The Flâneuse: Walking in London and Paris

While Paris was never meant to be viewed from Google Earth, the builders of Notre-Dame certainly knew that the view from its highest towers provided the best glimpse of all that we consider Parisian. The bell tower of Notre-Dame is the one from The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, where Victor Hugo describes thirteenth-century Paris through the lens of the nineteenth century. In Hugo’s time, Notre-Dame wasn’t so well-maintained, and for the twenty-first-century reader visiting the cathedral, the novel asks the visitor to navigate three versions of the same city—the same sort of mental juggling we all experience when visiting a city for the first time.

Before climbing the tower, I watched part of a service given in the cathedral in Latin and French. The altar boy wielded a thurible of incense, leaving behind him an undulating cloud that transfigured the tourist trap into a medieval holy place. While exquisite, the high Gothic ceilings, stained glass, and mementos don’t compare to the outside of the building, where a thousand carvings proudly adorn the arch above its wooden doors.

After leaving the cathedral floor, I ascended at least four hundred steps before stepping, out of breath, onto the first balcony below the bell tower. It’s important that I climbed every stair, that I felt the lactic acid pooling in my legs. There are plenty of good views easily attainable in Paris that don’t ask patrons to climb hundreds of steps, but part of what makes me feel strong when I reach the summit is the effort. Part of what makes the view so satisfying is seeing exactly what I expect—the iconic gargoyles suffusing the cathedral with all the charm I remember from Hugo’s novel.

From the second balcony, there is an even better view of the city: the perching hill of Montmartre three miles away, crowned by Sacré-Cœur; the dome of the Pantheon to the south; the square next to Shakespeare and Company across from Notre-Dame. I can’t see from end to end of Île de la Cité, but I know even from here that it doesn’t have a definable shape beyond what was imposed by medieval stone walls and the erosion of time. André Breton identifies Île de la Cité, as Michael Sherringham phrases it, as “the body of a recumbent woman whose vagina is located in the place Dauphine.”

Even after closely examining the island on Google Maps and imagining the roads surrounding the square as a woman’s legs, Saint-Chapelle as her bellybutton, and Notre-Dame as the center of consciousness, I don’t see it. Even after spending seven days in the triangular Dauphine, I’m not convinced that the island looks like a person at all. And why does she have to be a woman?

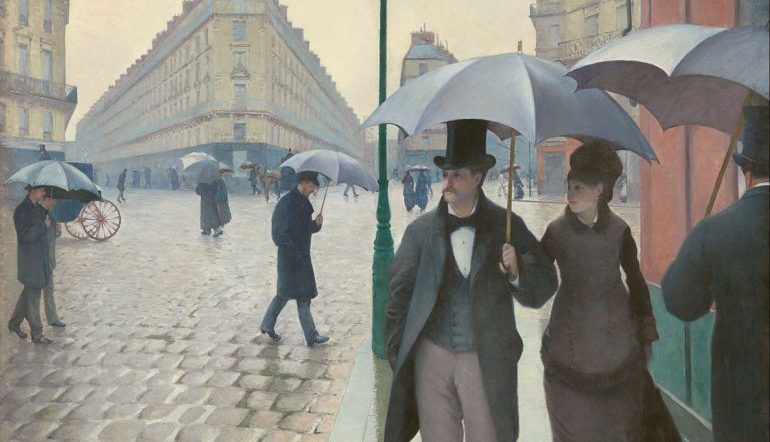

We speak of things like ships, cities, and even the earth itself as female, yet men are so often the ones confidently plodding through these spaces in literature (and in the corporeal world), conquering them as they would a female body. Even if we’ve progressed enough as a society to move past the laws that kept women in nineteenth-century Paris from safely walking the streets at night, meant to keep them indoors so as not to be confused with prostitutes, we still differentiate between the male and female streetwalker. We still tend to wonder if women can even wander Paris at night, if all cities aren’t just a little too dangerous for women to walk through alone. But women walk the streets even when the dialogue can’t catch up to them; I saw them on the Metro, their shoes often the first thing I noticed. From black heels to teal New Balance trainers, there were no assumptions I could make about the person wearing them except that she chose her footwear with purpose, for comfort or style. Walking in Paris is not an afterthought.

In Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London, Lauren Elkin defines the flâneuse as “an idler, a dawdling observer, usually found in cities”—a made-up definition because “most French dictionaries don’t even include the word” or, worse, define the term “as a kind of lounge chair.” It is derived from flâneur, a word that we associate with the male walker developed by Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Flâneur began, however, as a genderless word.

The first mention of flâneur occurred in 1585. At the time, it was defined, in genderless terms, as “a person who wanders.” Elkin suggests that the concept was not gendered until 1806 at the earliest. By 1854, however, Harper’s Magazine was clearly utilizing the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition, “a lounger or saunterer, an idle ‘man about town’”:

Did you ever fail to waste at least two hours of every sunshiny day, in the long-ago time when you played the flâneur, in the metropolitan city, with looking at shop-windows?

Harper’s use of the word suggests a degree of playfulness, an urban sprezzatura, that is distinctly male.

Some wonder if, by the time the word had taken on a gendered meaning, the flâneuse could have even existed, as both the social and legal structure of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries discouraged women from walking alone. Regardless of whether times have changed enough for us to accept the flâneuse in concept, she now makes herself at home in the pages of countless books, daring us with her ardor for city life.

I relate to her on a personal level, even if I am more tourist than flâneuse. Take the walking women of Paris that Elkin identifies, like George Sand, who found it easier to wear men’s clothing to walk the streets than face the ridicule and attention of a feminine skirt that made her a target. Or notice Jean Rhys’s lonely women from the novels like Good Morning, Midnight that reveal a tragic portrait of what happens when women are made vulnerable by the structure of a society that asks them to be angel or whore, teaching them that isolation is only good for the idle male walker with nothing but time. But, Virginia Woolf’s walking women stick with me the most.

A product of Victorian notions of walking, Woolf sought and celebrated a woman’s prerogative to walk the streets of London. In her essay “Street Haunting,” the narrator leaves home on an errand to obtain a pencil. We know in reading the essay that it’s not the errand that matters but the walking for walking’s sake. This essay is one of the most quoted examples of Woolf’s inherent passion for walking, the same that we see mirrored in her novels. Mrs. Dalloway’s Clarissa Dalloway, for example, is an iconic flâneuse, leaving a sizable imprint on our modern ideas of women walkers as different from male urban explorers who have far more freedom to roam.

Clarissa, early in the novel, leaves her home to obtain flowers for a party she’s attending later in the evening, demonstrating the same sort of enthusiasm Woolf has for walking. As Elkin explains, Woolf assigns Clarissa an “intense, embodied relationship to [the city’s] atmosphere,” which is supported by the early lines of the novel: “What a lark! What a plunge!” she thinks of the city, a sense of optimism pervading her actions. Immediately, we understand that Clarissa walks for the sake of walking, since obtaining flowers for a party is a sort of luxury—just as walking the city safely is also a luxury for many people who don’t feel safe in the streets. It’s this very desire to walk, even if it means coming up with a slightly insignificant excuse to leave the house, that defines the flâneuse in interesting ways.

Clarissa’s daughter, Elizabeth, also decides to strike out on her own in the streets of London. We see her waiting for a bus on Victoria Street, where she identifies herself as an “impetuous creature” and “a pirate” because she wanted to be free to explore the city on her own terms:

People were beginning to compare her to poplar trees, early dawn, hyacinths, fawns, running water, and garden lilies; and it made her life a burden to her, for she so much preferred being left alone to do what she liked in the country, but they would compare her to lilies, and she had to go to parties, and London was so dreary compared with being alone in the country with her father and the dogs.

In descriptions like these, we see the emotional resonances of Woolf’s women walkers. Although they are attuned to the liveliness of the streets, the focus always tends to turn to internal thought. With Woolf, internal life is one of the most propellant forces in her stories, giving us a window into the thoughts of the flâneuse as she explores the city.

Since I read several of Woolf’s novels before traveling to London, I noticed myself falling into these same internal, spiraling ideas. I don’t give myself credit for this but instead attribute it to the fact that Woolf understood the mind so well that she knew exactly where it might wander in the streets of London. Psychogeography may be the very reason that Woolf’s prose functions in such a way.

Guy Debord defines the term as “the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.” I initially discovered this concept on Tumblr and Pinterest, an odd discovery that made a metaphor of my exploratory habits on the internet—it was digital wandering that resulted in my decision to walk cities in real life, drawing me closer to the places literature had introduced me to.

Psychogeography is an important concept for both the flâneur and the flâneuse. Yet, the concept functions differently for a flâneuse than for a flâneur. For a flâneuse walking by herself, there is always the concern that her safety is at risk, that she will be challenged. It’s been the way of the world for so long now that we still haven’t shed the idea that women can’t walk by themselves, but, as in Paris, women walk the streets of London, proving that the flâneuse is not only possible but also thriving in a world that continues to challenge her existence. As Woolf conveys through her walking women, it’s important to experience such places for oneself, even when it seems like a risk.

In Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out, we meet Rachel Vinrace, a twenty-four-year-old with little worldly experience after a childhood spent in the countryside. One of the most telling elements of her character is that “she had scarcely walked through a poor street, and always under the escort of father, maid, or aunts.” Rachel enjoys the razor edge of privilege that enables her laziness, but, at the same time, she lives in a gilded cage that makes it impossible for her to be a flâneuse.

Although much of the novel takes place outside of London, the imprint of the city on characters’ memories makes it possible to consider the more rural walks of this novel through an urban lens, and, in a conversation with Clarissa Dalloway, who briefly appears in the novel, Rachel begins thinking about what it would be like to walk without a man in the city:

“I can quite imagine you walking alone,” said Clarissa; “and thinking—in a little world of your own. But how you will enjoy it— some day!”

“I shall enjoy walking with a man—is that what you mean?” said Rachel, regarding Mrs. Dalloway with her large enquiring eyes.

“I wasn’t thinking of a man particularly,” said Clarissa. “But you will.”

These moments that are interspersed throughout Woolf’s novels speak to the inequity between the flâneur and the flâneuse and to the implications of dismissing the female walker. But what may also be missed is Clarissa’s gentle encouragement to Rachel that there will be opportunities to walk alone in the future. While this, unfortunately, does not turn out to be the case for Rachel, Clarissa and Elizabeth embody the sentiment that the possibility of one day being able to walk freely is something worth hoping for.

This piece was originally published on July 15, 2018.