Sadness, Metaphor, and Pedagogy in The Sword in the Stone

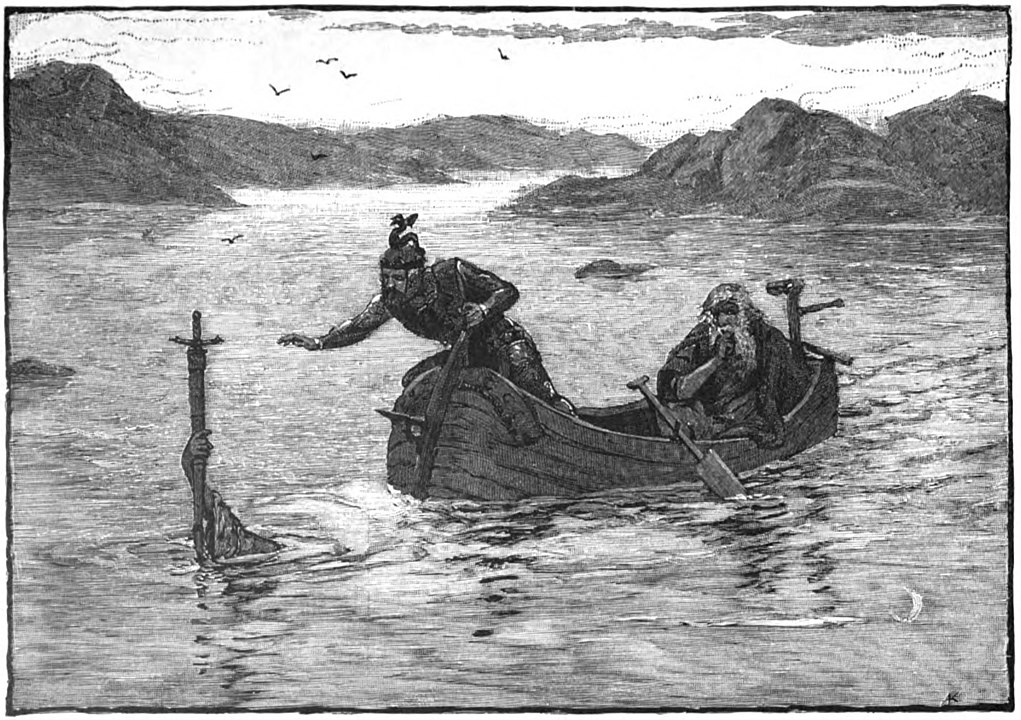

In The Sword in the Stone—the first book of T. H. White’s Arthurian saga The Once and Future King, published in 1938—a young Arthur is feeling restless and sulky. His brother Kay isn’t interested in horsing around and hawking with him anymore. Times are changing. Armor is donned, adult responsibilities are assumed, and Arthur is left behind. After all, he’s a foster boy, a child of little importance—or so he thinks—and the world will surely pass him by. But his teacher Merlyn believes differently; he knows Arthur is so very much more than he appears. Sick of looking at his long face, Arthur’s stepfather shoos him away to Merlyn’s study for advice and a little cheering up, and Merlyn tells his pupil, “The best thing for being sad … is to learn something.”

Merlyn privileges a particular kind of learning—ruled, on one hand, by inquiry, and informed, on the other, by leaps of imagination. One can’t scientifically study birds—the mechanics of flight, the social life of the flock, etc.—without first imagining what it’s actually like to be a bird. But what Arthur finds in his imagination is human life recast—specifically, its relationship to power and violence. Like all anthropomorphic fables, the moral of Arthur’s story has to do with people, not animals. In fact, morals and fables themselves are human constructions; no hawk reflects on the morality of its kill. What’s important for White and Merlyn, then, is that Arthur learns about his own kind, but with metaphorical flourish; Arthur is tenor and animal is vehicle.

In other words, Merlyn’s pedagogy is rooted in metaphor—that age-old method by which we might transform the world around us. It’s not so much that Arthur becomes a fish, a merlin, an ant, a goose, a badger, but rather that he is compared to them as a means of understanding his own character in relation to theirs. What kind of leader will Arthur be? To Merlyn’s mind, a good leader must understand what it is to be both predator and prey, fish and bird. A good leader must be able to see the world from a range of perspectives, from the “chartless nothing” of the sky to the “strange under-water world” of a castle moat.

Merlyn’s magic relies on narrative, too—or, rather, the artist’s ability to scramble its traditionally linear trajectory for aesthetic and emotional effect. To put it more succinctly, Merlyn is a poet of transformation who lives backwards. “I unfortunately was born at the wrong end of time,” he tells Arthur, “and I have to live backwards from in front, while surrounded by a lot of people forwards from behind. Some people call it having second sight.” He knows what’s in store for Arthur, and for us. He knows World War II is on the horizon and fascism will make its way across Europe, that norms will be upended and misinformation spread. How, then, does Merlyn keep hope? By learning something. Because, as he says, it’s “the only thing that never fails.”

What we get, then, is a novel full of political satire, fantasy, and anthropomorphic, anachronistic gags. But I believe its central interest is sadness. If sadness can’t be overcome, if it’s truly inevitable, then what is left to do but examine it from different angles, turn it over in our hands? There’s the sadness autocrats feel, alone in their power and fear, like the old kingly pike Arthur as perch meets in his castle’s moat, described as a “vast ironic mouth … his lean clean-shaven chops giving him an American expression…. remorseless, disillusioned, logical, predatory, fierce, pitiless—but his great jewel of an eye was that of a stricken deer, large, fearful, sensitive and full of griefs.” There’s the sadness of mindless work, mindless consumption, and mindless conformity Arthur finds in an ant hill where there are “repeating voices in his head, which he could not shut off—the lack of privacy … the dreary blank which replaced feeling—the dearth of all but two values—the total monotony more than the wickedness: these had begun to kill the joy of life which belonged to his boyhood.” And there’s the sadness of a life given over to constant killing. As a merlin, Arthur roosts among his castle’s hunting raptors, and where he expects to find the freedom of flight, he finds an insular, militaristic world in which a goshawk—perhaps as a nod to wartime trauma—finds himself unable to curb his tendency toward violence. The hawk’s “poor, mad, brooding eyes glared in the moonlight, shone against the persecuted darkness of his scowling brow. There was nothing cruel about him, no ignoble passion. He was terrified of [Arthur], not triumphing, and must slay.”

In every instance, Arthur is made to confront the complexities inherent in power structures, the loss of humanity that results in the single-minded pursuit of power, and the underlying sadness that motivates it. What matters is the learning. Merlyn warns Arthur:

“You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then—to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the only thing for you. Look at what a lot of things there are to learn.”

Merlyn’s teaching is an act of hope, predicated on his belief in Arthur, his faith in the future (in his case, the past), and in Arthur’s destiny. In the context of 1930s England, White’s writerly intention has more to do with encouraging compassion in the midst of unimaginable cruelty than with giving his readers just another take on the old Arthurian legend. Merlyn—as proxy for White himself—conjures up an ideal education, one that privileges critical thinking, the natural world, emotional intelligence, and creativity; there’s something to be said for his method, something to be learned from it, despite history’s (or, I should say, the future’s) overwhelming, inescapable sadness.

And at the ends of his lessons, Merlyn refuses to summarize, to lecture, to give away the meaning—a decidedly twentieth-century literary tactic—but the morals are there, waiting under the surface, and he leaves it up to Arthur to find them. For some teachers, this tactic is scary: What if students fail to find meaning in one class, in a month of classes, in a semester’s worth of classes? What if students take years to come to the “right” conclusion, or what if they never come to it at all? Merlyn chooses the arguably more difficult path, but for him patience comes more easily; after all, he sees Arthur’s coming successes as well as his failures, and what choice does he have but to try, over and over again, to show him that “education is experience, and the essence of experience is self-reliance.”