The End of January: Suicide and Rape in Nothing Holds Back the Night

“My mother was blue, a pale blue mixed with the colour of ashes.”

Delphine de Vigan discovers her mother’s body on the first page of her autobiographical novel Nothing Holds Back the Night, and the opening line’s intensity endures. Considering Lucile on her bed, de Vigan asks “how did my brain manage to keep the perception of my mother’s body at such a distance, especially its smell?,” and the pages that follow are an attempt to breach this distance–not only the immediate perceptive distance in her mother’s bedroom, but previous cavities in understanding that time has seen grow deep and tender.

“And then, like dozens of authors before me, I attempted to write my mother.”

A slippery work in terms of genre, auto-fiction seems applicable as far process is concerned; de Vigan has not produced a novel based on her mother, but a work that enfolds the inevitability of fiction in its rendering. In filling in various lacunae, in writing into absence and through opacity, she must suppose, reconsider and supplant, and it is here that fiction–albeit deeply informed by reality–occurs.

De Vigan conducts extensive interviews with Lucile’s living siblings (they were a family of nine brothers and sisters) and there are certain points on which they all agree. Perhaps most pressingly, Lucile was exposed to the “possibility of death […] just before she turned eight.” During their summer holidays, her little brother Antonin falls down a well and dies. Lucile hears her young siblings’ panicked shouts, and the prose lingers in her psychology, in the unfolding of this first “foundational event”: “She waited a few more seconds before getting up. Something had happened, she realised. Something that could not be fixed.”

This early awareness that at any moment the irreparable may occur is the first of several fault lines that will later beg fracture.

Some years after Antonin, Jean-Marc, Lucile’s adopted brother, dies during autoerotic asphyxiation. The “official version” told his siblings, however–that as a battered child Jean Marc “was in the habit of protecting his head as he went to sleep,” and had died accidentally–seems incongruous to them. Left to wonder “Can you fall asleep at the age of almost fifteen with a plastic bag on your head without […] having chosen to?,” they deduct that their brother has taken his own life, and so suicide is anachronistically introduced into the familial fabric. Later, it will move through the siblings as a kind of blight.

Describing the family’s extended “suicide period” that will only culminate with Lucile’s death, de Vigan makes clear she’s uninterested in “psychogenealogy […] in phenomena transmitted from one generation to another,” stating simply that “incest, child mortality, suicide, madness […] run all the way through families like pitiless curses, leaving imprints which resist time and denial.” Whatever the genetic imprint, it’s clear that this lapse in knowledge around Jean-Marc’s death leaves Lucile with the entirety of her adolescent and adult life to consider the act and concept of suicide.

But the untimely loss of her siblings is not the only contributors to the depression and addiction that culminate in Lucile’s taking her life. Lucile, we read, doesn’t embrace her daughter after she turns ten, and this want of touch runs alongside the attention of a father who was too close, whose touch was harmful and excessive. After almost 200 pages of allusion to de Vigan’s grandfather’s domineering presence and physicality, we learn that, when Lucile was thirty two, she wrote a letter to her family:

We are off to our house in the country. I am with my lover, we are with my father.

[…]

That night I can’t sleep, I feel hunted […] I get up for a pee, my father is watching me, he gives me a sleeping pill and he drags me into his bed.

He raped me while I was asleep, I was sixteen, I have said it.

Chillingly, de Vigan writes “It was not long before Lucile realised what a mistake she had made.”

The accusation of rape, which is followed with present day recollections from other women who were either pursued or victimised by Georges, is systematically ignored by her whole family. The damage done by the assault itself as well as the insidious trauma of speaking a secret long kept only to swallow it back down, is compounded by Lucile’s being institutionalised shortly thereafter. De Vigan writes “The end of January still represents a sort of danger period for me (I discovered Lucile’s body on 30 January). It’s something which is rooted in my body.”

Of painting his mother, Lucian Freud said that he could only spend close, studious time with her once she’d “stopped caring”; bereaved of her husband and on the other side of a failed suicide, life was entirely blanched for her, and thus unaffected by the world Freud felt he could finally take her as a subject. De Vigan’s study is likewise governed by affect, but it is a series of affects that both constituted and destroyed her mother throughout her life. In tracing those “foundational events” which formed “a fault line, or […] an indelible imprint,” the present day loss of her mother to suicide is entwined with the childhood loss of a maternal-figure, and de Vigan looks to recover not only Lucile as a mother, but Lucile as a person who moved through life with cracks run through her.

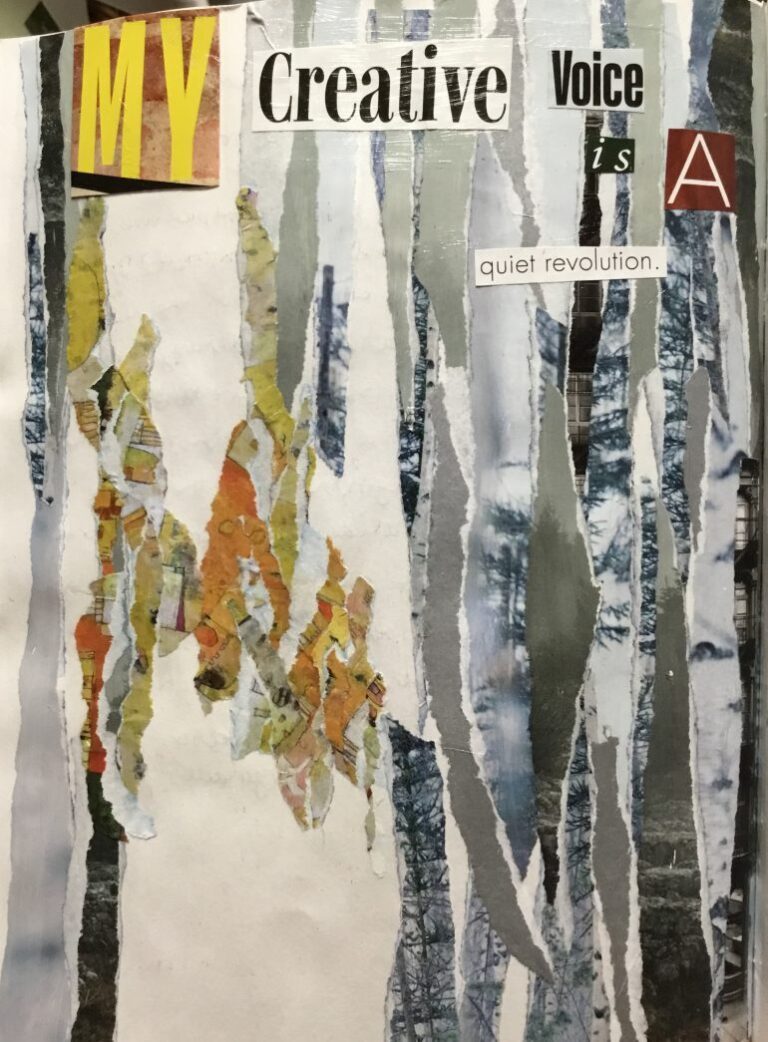

Though de Vigan writes with the knowledge that a truly faithful portrait is impossible, she seems to also write with the conviction that if a fraction of Lucile is to be glimpsed, the whole of her must be reached for. Ultimately, while she makes no claim that these instances of breach and fracture will ever fully coalesce in “explaining” her mother’s death, placed alongside one another they do suggest an outcome of sorts for the author in understanding the “destruction of [Lucile’s] self”; “Juxtaposition is to writing what collage is to images. The way I write these sentences, the way I place them, reveals my truth. It is mine alone.”