The Arc of Joan Didion and Annie Dillard

In my mind, Joan Didion and Annie Dillard are linked, two sides to the same coin, one the yin to the other’s yang. This is unfair to both women.

In the late 1990s, I was taking advantage of the office hours of Carolyn Segal—my creative writing professor at Cedar Crest College who I asked a lot of, and who indulged me far more than she needed to—and asked, “Who should I be reading?”

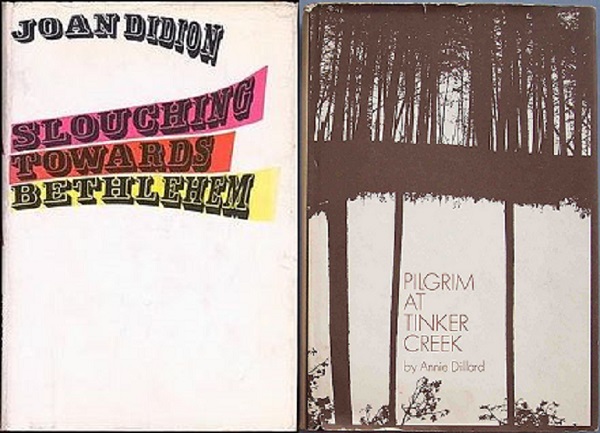

She started rattling off names and titles, so I scribbled down Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem and Dillard’s Pilgrim At Tinker Creek. As much as I’d like to invent another reason, they stood out in my mind because they were women.

A literary troglodyte at the time, I presumed women only wrote poems (based on my experience with Dickinson), romance novels (as I knew of Steel and Collins), or letters for their boss or husband (according to every TV show and movie that premiered in the ‘80s). And there’s always been an association between women writers and the memoir.

In short order, however, they stood out because they were writers whose books I read in one sitting—books that continue to affect my (and many others’) writing. At that point in my reading life, this was no small feat.

I let Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and An American Childhood wash over me, but I studied Didion’s The White Album and Slouching Towards Bethlehem. As a journalist and someone who is fascinated by the ‘60s and ‘70s, I understood that to read Didion is to have the epochal changes of those two decades broken up into component parts, a kind of scrutiny that ought to have diminished the insanity of the age, but instead exacerbated it. The ’60s and ’70s became more inexplicable through the lens of Didion’s essays, not less. You wonder, like she did, how in the hell we’ll get out of this mess.

Didion was praised for being cool (and criticized for being aloof), which was a critique of her persona rather than of her writing. It’s also a criticism of the “just the facts, please” journalism of days gone by, a style Didion did not ascribe to.

It’s true that, with her late husband John Gregory Dunne, she formed a sort of screenwriting power couple (though male writers are not often judged based on their relationships with their wives). And it’s fair to say that she did seem to cultivate a cosmopolitan public image. But is there a male writer whose public image is linked to his work to the degree of Didion?

Didion’s heartbreaking The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights ought to have put to rest (likely gendered) critiques that she’s clinical in personality and craft. But had these deeply personal works about family, love, and loss debuted earlier in her career, she might have been dismissed as fulfilling the stereotype of a “woman writer.” This is a problem faced strictly by femme writers. One strains to imagine Stephen King or Elmore Leonard worrying about how the plot of their next book would have helped or harmed their reputation in this way. Putting Didion (or any writer) in a silo based on superficial traits discredits their talent. For her part, Didion has always blended passion with professionalism. The tell is in the first sentence of The White Album: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

These stories—what follows on these pages—are not a trifle. They are our oxygen. These are not the words of someone above the fray. Didion’s anxieties have always been spelled out on the page.

The critic Caitlin Flanagan insisted in 2012 that women (more than men) understand Didion instinctively, a notion I initially bristled at. But then I reconsidered. Perhaps Didion’s ability to put all of herself—mother, wife, writer, voter—on the page is relatable to women, who intuit what it means to be different things to different people?

No one would say Annie Dillard is aloof. Her life, as described by Pico Iyer last year, bursts at the seams with generosity and collegiality. She’s aware of her amicable reputation—on her website she pleads for people not to send her manuscripts (which calls to mind Emily Gould’s recent article on women writers’ obligation to “be nice” in the publishing industry). Didion would never do this. Didion does not have a website.

While her output may have slowed in recent years, Dillard is an established trafficker of ideas, an academic, willing to be wrong. You won’t find her on cable TV shoutfests or TED talks, but she’s a public intellectual in the classic sense. It’s hard to imagine Didion standing up in front of a class. Where Didion made you wonder about how the world would affect you, Dillard made you wonder how you could affect the world. From Pilgrim at Tinker Creek:

Something broke and something opened. I filled up like a new wineskin. I breathed an air like light; I saw a light like water. I was the lip of a fountain the creek filled forever; I was ether, the leaf in the zephyr; I was flesh-flake, feather, bone.

Here again, I find myself guilty of the very thing I criticize. I apply attributes to Dillard based as much on what I know of her personality as what I know of her writing. But it would be near impossible to do otherwise, since the first person is so much a part of Dillard’s (and Didion’s) writing.

In this context, Elena Ferrante’s decision to remain anonymous, whatever its true intent, is an act of boldness. She’s saying to us, “I’m not letting you get to know me, because if I do, you’ll conflate me with what and who I write about. And I want you to know my stories, not me.”

While I originally linked Didion and Dillard in my own mind because of their gender identities, examining their work shows how limiting that was. Their work could not be more different, but their contributions to our culture (like that of many other women writers, and non-binary writers, and writers of color) are so profound, I’m sure we will be reading them a hundred years from now.