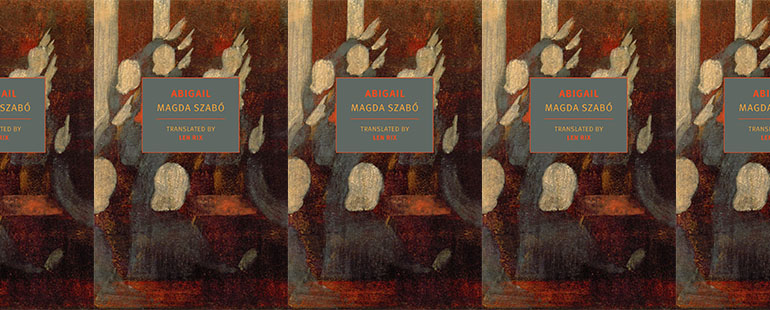

The Art of Dissent in Abigail

The Hungarian writer Magda Szabó is best known in the United States for her 1987 novel The Door, a new translation of which appeared from New York Review in January 2015; in her New York Times review of this translation, by Len Rix, novelist Claire Messud famously wrote that it “altered the way I understand my own life.” In Hungary, however, Szabó’s most popular work is Abigail, now available in English for the first time in a translation also by Rix. The novel, originally published in 1970, tells the story of fourteen-year-old Gina Vitay, who is sent to the Bishop Matula Academy, a Protestant boarding school for girls far from Gina’s home in Budapest. (So far from Budapest, in fact, that the town in which it is located, Árkod, is now part of Serbia.) From the very beginning of the novel, it’s easy to see why Gina’s story has been so popular in the half-century since it was first published. The story is like a fairy tale, in which a wealthy young woman is separated from her beloved father and seemingly enchanted family life, and in which she must then live among people whose indifference to her desires is, if not deliberately cruel, certainly tyrannical. It is also an unusual coming-of-age story—the willful heroine finds her place in society not by learning to comply with its demands, but by learning the art of dissent.

Given that Abigail is set during World War II, dissent was a moral stance, and necessary for the survival of thousands of Hungarians. Hungary was a reluctant ally of Germany during the war and in November 1940 signed the Tripartite Pact uniting the Axis Powers. By 1942, Hungarian forces were fighting the Soviet Union; meanwhile, Prime Minister Miklós Kállay was clandestinely reaching out to the Western Allies with the promise to surrender, should their forces ever reach Hungary. This impossible balancing act came to an end on March 19, 1944, when Germany began its occupation of Hungary. More than a half-million Jewish Hungarians died; another quarter-million survived, many with the help of their fellow Hungarians.

These events form the backdrop of the novel, which begins in September 1943 and concludes in March 1944, a time of great danger for Gina and several of her classmates. At first, though, it seems that the war raging throughout Europe has little effect on the events in the girls’ cloistered world at “the Matula.” Certainly Gina’s attention is initially given entirely to adjusting to the totalitarian environment of the school, where the girls are required to wear not just uniforms but identical hairstyles, are permitted to have no personal possessions, and are forbidden to make any complaints whatsoever in letters home. “They have swallowed me whole. I am no longer myself,” she thinks when her hair is cut and plaited in the standard style. Accustomed to her bourgeois life in Budapest, which included the care of a French governess, afternoon teas and dances at her Auntie Mimó’s, and regular attendance at the theater and opera, Gina is unprepared for the rigors of her new school and is, at first, incapable of coping.

The girls who have boarded at the Matula for years, on the other hand, have developed ways to deal with their thoroughly regulated daily lives. These include two covert traditions that originate with the legendary alumna Mitsi Horn, who arrived for her last year at the school in 1914 wearing a forbidden engagement ring. Mitsi Horn’s classmates, so enchanted with the idea of having a fiancé, but lacking contact with any actual young men, came up with a game in which each girl at the school would be secretly engaged to an item listed in the class inventory; over the following decades, the game became a tradition. Another tradition concerns a stone statue in the school garden. The statue is of a young woman the girls call Abigail. After Mitsi Horn’s engagement ring was taken away, she went to Abigail, “weeping and complaining how wretched she was,” and a few days later she discovered a letter from her fiancé in the pitcher that Abigail holds. Mitsi Horn continued to exchange letters with her fiancé through Abigail, and since then the girls have turned to Abigail for help with their serious problems, on the condition that they never talk about her with strangers.

Gina rejects these traditions as “childish nonsense.” “What an imagination these people have!” she exclaims to herself. “This Abigail, who always comes to your aid! And all this inside the fortress, where we live like soldiers in a barracks and with nothing but biblical quotations on the walls. They are so superstitious they might just as well worship idols!” Nevertheless, just before the first lesson of the term, Gina finds herself “betrothed” to an empty aquarium, loses her temper in a blind rage, and betrays the secret of the girls’ pretend engagements to the school’s director. For weeks afterward, Gina must reckon with “the terrifying self-discipline of the Matula” as her classmates ostracize her completely in a manner that is undetectable to their teachers or prefect. Her classmates are, at least in their temperaments, not so childish as she had thought.

After a thwarted attempt to run away to Budapest, Gina comes to understand that it is time for her to learn the self-discipline that her classmates have mastered. On a visit, her father, alarmed to learn about her attempted escape, decides to entrust her with a secret, the cost of knowing which, he tells her, will put an end to her childhood. “Gina, we have lost the war. In truth it was lost from the start,” he says. “Those of us who know this also know what must be done. We are trying to put an end to the war. If we succeed, countless people will live. Budapest and the other cities, and what is left of the army will be spared. If we don’t succeed, then the loss of human life and the general destruction will continue, and I will be caught up in it, and so will my colleagues.” His fear that she could be kidnapped in order to blackmail him into betraying the resistance is the reason why he had sent her away so abruptly to the Matula, a place “as impenetrable as a prison.” Before he leaves, he asks her, “At all events, stay calm. Will you promise?” Gina vows to fulfill this promise. She later reflects: “All my life I have been a wild thing. . .I am impatient and impulsive, and I have never learned to love people who annoy me or try to hurt me. Now I shall try to learn these virtues, and I shall do so for the sake of my father: for him I shall seek to be gentle and patient.” The purpose of this restraint, of course, is not really to submit, but to maintain the outward appearance of compliance that, in Gina’s circumstances, is necessary for dissent.

As evidenced by its students’ secret traditions, hidden dissent is as integral to the nature of the Matula as its strictures. After a tearful reconciliation with her classmates (during a terrifying nighttime air-raid drill), Gina discovers the exhilaration of living in what she calls a “forbidden forest”: “Like hungry little foxes, they were always on the qui vive, looking to squeeze out every bit of fun they could in the thicket of rules and regulations and constant supervision.” And Abigail, Gina realizes, is the most secretive dissenter of all. When Gina receives a note signed by Abigail (“IF YOU ARE IN DIFFICULTIES, WHY NOT TURN TO ME? YOUR SECRET IS NOT THE ONLY ONE I KEEP”), she glimpses Abigail’s true nature, as “not a mere stone statue but a real person hiding behind it, ready to help anyone with a genuine need.” At once she begins to wonder:

Who are you, Abigail? You live with us here in the Matula, you move among us, shout or smile at us, are so familiar to us that you can walk in and out of the dormitories without attracting attention, or rummage in our pockets and leaf through our exercise books. You always know what we are whispering about, you see everything, and yet no one ever even notices you.

As the war progresses, hiding one’s activities or identity becomes far more than just a way to squeeze out a bit of fun. Just before Christmas, for example, Gina gives falsified documents (smuggled to her by Abigail) to four of the girls at the school, to replace stolen documents that would have shown that some of their parents or grandparents were Jewish. Under these circumstances, Gina must learn not only the self-discipline necessary to keep secrets, but the discernment to see beyond subterfuge to the underlying character of the people, particularly the adults, with whom she lives. This skill, it turns out, is difficult to acquire, and Gina gets just about everybody wrong: the class tutor, whom she thinks of as “a particularly handsome St. George”; the Latin teacher, whom she especially loathes as clownish; the whimsical and charismatic Mitsi Horn; the humorless school director; and even her own boyfriend, Lieutenant Feri Kuncz.

Only with experience can Gina overcome this naïveté. Ironically, she does so with the help of Abigail, whom she once rejected as a childish fantasy. When her father assures Gina that “the dissenter of Árkod,” who posts anti-war and anti-Nazi messages around town, is looking after her, he tells her, “You have known him for some time without realizing who he is. When you discover who it is you will be very surprised.” Though the reader is unlikely to be surprised, Gina certainly is when she figures it out only after the moment of greatest danger has passed for her. In the end, though, and just as the German occupation is beginning, Gina has learned the restraint and discernment she needs to resist authoritarianism.