The Chorus of There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis

To read There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis, out this month, is to plunge back into the summer of 2020. The collection, edited by two-term U.S. Poet Laureate—and former Ploughshares guest editor—Tracy K. Smith and Knopf executive editor—and former Literary Hub executive editor—John Freeman, documents this period of quarantine and protest, bewilderment and commitment, like a collaborative textual time capsule. The book is also like a map, depicting not just time, but place.

There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love gathers forty entries, many of them first published by Lit Hub in a series called “Letters Home.” These letters—and poems and essays—insistently locate themselves. They are written from, and at times written to, Miami and Seattle, Wisconsin and Texas, Hawai’i and Georgia, Sacramento and Minneapolis. Together they suggest a dispersed cloud of witnesses, an American representation not electoral but literary, the perspectives as inescapably political as they are personal.

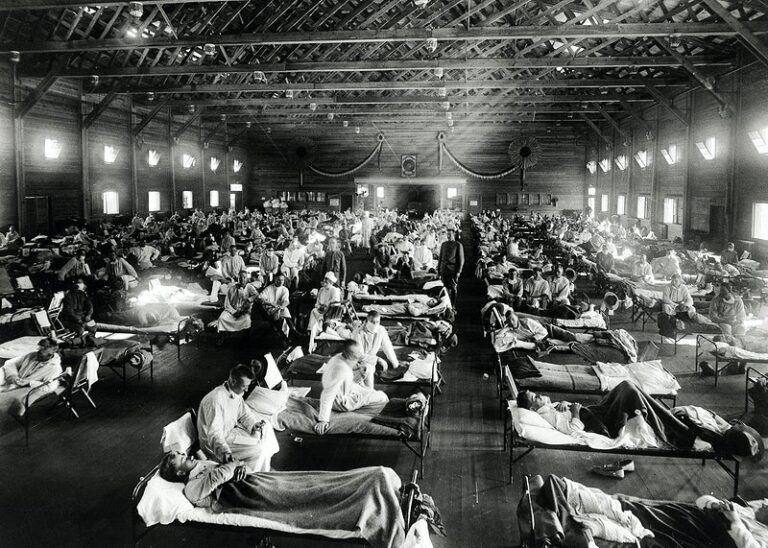

The contributors are poets, novelists, essayists, and journalists. They are Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, queer. As the book unfolds, certain resonances accrue. One of these is the pandemic’s fearsome mystery in its early months. Some of the collection’s entries read like unmetabolized trauma, raw personal reportage from the thick of it, reminding us of how little we knew just one year ago, how anxious we were about the upcoming fall presidential election, about COVID-19’s long-term threat. Edwidge Danticat, for example, writes of the sound of ambulances in her Miami neighborhood and the lost practices of communal mourning for a neighbor who has died. This is a refrain throughout the book: the background noise of ambulances and helicopters, the distanced funerals over screens. Others write of grocery shortages, shepherding children in shifts to online school, houses and apartments turned paradoxically to restrictive havens.

But for all its descriptions of sheltering in place, the collection’s missives focus less on the new dangers of COVID-19 than the all-too-familiar dangers of white supremacy, what Nikky Finney calls “the great malignancy of racism.” “America, there is not a place I can wander inside you / and not feel a little afraid,” writes Camille T. Dungy in her poem “This’ll Hurt Me More.” Dungy and others recount stories of racist violence in their childhoods, their adulthoods, their ancestral and communal memory so frequently that the stories—each inescapably particular and singular—swell into a chorus of lament. These recollections connect past to present and community to community, as in Layli Long Soldier’s piece “I Cannot Stop: A Response to the Murder of George Floyd,” which traces resonances among the endurance of the grandmothers after the Wounded Knee Massacre, the founding of the American Indian Movement in Minneapolis in 1973, and the poet’s own experience of police bullying on a trip to Standing Rock—all of which leads to an empathetic “poisonous dread” at the news of Floyd’s murder. In response, Long Soldier’s “elder instinct” instructs her “to write.” She does, exemplifying a cross-racial solidarity that threads through the book: Indigenous writers centering Black lives, Black writers acknowledging their presence on stolen Indigenous land, Asian writers like Su Hwang acknowledging both, as well as the reality of both anti-Asian prejudice and her Korean community’s complicity through “white adjacency.” “White supremacy does not allow for nuance,” Hwang notes. In contrast, the forty voices, with their forty perspectives, represented in this book refuse to back away from nuance, particularities that further underscore the points of repetition.

The forty voices bear witness to the ways the pandemic’s threats run through old channels of injustice. Time and again, contributors offer the damning statistics about Black, Brown, and Indigenous people’s disproportionate suffering from COVID-19 within their local and diasporic communities. Writing about Pacific Islanders, for example, Craig Santos Perez calls this phenomenon “colonial comorbidities.” Perez’s alliterative metaphor describes a material reality, and this is another strategy writers throughout the collection use: frequent images of struggling to find breath in the toxic air, for instance, bear witness to Eric Garner’s elevenfold “I can’t breathe.” In her poem “Three Liberties: Past, Present, Yet to Come,” Julia Alvarez adds to this image another devastating juxtaposition:

a virus of violence against

our darker brothers & sisters,

still marching, still unable

to breathe with knees

on their necks in our name—

8 minutes, 46 seconds:

time enough to wash our hands

of the matter 26 times.

Alvarez spins a lyric that begins with the speaker washing her hands in pandemic protocol into haunting commentary as she translates the length of the video documenting George Floyd’s death into twenty-second handwashing sessions—the choice between solidarity or bystander passivity.

Smith centers a similar question in her preface to the book, writing about how the summer of 2020 confronted Americans with a series of choices. Despite being “held in place at home alongside everyone else in America,” Smith writes that she “experienced the feeling of having come to a crossroads.” She moves her spatial metaphor into time, describing a pull between past and future and her sense that “we could move ahead into reconciliation and redress, or we could allow ourselves to be yanked back by our national denial of the ways systemic racism impoverishes us all, no matter who we are.” This urgent choice undergirds the whole book. Like a litany, the contributors repeat the names: Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and especially George Floyd, whose murder at the hands of a police officer on May 25, 2020, sparked what Smith calls in her preface “America’s most recent Freedom Summer.”

Many of the letters narrate participation in public action in this summer of protests, as writers like Pitchaya Sudbanthad and Ali Black describe how they tied their shoes, donned their masks, and took to the streets. Again, these accounts are often rooted in family and cultural histories of struggle in the United States and elsewhere, a thread of connection and motivation. “Though you’re a germaphobe and deathly scared of falling ill, you march anyway,” Daniel Peña writes. “Your family came to this country for this exact reason, for you to exercise these exact rights. And though you come with rage, you see how everyone around you has converted that rage to light. Everywhere there’s light.” The light emerges not just in protests on the street but also in accounts of mutual aid, voter protection efforts, and “collective organizing and acts of solidarity,” as in Keeanga-Yamahhta Taylor’s description of creative community efforts in Philadelphia to achieve “a future in which the country does not return to a long-forgotten normal.”

Many contributors also insist on the light of joy as its own mode of resistance. Michael Kleber-Diggs describes the lifesaving magic of Big Boi’s song “Chocolate” (feat. Troze) during the “disquieting days and violent nights of early June 2020” in his essay “On the Complex Flavors of Black Joy.” Ross Gay lauds basketball courts he’s loved, insisting on “a court as a site of care, ball as a practice of care, a kind of constant practice at working it out”—“You know, together. That’s the flight. That’s the beauty.” Samiya Bashir recounts how “this year threads its needle between robbery and gift, horror and beauty. Global trauma and lovely surprises.” Indigo Moor offers a powerful reclamation of William Carlos William’s famous wheelbarrow poem as depicting the poetry of Black life, in a sense answering Joshua Bennett’s question later in the collection, “When we turn to the written page, where is Black life lived? Anywhere. Everywhere.” Bennett goes on, “We conjure a world that is worthy of us. And then we gather there: unbowed, unburied, unabashed in our joy.” He ends his entry with a poem, “Benediction,” which across three pages rises toward its own exultant conclusion:

God bless the unkillable

interior bless the uprising

bless the rebellion bless

the overflow God

bless everything that survives

the fire

The fire dominates the book’s first two-thirds, with entries from the summer organized not chronologically but in thematic threads. Towards its end, contributions arrive from later in the year: many address the November 2020 election, and they tend to be longer and more thoroughly researched and reported. The change in form suggests a different urgency, not reports-from-here so much as analysis to guide readers through the likely chaos of election season. Reginald Dwayne Betts writes about Kamala Harris and mass incarceration, sussing out the “classic dilemma of Black people in this country: being simultaneously overpoliced and underprotected.” Monica Youn writes about threats to democratic elections, and Francisco Goldman draws on his connections to Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, and Argentina to write about the “aftereffects of an evil dictatorship” and the “steadfast struggle” required to achieve justice. The sense is forward-looking, an insistence that while the most recent Freedom Summer may give way to a new season, the work is ongoing.

And so it is fitting that the collection ends with gestures to both the ancestral past and the future generation. Sasha LaPointe offers the penultimate reflection, drawing lines between George Floyd’s murder, the COVID-19 pandemic, and her Coast Salish great-grandmother’s project commissioning a symphony threaded with spirit songs to offer the world the songs’ medicine. Writing of dancing on election night, “lost in a brief moment of hope,” she concludes, “we were trying to heal.” Kristen West Savali’s “On Motherhood and Ancestral Resistance” follows, the collection’s last piece; it is similarly bent on healing. In this letter to her son Walker, Savali joins many of the book’s contributors focusing on their fears and hopes for their children—earlier, Idrissa Simmonds-Nastili unforgettably insists, “I am a black mother living in America. You cannot blame me for wanting to watch my child breathe all night.” Savali’s piece takes up these thematic threads as she names both the “unfathomable grief” and also the sustaining “grit, wisdom, and determination of our Mississippi ancestors.” Recounting racist violence new and old, Savali offers the book its title phrase as she seeks to situate what’s happening as she writes, on August 6, 2020, within familial and broader histories. The reflections lead to the heartrending question, “Where in the world is safe for you, my beautiful, beautiful boy?”

“There’s a revolution outside, my love,” she repeats. “And as empires and tears fall, you need to know that you come from a tradition of Mississippi warriors who have resisted despair’s siren song and remixed it until it sounded like freedom.” And if and when the grief arrives for her son, she writes, “I promise you this: You will see your pain in others, as I see my pain in you. You will see your power in others, as I see my power in you”—“I will fight for your joy and your freedom all the days of my life.”

Savali’s achingly tender words, coming after nearly three hundred pages of inescapably particular reflections, offer a rubric for the project as a whole. Over the pages, the resonances build like voices gathered in a street singing justice songs, an effect that would be impossible to achieve without the book’s many-authored form. For those already gathered in the work, the many-voiced chorus offers solace, solidarity on the long road. For those who haven’t joined in yet, Savali’s words issue a call: Will you join the fight for Black joy and freedom? Will you listen to these stories, and will you let them move you? Will you let yourself see your pain and your power in their voices? Will you join the chorus lifted in these pages, join the bodies gathered in the streets?

This piece was originally published on May 24, 2021.