Sweet and Sour Paris

Recently, travel magazine Afar sent writer Taffy Brodesser-Akner to Iceland. She responded with an interesting essay about looking for and not finding any puffins, an adorable bird native to the island. “Everyone comes to Iceland with a version of Iceland they’ve made up for themselves—a place of infinite happiness or infinite pools or infinite fermented shark or infinite Björk—and a visit to Iceland is very much about that particular Iceland, the one that really exists only in your mind.”

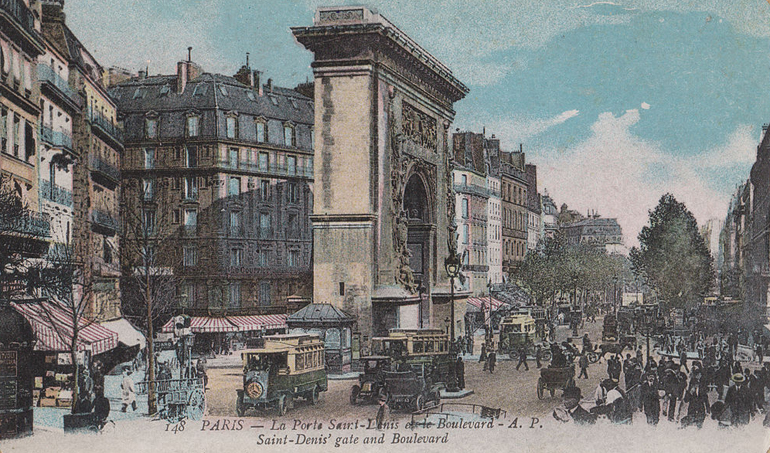

Nowhere is this idea of a place that really exists only in your mind more true than it is in Paris, although many writers seem to want to overlook this. The world’s bookshelves are overstuffed with earnest first novels by fresh-faced expats, backpackers, and dreamers who have journeyed to Paris for one reason or another and were swept up by the beauty, the culture, the food, the wine, the fashion, the scarves, and the Vespas. For a while there was even a Facebook group of expat women who were all writing first novels about Paris. I’m 98 percent sure they all featured sidewalk cafes, croissants, and cute boys named Jean-Claude who will, in the end, or maybe even from the get-go, fall madly in love with them.

Please don’t misunderstand. I love Paris. And I have been known to read a few of those “new in town” Paris memoirs, more than a few, actually. But the more I read about Paris, and whenever I am lucky enough to travel there, I want to know what Paris is really like, not just what I want it to be like. You don’t have to sugar coat it for me. I can take it.

“Whenever somebody asks me about Paris, I feel like I have to lie,” says Eleanor Brown in her short story “Failing at Paris.” “No one says ‘How did you like Paris’ with the same sort of disinterest they might as ‘How was Akron?’ or ‘What did you think of Poughkeepsie?’”

Brown’s story of romantic and pragmatic Paris colliding as she tries to recreate her grandmother’s Jazz Age adventures in the City of Light is just one of a new collection of very relatable and very real essays about contemporary France. Titled A Paris All Your Own, it includes stories by women writing about their unique Parisian experiences without the whole adventure devolving into cloying travelogue. What I learned from these essays is that the Paris of my dreams (and yours, too) probably does exist. But the real Paris is right around the corner ready to make you rue the day you ever heard of the Eiffel Tower.

For example, in France, people speak French. This is often overlooked when expats write about France. Author Maggie Shipstead writes about living in a student dormitory of sorts while visiting Paris on a writing fellowship. In “Paris Alone,” she is not out drinking with her new expat friends or dancing in clubs with boys until all hours. She is studiously avoiding all contact due in part to embarrassment about her schoolgirl French and a garden variety introverted personality—not that there is anything wrong with that. Anyone who has ventured to a country where the language most commonly spoken isn’t their own can understand the terror that can arise when a perfectly pleasant-looking stranger wants to make small talk in an elevator and they lack the language skills to make a benign comment about the weather. Shipstead has been avoiding her neighbor, an affable Swiss composer with a mop of dark curls, for this very reason.

“In France, my aloneness was intensified by my incompetence at the language,” she writes. “The city babbled around me, stray words catching my comprehension, but none of it solidifying into any sense of what was being said. We kept private from each other, Paris and I. It was perhaps like listening to an underwater opera.”

Shipstead isn’t the first to have romantic Paris brush up against workaday Paris and French-speaking Paris. Rosecrans Baldwin and his wife Rachel moved from Brooklyn to Paris for a year to work at an ad agency. His memoir of that time Paris I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down has one of my favorite titles of all time. The book itself takes readers into a world of French dinner parties and provides classic slices of street life as we’ve come to expect from contemporary American-in-Paris novels, but the one thing that separates this book from most others is that Baldwin has a job. His descriptions are of trying to understand and be understood by his co-workers and navigate his way through Parisian office culture. True, it doesn’t rise to Breathless levels of intrigue, but finding out that he’s not quite as witty in intermediate French as he is in his native English comes as a sad realization, but he also wonders if his colleagues’ clunky English is equally misleading.

A Paris All Your Own expands upon Baldwin’s thesis that what the Paris travelers carry around in their heads is in for a hard landing when confronted with the reality of Paris. In “Thirty Four Things You Should Know about Paris,” Meg White Clayton checks off all the tiny details that can derail an idyllic Parisian interlude. Her first visit was with a soon-to-be ex-lover. She advises against this. “I recommend avoiding trips to Paris with lovers who are soon to be ex-lovers,” she says. “Even Paris can only take so much.”

Clayton’s essay is filled with similar roadblocks to the Parisian fantasy. I especially enjoyed her description of the byzantine process for getting tickets to visit the Eiffel Tower, a perennial hot topic of conversation in TripAdvisor’s Paris travel forum. During the visit in the book, she and her husband arrive just as the Tour de France bicycle race is heading for the Champs Elysees.

“It seems random and improbable that every time I find myself in Paris, something remarkable is going on, but the thing is, it’s Paris,” she says. “You really should know that you’ll see some gorgeous thing at every turn.” The rest of her advice is stellar and goes against all the French girl tropes clogging up women’s magazines and style blogs. “Paris does umbrellas better than any place. Bright orange is best. . . . A champagne house name at the edge is optional but the Veuve Clicquot orange is tres chic.” She encourages doing away with table manners when finishing a cup of French hot chocolate. “Oh go ahead. When the only one looking is that adorable dog the woman at the table next to you brought, lick the bottom of the cup.”

Meanwhile, Julie Powell (yes, that Julie Powell of Julie and Julia infamy) tries hard to fall in love with Paris, but keeps falling short. “Even in the handful of hours I did get to myself,” she says, “taking in Notre Dame, walking the Seine, visiting the Tuileries or the Eiffel Tower, it was no good. I wasn’t falling in love with Paris. I could see why I should . . . but I didn’t.” She eventually does find love and romance in Paris—but it’s with a baguette from the corner bakery.

The moral of these stories, if there is one, is that no two travelers have the same experience—of Paris or anywhere else. You are not Julia Child, Zelda Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Serge Gainsbourg, or even Gene Kelly. Vacations are like fingerprints, no two are ever the same.