The Greensboro Five

Guest post by Carol Keeley

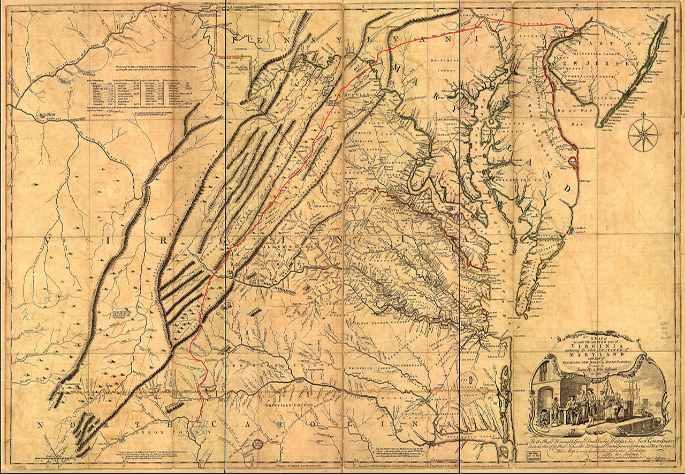

Among the iconic civil rights heroes in a recent Platon portfolio in The New Yorker were the Greensboro Four. The image of these young men at a whites-only counter in Woolworth’s ignited a movement and is part of our national conscience. But this shot includes a terrified young man who has too long gone unidentified.

Behind the counter is James Spencer Dungee. This photo, taken the second day of the sit-ins, includes only two of the actual Greensboro Four. Spencer was nineteen. He had worked at the store for five years and had advanced to working the grill. Though he knew two of the protesters from Dudley High School, he knew nothing about the planned sit-in. “I was more shocked than the managers,” he says today.

On February 1, 1960, four college freshmen sparked a revolution by waiting for Woolworth’s to open, then calmly sitting at the lunch counter. Blacks were expected to get food at the pick-up station and eat elsewhere. As they sat down, Spencer kept whispering, “What are you doing?” He knew the cost of such courage. His cousin, Josephine Ophelia Boyd, was the first black student at Greensboro Senior High School. While the Little Rock Nine, escorted by federal troops, was making national news, Spencer was organizing carloads of friends to patrol his cousin’s dangerous journey to and from school. While there, she endured students spitting in her food, splashing ink and ketchup, endless insults. At home, two family dogs were killed, death threats phoned; her mother was fired and her father’s sandwich shop incinerated. Spencer knew what quiet teenagers seeking justice suffered.

“Just be cool,” his friends whispered back to him. The Woolworth’s manager let the freshmen sit, without service, until closing the store early. He figured that would be the end of it. The next morning, they returned, joined by nearly thirty others. Within days, there were three hundred students at the Greensboro Woolworth’s, and protesters occupied lunch counters in fifty-four cities across the South. “That’s when I got scared,” Spencer says. “I was more afraid of somebody getting hurt, you know, someone losing his temper. That’s when you had to think about it.” Police started arresting protesters mid-week, as downtown businesses were impacted. Sit-ins spread to Walgreen’s and other five-and-dimes, Spencer recalls, but not to Kress, a department store that complained of bomb threats. “Their food wasn’t worth it,” he chuckles. “Hot dogs for ten cents, you know. And they tasted like ten-cent hot dogs.”

The first day was uncomfortable, but one manager seemed “understanding of the situation,” Spencer says carefully. That night, he sought out one of the organizers, Ezell Blair–now Jibreel Khazan–whose father was Spencer’s eighth-grade teacher and a close friend of his mother’s. “It is what it is,” Mr. Blair told him. “Something’s got to happen. You just got to bear with it.” So Spencer went to work every day. They’d shut down the counter service; instead of working the grill, he was mopping floors, working the stock room. The managers kept asking, “How long has this been planned?” It wasn’t clear they ever believed he had nothing to do with it, Spencer says. Some of his coworkers and their families seemed less antagonistic. “These people weren’t strangers to me,” he stresses. But asked if he felt supported, there’s a long silence. “Well, you know,” he says, with a tolerant smile. “It’s like Mr. Blair said, ‘It is what it is.’ It had to be done. We just didn’t know what would come of it.” He is proud that there was no violence and believes this is “because it was organized by some very intelligent young men.”

Spencer wasn’t fired from Woolworth’s, but “you could feel the animosity. You know, like instead of working the grill, I was doing more janitorial, getting the night shifts.” News coverage helped to spread the movement. But it also wounded. After this photo flashed nationwide, Spencer was turned down for jobs all over Greensboro. Two of the Four who stayed in town were labeled troublemakers and forced to leave. Spencer felt the same pressure. Out of fear and frustration, and desperate to make a living, he moved north, where he has lived since. “I drove to New York on July 14, 1962,” he says, “and started working July 20.”

His work ethic is as keen as his memory. Forty-two years with the same company; never missed a day of work driving an 18-wheeler in the tri-state area. He gets checks from Allstate every year for good driving, he beams. Friends and family would rather ride with him than fly. He recently drove an 89-year-old relative back to Greensboro for a funeral. “You sure you can handle the drive?” Spencer asked as he helped the frail man into the car. “Handle the drive? Can I handle the drive?” his cousin mocked. “Question is, can your car handle me?” Now retired, Spencer rises each day around four a.m. to plan the day’s errands. “Spencer, you flunked retirement,” his friends tease him. His family still has land in Greensboro, a legacy from his great great grandfather, who purchased sixty-seven acres in 1864, as the Civil War was raging. Presumably he passed for white.

Recently

called for jury duty on a case involving nightclub violence, Spencer was bounced during vois dire. It wasn’t because he had family who’d survived similar violence, which he never mentioned. It was because he’d insisted, “I don’t know what happened. I wasn’t there.” There’s purity in that statement, but also poignancy. His America still requires vigilance. Or maybe he lives by the animating principle of the non-violence movement, satyagraha, which translates roughly as “truth force.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. agreed with Gandhi that satyagraha “is the weapon of the strong; it admits of no violence.” The force of truth requires no sidearms or militia. “One who is free from hatred,” wrote Gandhi, “requires no sword.”

The photo of the Greensboro Four vibrates still. It’s living history. The Woolworth’s building in Greensboro is now the International Civil Rights Center & Museum, where the counter remains. Spencer Dungee paid a steep price for this pivotal moment. Perhaps the caption here should be the Greensboro Five. While these noble civil rights veterans are rightly celebrated in our still complicated times, Spencer reminds us that there were many unnamed soldiers quietly bearing the cross and braving change, helping to cleanse a blood-stained nation.

Footnote: In an oral transcript, Charles O. Bess appears to identify himself in the aforementioned photograph. There’s no corroboration of this on record. The International Civil Rights Center & Museum has not identified the man in the photo. A spokeswoman said several men have casually made the claim, but no one has pursued or provided verification. I base my claims on visual inspection, plus interviews with numerous Greensboro residents who knew Spencer then, identify the image as his, and confirm the consequences of his visibility. I welcome any research that confirms or denies these assertions.

Greensboro photo from The Root. Dungee photo by Johannes Weidenmuller.

This is Carol’s second post for Get Behind the Plough.