The Artist’s Journey in What’s Left of the Night

“Weak expression Poor artistry” reads the fictional note in red pencil on Constantine Cavafy’s sheaf of poems sent to the poet Jean Moréas in the novel, What’s Left of the Night by Ersi Sotiropoulos and translated by Karen Emmerich. The line haunts Cavafy in the last three days of a stop in Paris with his brother John in 1897 at the end of what seems to be a European tour. Cavafy would go on to be one of the most celebrated poets in contemporary Greek poetry, but in this moment that Sotiropoulos captures, the thirty-one-year-old is riddled by doubt.

“For years he believed his family could be an advantage for his writing, just as important as his talent or the things he read. A cosmopolitan family was a trump card for a poet,” Sotiropoulos writes. But despite the promise of having all the right schooling – Cavafy spoke English, French, and a little Italian, in addition to Greek – and despite the advantages that come with being born into a good family (despite its decline following his father’s untimely death), Cavafy in his early 30s was not the writer who wrote poems like “Ithaka,” well-known to even those who are unfamiliar with Modern Greek poetry, or “The God Abandons Anthony,” which we see him tinkering with in What’s Left of the Night.

“Leaving Therapeia,” one of his earliest surviving poems, is written in English, and we can see from its cloying dandyisms—like, “Good dinners that make you exultingly swell”—and attempts at effective end rhymes—such as “heart” and “art” and the even more painful closing lines, “So at humble Catikioy let us not rail/ But bid it All Hail!”—that the despairing fictional Cavafy is perhaps right to despair that he will never be the poet he wants to be.

The Cavafy of What’s Left of the Night constructs what essentially amounts to a list of how he could produce better work (a list that will seem familiar to any artist):

‘…art and life were interconnected,’ he thinks, and asks himself how ‘someone with a small, miserable life, hemmed in by prohibitions and fears, unable to let his senses run free, ever hope to fill his writing with such great emotions?’ He’s a clerk at the Ministry of Irrigation, a job that the real Cavafy would hold for 30 years. He worries that his life is ‘squeezed from an eyedropper’ in Alexandria and thinks that if only he lived in Paris, life would be different.

Or perhaps, he thinks in the same breath, what he needs is to set a schedule, that that would do it. Or that he just needs to devote himself entirely to writing ‘without calculating the losses and gains,’ the approach of loving the process of writing without a thought to the immortality he assumed he was entitled to from his family. Or perhaps the problem is with him, something that laid deep within as a flaw, all along, one that would keep him at the level of painful mediocrity.

It’s fitting that Sotiropoulos’s Cavafy finds his way not in a sweeping moment, but in smaller gains. He eventually rejects the idea that his quiet life is a deterrent to creating great art—believable after reading Sotiropoulos’ renditions of his fantasies throughout the three days. His thoughts take him out of his own surroundings and place him into another life that is so vivid it is often difficult to understand at first that the action described has not, in reality, taken place. He realizes that his “passion was internal, subdued, [and] no less tyrannical” than poets like Verlaine and Rimbaud, poets who burned brilliantly but quickly.

The quintessential late bloomer, Cavafy gives hope to all of us who will never be on a 30 under 30 list. His way of writing, too, of adding a few lines to a paper then concealing that paper in an envelope that he would revisit, writing more lines when he felt he had something to add, is an inspiration when the pressure to produce content quickly is, for many, the fact of a writer’s life. We witness this process in What’s Left of the Night when Cavafy is haunted by lines from what becomes “The City”:

As he walked, the lines of a poem he was writing came to mind. Every so often he would pick it up, poke and prod, then let it be. He had looked back at it recently and had been satisfied. Very satisfied. The musicality was flawless, the rhyme effective.

The city will follow you. The roads you wander will be

The same. And in the same quarters you’ll grow old, and see

Such luminous, flowing lines. He repeated them to himself several times, and then the entire poem, savoring each word, each turn from line to line. Yet something wasn’t right. …The city will follow you, he said to himself. Then he picked up the thread at the start of the second stanza, You won’t find other places, you won’t find other seas… But on the corner of Rue de la Paix he was again ringed by doubts. Something felt off toward the end of the first stanza, something bothered him.

Cavafy continues to tinker with the poem throughout the novel, letting us see how such a poet might have lived between doubt and faith in both his own abilities and in allowing words to shape his life. His triumph, in the end, comes when he recognizes the need to set aside the doubt and insecurities sparked by his imperfect poems, allowing him to create not despite his flaws, but because of them.

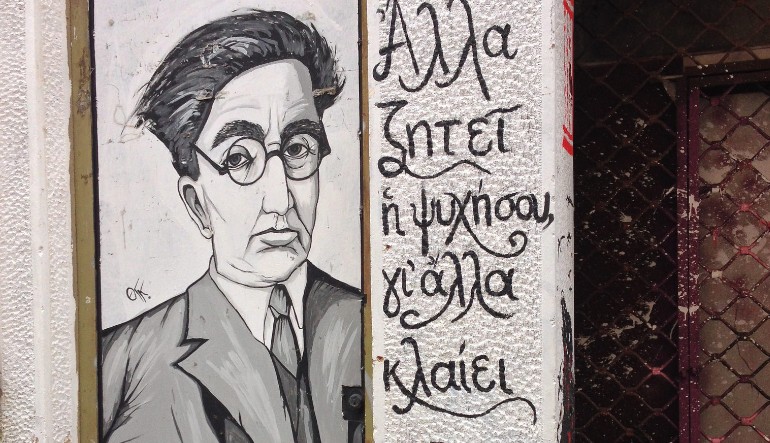

“C.P. Cavafy, Agias Eirinis st.” by Dimitris Kamaras