The Countryside as Escape Button

It’s a trope as old as any: someone, usually a man, gets fed up with the oppression of the everyday routine and the shackles of society and/or responsibilities, so they walk out, leaving behind their life, or job, or family. Or all of the above. Sometimes it’s selfish, sometimes justified, often the story smacks of sexist expectations—who gets to go have adventures and who is expected to take care of the kids.

And where do these characters escape from the everyday life to? More often than not, it’s outside of civilization, past the city limits, to the countryside. It’s portrayed as a move to something freer and simpler, getting closer to some kind of essential experience of living. This could mean a test of survival versus nature, à la Into the Wild or just Wild. Or it could be a Thoreau-sian purification via isolation and manual labor.

At the end of this story might lie a, possibly unearned, heartfelt homecoming.

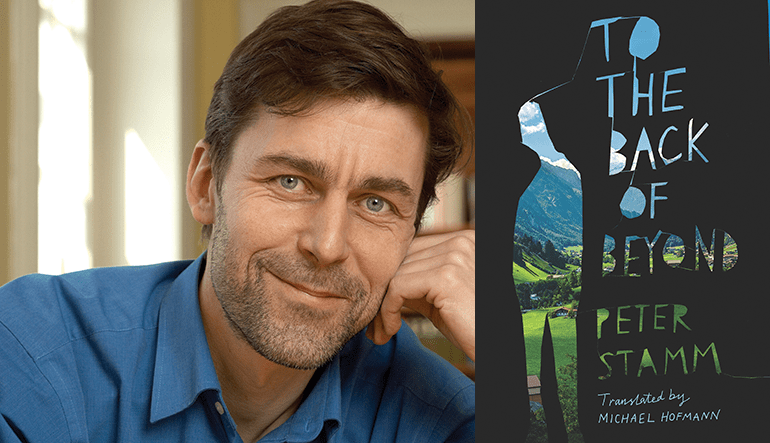

To the Back of Beyond, Swiss writer Peter Stamm’s latest novel (tr. Michael Hofmann), starts off in this well-trodden vein. Thomas and Astrid have recently returned to their small home in a Swiss village from a vacation to Spain. They sit on a bench outside their home, drinking wine and reading the paper, when Astrid steps inside to address a sleep-defying child. Instinctively, Thomas rises, walks out of their yard, and doesn’t return.

But like any skilled writing digging into a trope, To the Back of Beyond quickly veers away from expectations. Thomas does not appear to be unhappy with his life. He’s clearly in love with his wife and displays no animosity to his job. And while he moves closer to nature as he walks, his life didn’t seem to be that far from it before. He and his family lived in a small town, and the Swiss mountainsides he ends up on are not far from his house at all.

There is no real logic expressed to Thomas’s actions, seemingly because Thomas himself cannot articulate his motivation. But Stamm is very good about evoking an ineffable internality through the details he points the lens of the character towards or the memories that show up. When Thomas leaves his yard, he “lifted the gate as he opened it, so that it didn’t squeak, as he had done from when he was a boy, coming home late from a party, so as not to wake his parents.” Guilt by association, or just an expectation of guilt. The snippets of thoughts we get from him about his life offer fleeting insight and more questions. He loves his wife but feels closest to her “at moments of uncertainty, of crisis and quarrel.” When he thinks of their house, his description of it is that it “was slowly falling down, imperceptibly but unstoppably.” This is followed by a more elucidating observation: “He had read somewhere that a building wasn’t finished until it had collapsed into ruins. Perhaps the same was true for human beings.”

As to his actual journey away from that house, we see almost none of his thoughts. There’s something primal about his actions: he automatically hides from cars and people without thinking, he has no qualms about breaking into buildings for shelter and food, and one of the few expressed emotions is when he feels “freer than before” after spending the last of his money. This primacy is rooted in an annoying and selfish masculinity, but it also lends an element of surprise to the story. We’re never sure what Thomas will or won’t do next.

Sections of the book are from the perspective of the left-behind Astrid. While her husband runs from routine, she finds comfort in it, first through the caring of their children and then through the methodical and delayed dealing with her husband’s disappearance. She wants to be furious with Thomas but instead worries about him, misses him. Though she is confined in ways Thomas is not, she still evokes agency and claims a form of freedom in her imaginings of what is happening to Thomas. These imaginings build throughout the novel and blur the line both for Astrid and for the reader between the real and the imagined.

In the opening chapter of White Teeth, Zadie Smith writes that, “Generally, women can’t do this, but men retain the ancient ability to leave a family and a past. They just unhook themselves, like removing a fake beard, and skulk discreetly back into society, changed men. Unrecognizable.” As Smith suggests, the need to run away from routine and familial responsibilities to achieve some sort of hazy simplicity is typically ascribed to men, and that makes part of Stamm’s work here disappointingly familiar. But the book does move past that, through flashes of beautifully rendered observations, turning a cliché escape into something both ethereal and lucid, with just enough surprise and wonder.