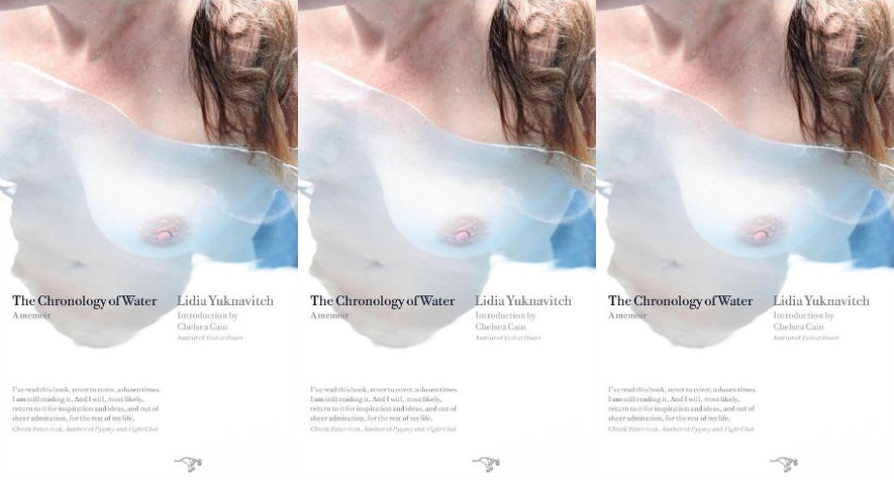

The Chronology of Water

The Chronology of Water

Lidia Yuknavitch

Hawthorne Books, April 2011

268 pages

$15.95

“Little tragedies are difficult to keep straight,” writes Lidia Yuknavitch in The Chronology of Water. “They swell and dive in and out in great sinkholes in the brain.” The loss of her daughter, stillborn, is precisely that kind of tragedy, and launches Yuknavitch’s nonlinear memoir that is at times lyrical, at times conversational, and almost always intense.

Carefully arranged in their nonlinearity, five chapters—Holding Breath, Under Blue, The Wet, Resuscitations, and The Other Side of Drowning—each comprised of shorter titled sections, engage the reader with profound emotions: grief, rage, passion, a desperate need for numbness, and “purity of happiness.” Sometimes Yuknavitch prefaces a difficult moment by telling readers that we’ll get it “straight no chaser”; other times she leads us down a garden path, seducing us with something romanticized, mythic (mythic and epic being two words that repeat throughout the book), only to stop abruptly: “OK that’s a big fat lie,” she’ll write. The story is more complicated, and she doesn’t try to smooth over those complications or make them fit into expectations of mainstream memoir.

Growing up with an abusive father and an alcoholic, suicidal mother (parents she takes pains to write about, in later sections, with great compassion), Yuknavitch immerses herself in swimming, her mode of survival. An athletic scholarship to Texas Tech gets her out of the house, but, addicted to drugs and alcohol, she loses it. “I wanted to eat all the colors to get to the not feel,” she writes. The “not feel” comes through substances, copious sex with men and women, and close encounters with death—car accidents, a cracked skull—all interrupted, at least temporarily, by the conception of her daughter and a move to Oregon to reunite with her older sister.

Ultimately Yuknavitch is interested in the “body stories” we all have. While references to her father’s abuse remain elliptical, intensifying the terror of what’s unsaid, she tells the story of her own body in precise, gutsy detail. Squeamish readers may resist some sections (one, for example, describes S&M), but her candor is admirable.

And despite all the book’s little tragedies, it’s a joy to see Yuknavitch’s writing, teaching, and publishing careers flourish, and then to see her husband and son swim with her towards “rebirth.” “You were never, in the end, alone,” she writes, in Resuscitations. “Isn’t it a blessing, what becomes from inside the alone.”

Anca Szilágyi is a Brooklynite living in Seattle. Her stories have appeared in publications such as The Massachusetts Review, Western Humanities Review, and The Antigonish Review. Recently, she earned an MFA from the University of Washington, where she has also taught short story writing and co-curated the Castalia Reading Series. She is revising her first novel.