The Follow-Up: Josh Weil

I’m going to be talking to a few authors whose first books I admired and see what they’re working on in terms of a second book. One of the things that interests me here is how writers move from a shorter form to a longer one. Talking about the process while in the process is something I don’t see a lot, and I’m sure some writers would hesitate to do it. I have, however, found some brave souls willing to discuss their work, past and present.

Josh Weil was a friend of a friend, and, as fate would have it, he was the first person I met after arriving at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. I quickly came to know Josh as a great guy and a fascinating person, which I would explain, but it will become evident in the discussion below. Though I will say that I find most people who can grow a beard intimidating, and Josh took his beard running up mountains while living in a cabin he helped build. It’s almost too much. Adding to this fascination at the time I met him was the fact that Josh had sold a collection consisting of a trio of novellas, which seemed quite a feat considering the publishing climate and the general feeling about novellas (I would describe this feeling as numbness).

I read The New Valley and understood immediately why it had pushed through all the reservations people (especially editor-type people) would have. The writing felt vivid and contained those wonderful contrasts that all great writers have: sparse and yet lush, lean and yet full of life, fresh and yet familiar. Of all the young writers I know, Josh and The New Valley may have contained the most focused ambition; he has an innate sense of when to go for it that is difficult to describe. The book went on to win the 2010 Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction, and Josh was lauded as one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35” authors. All well deserved.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Josh about how The New Valley came to be and how the next book (or books) is coming along.

James Scott: What kind of initial resistance did you meet with The New Valley? Obviously a trio of novellas didn’t top the wish list of many publishers.

Josh Weil: What are you talking about? Resistance? I took my manuscript to the post office, and the postal workers threw glitter on my head and jangled bells and fed me fruitcake. You should have seen the parties publishers held for me just to lure me through the door.

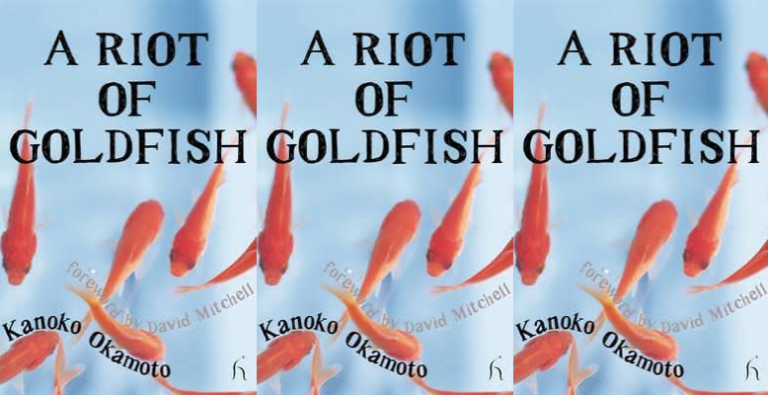

Um, yeah. No, there was definitely resistance, is resistance, to the idea of novellas. At least in the publishing world. That’s because there’s a lack of familiarity with the form among readers, so readers don’t know what to do with novellas, and publishers get scared about that, and then publishers don’t publish them, so readers don’t know what to make of the few that do hit shelves, and it all turns around and around on itself. That’s probably why my first agent was so unenthusiastic about my novellas (or maybe she just didn’t like them?). She read two of the three in The New Valley—didn’t want to do anything with one (the last in The New Valley), which she made clear by, um, hating it; the other (the first in my collection) she suggested that I try to turn into a novel. But she never seriously considered going out to editors with them.

JS: Well, that sounds like a real walk in the park. So then how did you circumnavigate that and find a receptive audience?

JW: My second agent. That is quite simply how. PJ Mark (who I’m still with, and to whom I’m still grateful) did more than consider going out with the novellas; it was his idea. I took him a pile of work—a novel, a collection of stories, and a second short novel –and he liked the short novel best. But he thought it was a bit too slight for my first book. At which point I admitted, while bracing for bad news, that it was originally a slightly shorter novella that was part of a collection of three. He was unfazed. In fact, he asked to see all three, read them over the weekend, came back on Monday saying, “This is what we’re going out with.” A collection of novellas by an unknown writer! Crazy. Except a week later there was interest from publishers. A few days after that it was sold. It all happened so smoothly and quickly you’d think the whole resistance to novellas thing was a figment of everyone’s imagination.

Which it both is and isn’t. It is hard to get readers to pick up novellas off a bookshelf (my publisher opted to leave any indicator of form off the front cover—so it’s just the titles, no “novellas” or “stories”) and it does place the book in a strange netherworld that doesn’t quite make it eligible for first novel prizes or for awards for short story collections. Also, reviewers are less likely to review it because they think readers are less likely to want to read it. Again, that vicious circle.

All that said, the relative rarity of novellas means that the book was something of a novelty. The New York Times did a full page review on it in part, I’m sure, because there was a uniqueness to a novella debut that there might not have been to a novel or a collection of stories. The novelty of it raised a few eyebrows, I think, and created an opening to talk about the form (and the book) in magazines and, well…here we are talking about it in an interview. And, happily, once there was some interest in the book, it seemed to do well as far as recognition and even with readers who I hope either discovered (or reaffirmed) their love for the form. That’s one of the things I’m happiest about: that the book, at least to a small extent, might have sparked a conversation about the novella, opened up readers and publishers, just a little more to the form. FSG (one of my favorite publishers) just published a beautiful hardcover of a novella by Denis Johnson (one of my favorite writers), which I just bought at Square Books in Oxford (one of my favorite bookstores) and am eager as all hell to read. Here’s the thing: the novella has been around (published in The Paris Review, I believe) for years and years, but only now came out as its own book. I’m sure that had just about zero to do with anything that happened with my book. But if, even for one passing second, the publisher thought Huh, well this debut author’s hardcover novella collection did OK, maybe primed the pump a little, and that nudged FSG even a smidgen towards the publication of a standalone novella, then, hell, I’d be happy. I do think the more that novellas are out there the more they’re going to be read—and loved. Because the form is ideal for right now, is something readers really gravitate towards once they know what it is.

JS: I definitely think that’s true. It’s hard as a reader to try something new, I think, because there’s already so much in the form you’re familiar with. And I started Train Dreams (the Denis Johnson novella) just the other night and am happy to report it’s amazing.

Was there a discrepancy between how your publisher thought the book would do and how it did? I think there’s a mantra in mainstream publishing that short stories don’t sell, and I imagine it’s worse for novellas. It’s kind of like the doom and gloom that pervades the industry, and yet a few articles recently have pointed out its health.

JW: You know, I’m not sure there was much of a discrepancy, but that’s partly because my editor/agent/publisher all were brave and kind of championed the novella form. Grove has published wonderful collections of novellas (from Jim Harrison’s many brilliant ones to Michael Knight’s wonderful The Holiday Season). So I think they knew what they were getting into. And they got behind it all the way. They were great. But also realistic: nobody expected the novellas to sell as well as a novel would have. And they didn’t. I mean, I was thrilled that they sold OK, but I think they sold just about as well as everyone who knew anything (i.e. not me) expected and hoped—and no better. They did garner some critical acclaim, but, as far as I can tell, that’s what story collections do: get noticed by people who love literature. Not necessarily bought by people who grab a book off the shelf for a summer read.

JS: So, the million-dollar question: What are you working on now?

JW: Three books at once! A novel, a story collection, and, yep, a novella collection. I know, I know: insane. But I’m hoping it will appear less so when they’re done.

JS: Thanks for making the rest of us appear so very lazy. How far into those projects are you?

JW: I’m just going to focus on the novel here because that’s the farthest along. And I hope it’s getting close. I’ve nearly finished what I hope will be the last major draft before it goes to an editor. But my agent may have something else to say about that. In which case I will punch him. Then admit he’s right and get back to work. And, honestly, I’ll probably only punch him on the shoulder. Very softly.

JS: I’m sure, then, that that punch will be very liberating.

The New Valley strongly associated itself with one place (on the border of the Virginias). Are you sticking around there or headed elsewhere? How does that feel?

JW: Oh, headed far, far afield. The new novel takes place entirely in northern Russia. Yup, you read that right. With Russian characters. In an alternative present. Yup, read that right, too. So, it’s very different from The New Valley in some ways, but I hope it still has a strong sense of place (I spent time in Russia as a kid, and recently returned to do research), and it’s really not that different when it comes down to it: the location changes, but my concerns, the interiors of the characters, the way my mind simply approaches scenes—I can still see the similarities between the new novel and The New Valley. Still, it is good to get out of Appalachia with my writing. Good because it allows me a new canvas to work on. But it’s not something I really chose: I wanted to write this story, and I saw this story as having to be in Russia, and then I wrote the first scene and realized it was something longer than a short story, and by then it had its hooks in me…and here I am writing a long, large, Russian novel. So, although I almost feel it chose me, I am glad it did. It’s a strange thing to be known (to the small extent that I am) as a writer based on just one book. I have loads of other, unpublished, earlier writing, of course, much of which is set outside of Appalachia. So it doesn’t feel like Appalachia is all I’m about as a writer—just that that’s the writing the outside world has seen so far (other than my short stories, which are mostly set outside of Appalachia). That said, I feel more strongly connected to Appalachia than anywhere, and it pulls on me more often, and I will write stuff set there again; I am eager, now, to return to it, to get home for a while.

JS: Is it more difficult for you to navigate the open spaces of a novel, or do you enjoy the room to stretch out?

JW: Both. I think they’re just different beasts—stories, novellas, novels—and the work is born whatever beast it needs to be. Then I have to deal with it. If I try to treat a mouse like a mountain lion I’m going to just look silly. And if I try to treat a mountain lion like a mouse things are going to get ugly fast. So, again, it doesn’t really feel like it’s up to me that much. I want to write a story. The story demands its own shape. Then I have to learn how to deal with that. And that’s great fun; I’m having a great time with it. Especially since, working on all three—the short stories, novellas, and the novel—at once has allowed me to shift things up. When I’ve just come out the end of a long wrestling with the novel, I’ll let it sit, go chase a mouse around for a while, or—like this past summer—take to the woods and run with the coyotes (by which I mean novellas in this increasingly ridiculous extended metaphor) before gearing up for a bout of novel/mountain lion wrestling again.

JS: That’s a lot of animals to be chasing. I know what you mean. It’s nice, sometimes, to have something to finish when you’re slaving away at something much larger.

How has the process differed this time around?

JW: The process, for me, is always different, every time around. Which is, frankly, infuriating. But it’s also, I think, necessary. I mean there are always some constants—just the way that I work, the routines to which I try to adhere, the way my mind gets at a story (for instance, I almost always am writing towards something as opposed to writers who start with something and see where it leads them; its just how story makes sense to me)—but each individual piece bucks off whatever expectations I have for it. Like I said, above, I thought this novel was going to be a short story. Started it as one. Then got through the first scene and realized it was going to be a very long short story. By the time I’d written 40 or so pages I knew I was facing at least a novella. And once I knew that, I could look back at what I had and see weaknesses that were going to collapse under the weight of the longer form. So I went back and filled those in, and then moved forward again, and again found that I was staring at not just a novella, but a short novel. Threads had appeared that felt important, but that weren’t threaded through well enough from the start. So, back I went again, threaded those through, moved on…and by the second draft I had come to grips with the fact that this wasn’t meant to be a short novel at all, but a long one. So I wrote about 450 entirely new pages, dramatically re-imagined the way I was telling the story, even aspects of the story itself. Now, if I tell you that the novellas, once I was underway with a first draft, pretty much rolled out the way I imagined them, you can see that that’s a pretty different way of working for me. But the form demanded it: a long novel is just too big to hold in one’s head, right from the start. Or at least it was for me. And my head didn’t even know what it was dealing with. Only the story, once I was deep into it, could tell me that.

JS: That’s a necessary component, isn’t it? Letting the story dictate itself. I use the term ‘story’ here meaning, I guess ‘work,’ not short story, but it really is the size and breadth of the story that figures itself out.

Do you think, for young writers, that shorter fictions are necessary training? Or can you leap right into longer work?

JW: Necessary? No. Less bruising? Yeah. I think a young writer can leap right into a novel. But she better be prepared to write one or two novels that go into the drawer and never come out before finally getting to one that’s working well enough. That’s pretty much how I did it (short fiction has been something I’ve come to post-novels). But, you know, it probably takes longer that way. I have five novel-length things—three of which I’d call novels—that were my training grounds. That’s probably not the most efficient way to learn. Hacking away at stories for a few years is probably more practical. But practicality has little to do with it in the end. You write what you’re driven to write. And you write in the form that speaks most powerfully to you. And if that’s novels or novellas instead of short stories, then I say go to it. And enjoy the hell out of every page that you can. Because there are going to be a lot of them.