The End of Love is a Thing of Ugly Brilliance

A bus ride is not the ideal place to fall out of love. There are, in fact, myriad examples in film of people meeting their soulmates on bus rides. But years ago, almost a decade into a relationship, I was on a bus somewhere between Entebbe and Kampala with two dozen women from across the world when I began to turn my life of partnered bliss on its head. The women and I were on our way to a book reading. Someone had suggested that we pass the time it would take to travel between the two Ugandan cities sharing our love stories. I looked on from the sidelines of this activity, suspicious and curious, preferring mostly to study the passing scene of roadside furniture shops.

The signs that reveal the end of any love story are crucial. Denouements depend on them. In that chimera of a bus ride, I must have said something nice about my partner. But I cannot recall this now. In those moments, I was seeing, for the first time, the outline of every love I was missing out on.

Long-term relationships, no matter how worn out their mechanisms are, take their time to unravel. Or I am simply the kind of woman who takes her time leaving lovers. Either way, instead of seeking brevity and a complete excision from this long-term lover after I returned from Uganda, I reinserted myself into the routines of the life I shared with this man. A self-respecting masochist will very easily admit that committing to the slow burn of baggage is its own kind of arcane pleasure. I wanted the acreage of pain, real and perceived misdeeds, all of that old and tedious business that defines the end of love.

Yet, in spite of my desire to lean into agony, I continued to seek out possibilities for escape. I thought about making oblique, reflective threads on Twitter or traveling to a place with passable stretches of blue water and white sand to practice self-care. In the end, unable to follow through with any of these, I let myself fall into curious habits. I spent endless hours hunting down recycled internet pick-me-ups, screenshotting my way through the classics rabbit-holed deep within the recesses of the infinite scroll. I watched my camera roll fill up with minimalist reproductions of digestible Insta-quotes: You are gold baby, solid gold. But the questions remained.

How did one let go of the churning compost of moments shared with a lover? These internal things that keep bobbing up to the surface at the speed of memory? If there was any holy grail for mediating the end of love, I was ready to turn my back on the clusterfunk that is social media self-administered therapy to seek it.

Then, one morning I found a Ted Kooser poem on Tumblr, Pocket Poem.

In the ways that writers’ names get passed around, somehow, Kooser had never come up in conversations. The why of this is complex and rooted in conversations about the structural divides that determine how writers cross cultures and geographies. But in that moment, Kooser’s words were what I needed. I leaned into the comforts of this poem to find my motions of disremembering: “Midnight says / the little gifts of loneliness come wrapped / by nervous fingers. What I wanted this / to say was that I want to be so close / that when you find it, it is warm from me.”

The “I” in Kooser’s poem was caught in a moment of existential stasis that did not quite fit mine, but there it was: a tender intervention. The idea of the poem as the pause. What Mary Ruefle calls the “living semicolon.” There it was, a language for love as it turns. This poem, what it loosened in me—a hunger for words—led me to a Wislawa Szymborska poem I had not thought about for years, “Clouds.” In this poem, Szymborska reveals paradise as the act of passing through one’s own life and stopping to see. “I’d have to be really quick / to describe clouds— / a split second’s enough / for them to start being something else.”

There is a connection between footbridges and how people learn to fashion emotional connections as they let old love go. The idea that a decent footbridge needs to fulfill its function with iconicity and rationality is, I think, valid for the socially sanctioned conduits that carry us from the end of a relationship to the points at which we break even. I did not necessarily need my break even to be iconic, but at the very least I hoped for something rational.

In the weeks after I finally said goodbye to this lover, on YouTube I watched the American rapper, essayist, and poet Dessa explain to a transfixed audience the very complex neuroscientific procedure she had undergone to excise a fixation with her on-and-off lover after she had tried without success to let go. Surrendering her body to science, she had scanned her brain to find the neural correlates of love—a musical phrase for describing the parts of one’s brain where love is housed. And in looking at this scan as visual evidence of her irrational self, what she now calls a postcard of feeling, she had finally found some control.

But this idea of letting go as something drastic, as a form of self-immolation, is not new in itself. In Dessa’s submission, it had simply found new praxis. The extremes where people are expected to go when it comes to the excision of emotions between lovers have always bordered on melodrama. In one of her many letters to Boris Pasternak with whom she nurtured an unconsummated long-distance affair, the Russian poet Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva writes in 1926, after the dissolution of a side affair, “Dear one, tear out the heart that is full of me. Don’t torture yourself.”

Each generation will define the economy of love and intimacy in its own way, and in truth, I would have tried neurology if that option was open to me. But far more accessible than neurology and far less stark than Tsvetaeva’s admonition, I settled for a life of hookups, working my way through a small colony of lovers, men and women.

Perhaps more than any other generation before it, this generation firmly believes in the philosophy of sleeping one’s way out of a breakup. Finally a true compatriot, I was ready to experience a full spectrum of intimacies.

A new relationship, I decided, was ultimately untenable. While I had one, it served its purpose. It had been a better way to keep a log of my ethos. A thing of value on days when I was deeply fascinated with an idea and in need of a person to share it with. In this fundamental way, it had held up in diametrical opposition to other forms of intimacy for which any kind of sharing that might signify continuity or attachment is the deadly sin. And for this reason, I worried that I would miss it. But I expected to finally be unmoored from the smallness of a couch in which I had spent countless evenings willfully reclined next to my partner passing time and instituting monogamy.

What would it look like to live outside conventional yearning in this way? In popular culture, the classic hookup is depicted as a wonky Venn diagram of emotions and needs. It is all very hypothetical. An extreme sport that seems to posit: what happens if you draw an intimate circle around yourself and a random person and it’s too wide? What changes if you draw another and it’s too small?

Finally, you draw a circle, and it’s the weird shape that fits in its definition of this thing that is both desire and/or friendship but not quite love, affection, or an inexplicable need to belong to the other person. And to not know why the one person feels on the verge of falling out of this circle when the other reclines into the comfort and indeterminacy of the arrangement is what it is: a constant shock to the system. Or a wild way to live. But essentially unremarkable for being the zeitgeist. Viewed this way, it is all very exhausting, even for the self-proclaimed millennial savage.

Perhaps these depictions of hooking up are valid, but the imaged equivalent I have come to think of as representative of an intimacy that exists outside of monogamy is the husband and wife diptych from Toyin Ojih Odutola’s To Wander Determined.

Odutola’s depiction is of a marriage, strictly. But this painting is intentional in its offering: an unsentimental suggestion of the estrangement inherent in all intimacy. Of her attraction to this type of portraiture, Odutola has said in the past that she is interested in the act of playing with perception, what you think you are seeing. And in this painting, a man and a woman look in opposite directions. It is impossible to tell if they have just turned from each other momentarily to attend to present distractions or if they are in fact walking away from each other.

The diptych is part of a series of interconnected depictions of aristocratic living among two Nigerian elite families connected by marriage. Part fiction, part factual. The title of the series itself—To Wander Determined—examines ideas of migration and dislocation, but the artist invites us to loose associations and interpretations in her imagination of fantastical landscapes for the body of work to which this painting belongs. And so, in negotiating the terrain of my life outside monogamy, I have arrived at an idea of this painting as a way to frame a new kind of intimacy that allows the possibilities of entropy that a life of emotional wandering requires.

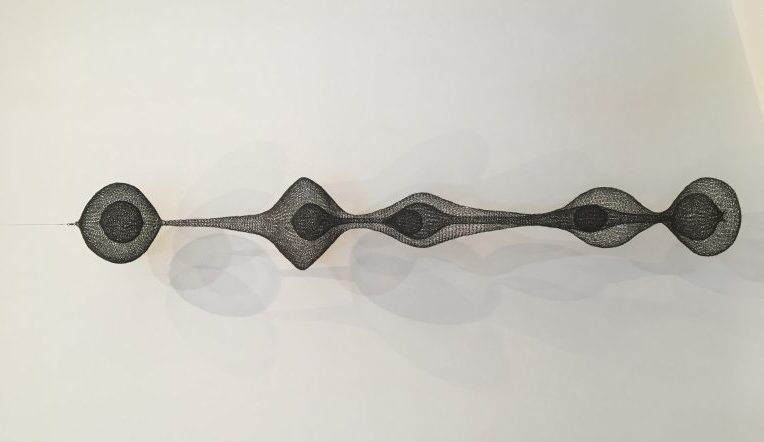

This type of intimacy isn’t solace. It isn’t exactly freedom either. It’s a kind of infinite loop that embodies the brilliance of the random and undefined. It looks something like the sinuous wire mesh forms the artist Ruth Asawa spent her life sculpting, drawing and piecing together in collages— continuous forms within forms that are at once intimate and hyper-aware of space and the ways that things often overlap and require shifting perspectives.