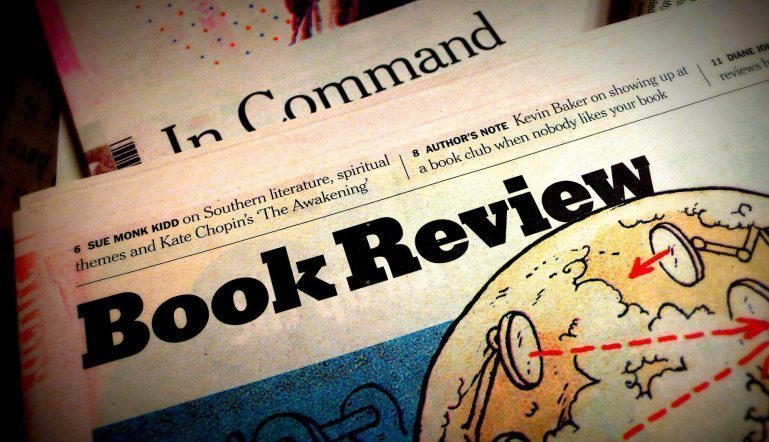

The Book Review in Review

The practices and ethics of reviewing poetry have recently reemerged as a hot-button issue in the literary community, especially in the wake of a plagiarism accusation in a review by William Logan and a particular “take-down” review of a first-book poet, both of which appeared in the same literary magazine in 2017. In particular, many writers have discussed the efficacy and aims of the “negative” review, how and if it impacts poetry and its readership in general beyond the immediate effects it has on the reviewed book and poet. For some, the idea of reviewing a book that one doesn’t like is antithetical to their ideal of community-building practices and literary citizenship. It takes up time and energy one could spend on supporting a poet and book one admires and, for them, silence suffices for a negative review, whereas others believe that critical examinations and even questioning of poetic craft is important to our art and the discourse surrounding it. The issue, however, is when a review, whether positive or negative, attempts to do something beyond assessing the work’s quality and positioning it into a literary and cultural context; reviewers cross the line when they make assumptions about a poet based on their work and/or when they make value judgments based exclusively on aesthetic, demographic, or other personal biases. Of course, no reviewer can be inherently objective, and poetry criticism should account for the reviewer’s subjectivity as long as that reviewer acknowledges their subjectivity, explicitly in the review or privately in their approach to the review, so that the potential readership experiences of others aren’t dismissed by the review’s assessment of a text.

Many reviewers don’t check their biases in the reviewing process, however, and many of the bias-based claims within reviews betray larger, more worrying issues of bias that are often masqueraded as “best practice” or touted as “just how things are.” In a recent piece published by The Atlantic, Megan Garber explores the rhetoric surrounding Kristen Roupenian’s short story “Cat Person,” which was apparently “so resonant with the current moment…that many people, receiving and then sharing the viral story on social media, seemed to interpret Roupenian’s work of short fiction not as fiction at all, but rather as a personal ‘essay’—a factory issue of the first-person industrial complex.” Garber uses this moment to discuss the tendency of many readers to read into women’s writing as autobiographical, even when the writers themselves declare their work fictional. Poets, of course, must often endure these assumptions about the “truthfulness” of their art. Once, after a reading, I had an audience member come up to me to ask deeply personal questions about a miscarriage, something that listener had assumed I’d experienced based off a poem I’d read. The projection of autobiography onto a work, in a review or outside it, is a form of textual violence, unless otherwise affirmed by the writer.

“Textual violence takes many forms,” Kristina Marie Darling writes in “Readerly Privilege and Textual Violence: An Ethics of Engagement” over on the Los Angeles Review of Books’s blog. Although the scope of Darling’s essay extends beyond the review into readership-at-large, from editors and mentors to readers and reviewers, her points about the ways in which readership can erase and even violate an author act as a compelling grounding imperative for readers and reviewers. She continues: “For me, the most egregious of these violations occurs when the reader makes inferences that extend beyond the work as it appears on the page….All too often, very personal essays, poems, and fiction become springboards for attacks that are largely personal in nature.” Here I would like to expand Darling’s notion of the personal. Although a personal attack could include judgments about the poet-as-person and/or insults guided by interpersonal beefs between poet and reviewer, it could also include judgments that, on the surface, seem craft-based but are actually the reviewer’s uninterrogated biases internalized because of the power and privilege dynamics within the institutions and communities that have historically been given the opportunities to write, read, and assess writing. Poet and critic Rachel Mennies has insisted upon the practice of “decentering,” which she describes as “explicitly interrogating my positionality to a text as a white reader before engaging in a critique—knowing when I’m not the person who should speak first/loudest about a work of art.” These biases might be based on race, gender, sexuality, class, regionality, citizenship status, aesthetic, etc. As a matter of practice, whenever I have a negative reaction to a book, I run through the following questions in my mind:

Is there some emotional context for which I and I alone am responsible that’s causing me to have negative feelings and reactions about this work? If so, this isn’t fair to the poet or the book, and I will make a point of returning to the work when that emotional context is no longer true.

How does the privilege I recognize I have as a white, cis woman mediate my experience of this poet’s concerns and craft choices? Sometimes I cannot answer this question, but the act of asking it has often humbled my opinions.

How has my previous reading experience, including the works I have read in my educational experience and through my personal choice, prepared or underprepared me for this work? Have I spent enough time deeply investigating with the literary traditions with which this book engages? If not, I need to get to work before I can touch this in a review.

These questions have helped me grow as a reviewer, even if I remain imperfect in negotiating all of the nuanced consequences of assessing a work critically and publicly. For personal reasons, I focus on writing generally positive reviews that allow for what I call criticism in the spirit of curiosity, as this allows me to engage purposefully in the kind of literary citizenship in which I want to participate. My ideal practice of book reviewing, of which I always fall short, is all about balance: I want to capture the book’s intended and executed work; describe my experience as a reader, with a projective eye toward those of potential readers; attempt to locate the poetry’s relationship to literary traditions (plural emphasized here, as there is no one literary tradition) and its relevance among contemporary movements; and recognize and work against the ways in which my experience of the book may be influenced by power- and privilege-based biases. This, I hope, gives an evocative impression of the book while honoring my readership experience and my reviewing goals.

Elisa Gabbert, in a recent entry into Electric Literature’s Blunt Instrument feature, says it best when she writes, “A piece of criticism should illustrate an engaged and considered approach to a book and, by extension, other books like it; it should demonstrate what good reading and good thinking about reading look like.”