The Discomfort and Difficulty of Attention

In what is the most well-known scene from the 2017 film Lady Bird, Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson and her teacher, Sister Sarah Joan, discuss attention. Reviewing Lady Bird’s college admissions essay, Sarah Joan notes that Lady Bird clearly loves her hometown of Sacramento because she writes about it “with such care.” Lady Bird, skeptical, downplays it as “description”—just “paying attention”—to which Sarah Joan replies: “Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?”

It’s a profound and difficult question, which is perhaps why Sarah Joan frames it so gently (“don’t you think,” “maybe”). And it sounds comforting initially. To love something, someone, is to pay attention. To use the language of twentieth-century philosopher Simone Weil, to pay attention is to approach others with a fundamental generosity.

But such attention is more uncomfortable than it sounds. As the film (and Weil) suggest, attention is hard. It requires us to recognize the pain and inequity in the world around us, and it is characterized by waiting and silence. “Let’s just sit with what we heard,” Lady Bird’s mother, Marion, asks at the start of the film, as she and her daughter cry in the car while listening to the audiotaped conclusion of The Grapes of Wrath. But Lady Bird can’t just sit. She wants the radio on, starts a fight (which her mother eagerly joins), and eventually throws herself out of the car all to escape the waiting silence of attention—of sitting with what she’s heard, of sitting with her mother and their loving (and fraught) relationship, of sitting with her life in Sacramento.

Attention’s discomfort and difficulty is only amplified by the ways that attention itself seems fundamentally incompatible with modernity. Several studies paint a picture of attention as increasingly countercultural, perpetually in crisis. Even if we want to pay attention, can we? Can we stand to live a life of attention when that means having to recognize the painful world we live in? Can we bear to pay attention if it means more waiting?

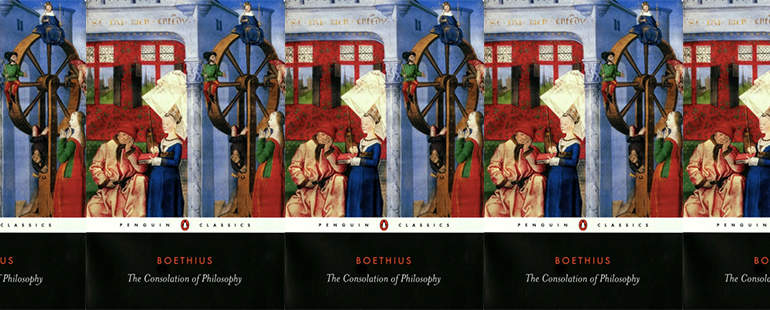

A history of attention holds little comfort but shows us that this crisis is nothing new. That from the very first attention has been characterized by discomfort, waiting, and painful recognition. We can see as much in the Oxford English Dictionary’s first recorded use of the word in English. It appears in a translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, likely written by Geoffrey Chaucer, from the late fourteenth century: “Aftir this sche stynte a lytel; and after that sche hadde ygadrede by atempre stillenesse myn attencioun, sche seyde thus . . .” (After this she stopped a little; and after she had gathered by a restrained stillness my attention, she said thus . . .). Fittingly, attention makes its first appearance in a fleeting and unremarkable moment of transition. It’s easy to miss, caught between one speech and the next, waiting in the pause between what has just been spoken and what will come.

The she of the quote refers to the allegorical figure Lady Philosophy. She serves as both guide and chastisement to author/narrator Boethius as he struggles to understand his unjust imprisonment and imminent execution at the hands of a tyrannical government in the sixth-century Western Roman Empire. Philosophy has just recited a poem warning Boethius that in his despair, even in his hope, over his unjust imprisonment, his judgment has been obscured: “For cloudy and derk is thilke thoght, and bownde with bridelis, where as thise thynges reignen” (For cloudy and dark are these thoughts, and bound with bridles, so that these things reign). These passions have made it difficult for him to see his life and the world accurately. It is here that we return to our transitional pause. She “stynte,” stops, for a while, and she forces Boethius’s attention to gather together through an “atempre,” restrained or modest, “stillenesse.” It is only once he has endured this silent stillness and his attention is on her that he and Philosophy can begin the long labor of unclouding Boethius’s judgment.

That attention is a necessary precursor to the difficult work of seeing the world clearly is evident in the text—Lady Philosophy will only begin when she has Boethius’s attention—but particularly interesting is the way that Chaucer’s use of attention represents a brilliant act of translation, simultaneously drawing together attention’s etymology and theorizing attention as an act of waiting discomfort and painful recognition that takes us back to what is so difficult about Sister Sarah Joan’s question.

The Latin original of Boethius’s text uses the noun attentio, which describes a state of attentiveness. Etymologically, this word derives from the verb adtendere, meaning “to stretch toward something”—as a person would stretch a bow. Medieval French maintained this connection in the verb atendre, with the additional connotation of “to wait for something.” Chaucer pulls these etymologies together. Attention occupies a space of stretching toward and of waiting. The passage holds Boethius and the reader in a place of suspension, making him and they await Lady Philosophy’s next words. It is also painful. Boethius’s reward for paying attention is the hard consolation of learning how to uncloud his judgment and confront his imprisonment and coming death.

After Chaucer’s translation of the Consolation, there’s a gap in English writing on attention. We see it next at the end of the sixteenth century. “O, but they say the tongues of dying men / Enforce attention like deep harmony,” remarks the dying John of Gaunt in Shakespeare’s Richard II. Lucrece tells her story of violent rape to her husband and his fellow lords who listen with “sad attention” in The Rape of Lucrece. Some seventy years later, Milton says of the fallen angels in Paradise Lost that “attention held them mute” as they await the speech of Lucifer. Across these vastly different texts, attention maintains its complex relationship to silence, waiting, and witness. In its evolution as a term, attention only grows closer to its etymological roots: to wait (atendre), and to draw toward (adtendre). John of Gaunt suggests that death draws men’s attention towards itself; Lucrece’s testimony pulls in the sad attention of her witnesses; the rebel Lucifer waits in a silence that makes his fellow fallen angels anticipate his words.

Pulling this early history close when we listen to Sister Sarah Joan’s question—“Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?”—we can understand the sheer difficulty of this formulation. What does it mean for love and attention to be the same?

I keep asking myself that question. Following attention back to its early history, it seems that part of the answer is to understand the sheer challenge of attention (and, yes, of love). To pay attention has an actual cost. It requires us to trace the brittle edges of our connections to other people. To witness their pain and have them witness ours; to wait and gather ourselves together to hear what’s coming next. What’s striking then is not only how completely comprehensible it is that attention is always in crisis, characterized as it is by silence, waiting, and recognition, but how absolutely necessary it is. Attention is the word that reminds us of the painful reality of existence—to always be waiting and inextricably stretching outward to see and be seen. A necessary challenge for the year ahead.

This piece was originally published on March 10, 2021.