pride as he’s able to repair the irrigation system on his lawn, only to repeatedly have to tell his neighbors that he is not a laborer available for hire, that he owns the house and the lawn. He goes to Home Depot for supplies and hears the cashier speaking Spanish to all the men in front of him in line. He says he gathered together all of his Spanish words, “gathered them together as if they were family members I saw once every ten years, great uncles and aunts I longed to hold as if holding them might link me to my ancestors now that my grandparents had passed.” But when he gets to the front of the line the cashier switches to English, and the author then questions his own Mexican-ness, wondering if she would have addressed him in Spanish if he’d gotten the Funions instead of the spicy Cheetos with lime.

At some point, what can you do but laugh? In “Family Unit,” a short story from Rubén Degollado, the narrator has traveled from South Texas to the central Oregon coast for a vacation with his wife, and finds himself arguing with the English proprietor of seaside cottages over which unit the couple will rent. “This wasn’t just your average gringo entitlement,” Degollado deadpans, “this was your from-overseas gringo entitlement, the old kind where gringos not only expected the best for themselves, but also told you what was good for you.” The story takes a far more serious turn later on, but the author’s clever employ of humor in his interior monologue speaks directly to the uncomfortable spaces in which many Mexican Americans find themselves. The narrator is a teacher in a border town and, though he is on vacation, he has repeatedly been asked to discourse on the wall, on the kids in cages. “Out here in Oregon . . . I found myself leaning toward being Chucky Chicano, Mr. Activist, Mr. Wave My Flag, Mr. Speak Spanish to the Workers Whenever He’s Got the Chance.” I will reiterate: living in the nepantla can be exhausting.

It can also turn you upside down, as Sandra Cisneros learns after moving to Mexico, an experience she writes about in her poem, “Jarcería Shop.” “And here I am at fifty-eight / Migrating in the other direction / With a truck hauling my library. I live al reves, upside down. Always have. Who called me here? The spirits maybe. A century later. To die at home for them / Since they couldn’t.” It is a beautiful sentiment, dying at home because our ancestors couldn’t, and yet I can’t help feel that Cisneros knows life can’t be lived backwards like that. Cantú’s mother learned in Monterrey that the border, fluid and porous though it is, is somehow also frustratingly solid, as stark and impenetrable as the bold black line dividing the two countries on a map.

I first read Gloria Anzaldúa’s work years ago when researching my second novel, but I didn’t really internalize the concept of nepantla until I attended a conference last year and sat in on a panel featuring writers who all identified as biracial and/or bi-ethnic. There, I heard Los Angeles Poet Laureate Luis J. Rodriguez, who is Mexican American and a member of the Rarámuri indigenous people of Chihuahua, speak of nepantla as a sacred distinction. Some indigenous peoples, he said, believed that those who lived in in-between states were blessed, that they had access to states of being unavailable to everyone else. I cannot tell you how powerful this was for me to hear, a person who’d always walked around feeling like two disconnected halves of a whole, that I was not fully a person, that I was doomed always to have only one foot in anywhere. For those of us who are biracial or bi-ethnic, or for those people who feel that neither gender expresses their true identity, a feeling of sacredness in the in-between is beautiful indeed.

In his introduction to the anthology, Sergio Troncoso says he believes the feeling of nepantla is a universal one. “Anyone who has left their home and tried to find a new one in a strange place—at times welcoming and at times hostile—they should find themselves in these pages . . . And anyone who has crossed any border to create who they are . . . and suffered the consequences for it—they will find their fellow travelers, their kindred spirits, in these pages.” I think he is absolutely correct. Monoculture is a myth, and one of many fictions I hope to see dismantled in my lifetime. And I believe embracing nepantla, the in-between, as well as the people who exist in in-between worlds, who will live and die in that liminal space, is the key toward healing lifetimes of division. If we see the world for the hazy, blurry, funny, upside-down place it is, and choose to believe it is sacred to be two things at once, just imagine what could come next.

This piece was originally published June 15, 2021.