The Creation, Innovation, and Evolution of Early Anti-Racism Writing

Black writers have for centuries used literary conventions as a means to craft their arguments towards their own liberation, making anti-racism writing as old as America itself. Slave narratives in particular, a genre of nonfiction that grew out of the early novel, represent a literary form that allowed writers to argue for the abolishment of American chattel slavery. With the establishment of this new type of writing, the slave narrative became a subset of stylized nonfiction meant to combat white supremacist structures by articulating the first-person experiences of enslaved Africans and Black Americans. It’s a radical genre often overlooked, as well as the beginning of a distinctive literary tradition.

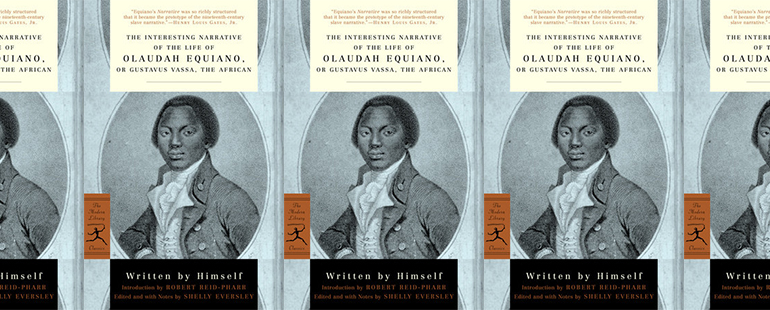

Olaudah Equiano’s early slave narrative, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African, published in 1789, is a genre-defining work that was a distinctly new form of hybrid literature upon its release. In The Signifying Monkey (1988), Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes about Equiano’s narrative, saying, “It was Equiano whose text served to create a model that other ex-slaves would imitate . . . Equiano’s strategies of self presentation and rhetorical representation heavily informed, if not determined, the shape of Black narrative before 1865.” Equiano’s work, which created a road map for other Black authors, is a memoir constructed of a blending of genre ideas that were developed during a time when the novel had only begun to emerge. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is at once an adventure novel, bildungsroman, and a conversion story. Each of these forms and craft decisions contributes to Equiano’s arguments for the abolishment of slavery, and his creation of this literary framework is the origin to which today’s anti-racism writing can be traced.

Equiano published his narrative in 1798, not even fifty years after Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740), considered by many to be the first novel written in English. The form was thus quite new while Equiano began welding together ideas and plots from novels to craft his hybrid memoir. By adapting the traits from popular novels of the day, Equiano’s narrative centers his experience and makes himself the story’s main character, though his adventures often hint at themes of divine intervention and fate. As he wrote, two early novels may have stuck out to him, both because of their popularity, but also because of how their authors portray their heroes.

Aphra Behn’s Oronooko (1688), a sweeping portrayal of West Indies chattel slavery, was one of the first works of British fiction to try to conceptualize slavery. Behn’s account of an African prince, Oroonoko, and his love, Imoinda, who are enslaved in the West Indies is romanticized, but it also attempts to understand Africans, their society, and slavery in British colonies. After a failed slave revolt, the early novel ends with Oroonoko and Imoinda’s tragic deaths as they attempt to preserve their honor. Oroonoko’s status as a Prince and a heroic warrior, however, is recognized even in slavery by his captors, who give him the slave name Caeser. Equiano’s narrative of his personal experience with slavery likely came at odds with Behn’s exoticized ideas, but his memoir is similarly full of discussion of destiny, inheritance, and the place for African heroes in a racist system.

Equiano’s narrative is similar aesthetically, too, to novels of the time, with its fantastical account of adventure and survival. Reminiscent of William Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), the text is colored with episodes of shipwrecks, naval battles, and kidnappings. Equiano’s experiences as an enslaved and later freed African man, traveling through the Caribbean, into America, and later to England, are crafted as adventures. Fittingly, though he mimics the form of an adventure novel, he ultimately withholds the conclusion a hero deserves. As both a free and enslaved African, Equiano struggles to find a place where he earns the respect of white society. Using concepts from Defoe’s popular adventure novel and Behn’s ideas about new worlds and slavery, however, Equiano makes himself a main character who is clearly identified to readers as the hero of his text, even when a racist society doesn’t recognize him as such because of his race.

Like Behn’s Oroonoko, Equiano’s text offers readers a novelistic presentation of his own coming of age as an African prince in a racist world. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano follows, in many ways, the classic structure of a bildungsroman, and is interested in themes of maturity, fate, and inheritance. Equiano first provides a detailed rendering of life in Africa and the society he was born into, The Kingdom of Benin. He writes:

My father was one of those elders or chiefs I have spoken of, and was styled Embrenche; a term, as I remember, importing the highest distinction, and signifying in our language a mark of grandeur. This mark is conferred on the person entitled to it, by cutting the skin across at the top of the forehead . . . . Most of the judges and senators were thus marked; my father had long born it: I had seen it conferred on one of my brothers, and I was also destined to receive it by my parents.

Equiano makes clear he is born into a ruling family, in a culturally rich society that he refers to as a “nation of dancers, musicians, and poets,” and in which he himself is destined to inherit an important role. Though his inheritance of becoming an African ruler is interrupted when he is kidnapped and sold as a slave, the uniqueness of his destiny does not end. Instead, it morphs, in part because of the important role he takes on as a storyteller—a responsibility that is in line with similar roles in the Kingdom of Berain. His storytelling, however, doesn’t follow an oral tradition like the one he was born into, but instead a literary one, as a writer of his own experience. Equiano’s fate changes under the structures of white supremacy, but he is not stripped of his birthright.

With his eventual conversion to Christianity, Equiano is able to offer a religious frame to the injustice he sees while enslaved, and how he and other Black individuals are treated under an unequal society. Equiano’s newfound religiosity allows him to survive a shipwreck, having been foretold of the disaster in dreams like the Biblical figure Joseph, whose dreams helped him escape slavery in Egypt in Genesis. On a ship heading towards Belle-Isle, Equiano writes, “Every extraordinary escape, or signal deliverance, either of myself or others, I looked upon to be affected by the interposition of Providence. We had not been above ten days at sea before an incident of this kind happened.” While all the white men on the ship are drunk, Equiano, having been warned in dreams and given up drinking to become a better Christian, is able to evacuate the ship, saving everyone. Equiano feels chosen by God, even over white men who have more power than him.

Equiano connecting himself to a prophetic dream tradition aligns him with a rich Biblical history of God choosing particular figures to communicate his will who follow through using incredible action. Equiano being set apart in this way speaks to his importance as the protagonist of his narrative. God’s wanting to choose an African man to pursue heroic, providential actions speaks against the racial divisions of slavery. If God is choosing a Black man to save a ship instead of the white men aboard it, who are lazy and drunk, Equiano is suggesting that the Black man is just as acceptable as the white man. By using dreams as a method of communication between himself and the divine, Equiano stages himself as a significant protagonist with an important destiny. He also effectively calls upon his audience’s religious tradition, which therefore demands the attention of his readers.

Equiano’s narrative is focused on showing how society doesn’t allow his character to prosper, even though he completes heroic actions, has a divine birthright, and has converted to the Christian faith. Many times Equiano’s money is taken from him or he is cheated in other ways, but because he is Black, he is unable to find justice. His narrative clearly aligns itself with a tradition of anti-racism writing when he says, “The punishments of the slaves on every trifling occasion are so frequent, and so well known, together with the different instruments with which they are tortured, that it cannot any longer afford novelty to recite them; and they are too shocking to yield delight either to the writer or the reader.” In his slave narrative, Equiano creates a vehicle through multiple genre tropes borrowed from novels that grab his reader’s attention, all of which compose a frame through which he argues against the eradication of white supremacist structures. His adventure novel demonstrates that he’s a hero who is never rewarded for his bravery. His bildungsroman shows his journey to achieve his rightful destiny, which is constantly out of reach in a racist world. His conversion story proves that Christian virtue doesn’t automatically allow him to find a respected reputation among white society, even when recognized by God.

The slave narrative genre created by Equiano has been built upon by numerous Black authors, including William Grimes, Solomon Northrup, Frederic Douglass, and Harriet Jacobs. Such works are as much a means of arguing for racial justice as they are a way for Black authors to carve out space in the nonfiction genre for themselves. It’s a shallow reading that sees slave narratives as works where their Black authors are portrayed as victims, perhaps even perfect victims. In a closer reading of these narratives, which understands the use of literary convention, the innovation of Black writers, portraying their realities within a constraining genre form, is clear: slave narratives use structures and tropes to portray the effects of racist structures on individuals’ lives, argue for their humanity, and demand their liberation in an undeniable, effective, and brilliantly-rendered way.