The Best Writing Advice I Never Gave

A while back a friend of mine contacted me with a good idea: he wanted to collect one piece of advice from a number of writers he knew and pass all of them on to his advanced undergraduate workshop students.

If you’re anything like me, this is the kind of assignment/favor you’ve thought a lot about. It seems that for years, somewhere in my mind I’ve been thinking, “One of these days I’m going to get to a point where people are going to be asking me for advice to young writers.” And now that day had come!

In my (admittedly fairly lame) Walter Mitty dreams about being in this position of wisdom and authority, I’d come up with a slew of concise little gems that the recipients, these bright, burgeoning writers would carry with them for years to come. Invariably, these were—at least in my mind—strikingly astute bits of erudition glazed in a thin candy coating of clever irony; disarmingly simple bon mots infused with self-deprecation; savvy nuggets of insight that in a matter of a few words would knock the recipient’s understanding of the craft of writing right on its ass. Boom!

The only problem was that now that somebody had asked, I couldn’t think of a single decent thing to say. Or, rather, I could think of too many things, none of them quite right.

What was the advice that I had gotten that proved to be essential? I remember the first time a professor discussed the relationship between a writer and her reader as a partnership where each participant did part of the work to create the universe of the story in the mind of that reading. This blew me away, made me rethink my whole conception of audience.

So I could pass that one on, but this felt like someone else’s advice, not anything I’d earned. And this was the problem with most of the bits of wisdom that came to mind: they didn’t feel like mine, either because I hadn’t thought of them, or—more importantly—I didn’t really follow them.

But I knew a couple things, right? I could focus on craft—keep it relevant, easily applicable. Everyone needs a little craft advice. I’ve worked through that stuff. I know craft. Right, then. Here goes…

Point-of-view is everything. It affects each and every aspect of your story, all the way down to the basic facts of the universe!

True. Certainly true. Just take a look at something like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to see just how vital a keen understanding of point-of-view is to a writer’s work. But it’s not really advice, per se, is it?

Let’s try something a little more bold…

Don’t worry about making your characters likable, but work like hell to make them understandable.

Who’s going to argue with that truth bomb? Everyone knows that the less likeable a character, the more fun they are to read about. Plus that little “like hell” bit gives it just the right amount of old-schooly Hemingway-ness. Not bad, Stansel.

Yet it doesn’t quite fit the occasion. This is THE advice I have to give. Am I really going to waste it on a pat little epigram?

What about that question that people ask: where do your ideas come from? (I’ve never actually been asked this, but it seems like something people ask, or say they’ve been asked.) Perhaps I jumped too quickly to craft and needed to take a step back to idea generating…

Read the New York Times so that you can construct a full global world for your characters to inhabit. Read your local papers to give your characters something to do in their own space. I don’t care if you live in Paris or Sioux City—someone close by is getting down to some weird business that you can then use in your work.

Pretty good, but hardly the thing that is going to blow minds. Maybe what I needed was something more basic, but—you know—profoundly basic. Something like…

Read more!!!

Hmm. Maybe not. I didn’t want to come off like a complete asshole.

So I went through a series of possibilities, none of which felt quite right. I wondered, after a while, what parts of my writing process felt essential not only to the quality of my work, but to my happiness as a writer and as a person. And then I thought about this:

A few years ago I got a phone call from my brother. “Would you want to go to a Zen Center in California this summer?” he asked.

I’d been living in Houston for just under a year—transplanted from various cities and towns through the Midwest—and was still not used to the heat and traffic and cockroaches of usual size. I thought about my brother’s proposition for only a second before saying yes. Prior to that summer, I knew the word “zen” mostly as a synonym for “chill.” Need to finish a twenty-page paper tonight? Don’t freak out; just get zen about it. Dealing with too much family at the holidays? Close your eyes, pour another glass of wine, and get zen.

That is to say, I knew almost exactly nothing. But the place we’d be staying, Green Gulch in Marin County, just across the bay from San Francisco, looked like it might be just the ticket after a stressful initial year in a city comprised of 600 square miles of sprawl. Seclusion. No cell reception. No computers. Quiet.

It sounded, in other words, pretty damn zen.

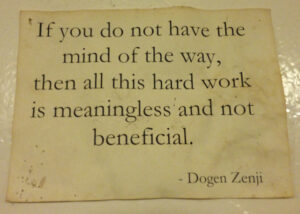

What I quickly found over the next few days was that Zen practice is not what I’d always assumed. Meditation is not a way to leave one’s body and mind behind, to slip off to some place of waking unconsciousness. Quite the opposite. It is a technique used to be hyper-present, to be aware of your breathing and the sensations tingling through your arms and the pain shooting through your ass and legs from sitting too long. It is about becoming undistractedly mindful of your self in this time and this space. In meditation you are not, as we so often are, physically in one place, but really elsewhere: back at work or school; reliving some conversation or looking ahead to another; fantasizing about people or experiences that have little to do with where we are at the moment.

Now, the truth is that I am not a practitioner of zen meditation. My brother, after that initial trip, has stuck with it. He meditates. He takes classes. He even spent three months this year back in San Francisco in an intensive practice program.

For me, it just didn’t take. But what stuck was the idea of mindfulness, of being present. I do try to be in the moment, to work when I am working, to rest when I am resting. And this simple idea has made a huge impact in nearly every aspect of my life.

So, my advice to young writers is this: quit thinking about your writing all the time. Look around you. Be present.

Here’s what you do: make a meal by yourself. You can cook for more people, but do the cooking alone. Find a recipe that looks good—nothing too elaborate, maybe a nice fresh pasta sauce or some kind of casserole—and get the ingredients from the grocery. Bring a radio into your kitchen and put on NPR or some quiet music that won’t be too distracting (save the Norwegian death metal for later), maybe Nina Simone or Chopin or Fleet Foxes. Pour yourself a glass of beer or wine or make a cup of tea. Preheat the oven. Start chopping ingredients. Take your time. Follow the recipe. Every once in a while take a sip of your drink. Don’t get drunk. And don’t think about that story/essay/poem waiting to be reworked. Just cook. Be aware of the sounds and smells rising in the kitchen. Feel how the knife goes through a tomato. Concentrate on the way your eyes burn from the onion. Don’t be discouraged if your dish comes out weird or even bad. Sometimes things just turn out weird.

Do this once a week. Your writing will improve.