The Humanity of True Crime’s Victims

When it comes to true crime writing, the more shocking elements of the story often, inevitably, become the focus of the narrative. Even the best-meaning writer can fall into the trap of focusing on the perpetrator and their actions, leaving victims, lost to death, remembered more for how they died than how they lived. Maintaining a balance between sharing stories that are undeniably fascinating and illustrating the humanity of victims, and their loved ones, at the center of tragedies is difficult to navigate.

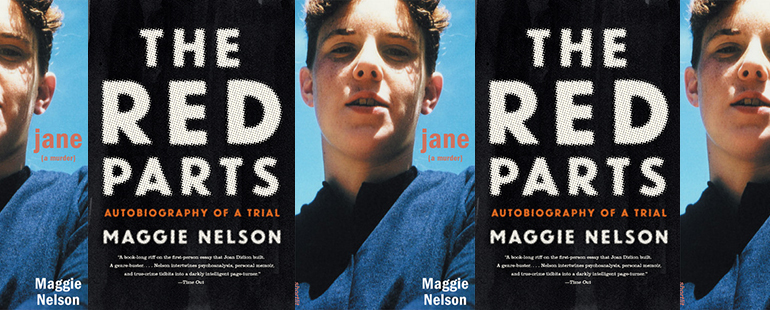

In two books, Maggie Nelson manages to recount the murder of her aunt, Jane, in terms that don’t elide the true horror of the situation, while keeping Jane’s voice firmly centered for readers. She accomplishes this through the use of Jane’s own words, taken from her diary and letters, in her book of poetry, Jane: A Murder, from 2005. (While Nelson picks fragments from Jane’s writings and arranges them to suit her poetry, these quotes are always clearly marked in the text.) Because Nelson uses Jane’s words—and, thus, her thoughts—to supplement description of the events of the eventual crime, readers are exposed to who Jane was beyond who she became in the aftermath of the murder. Nelson focuses on who Jane was in life—a smart, vibrant, and politically active young woman studying law at the University of Michigan in the late 1960s—rather than portraying her as a nameless third victim in a series of murders that took place in Michigan.

Jane opens with an excerpt from Jane’s diary, discussing both the purpose of her journaling and the reason behind Nelson’s eventual turn to her family history:

Dear

I understand many people write for therapy—one’s own.

So this epistle, addressed to no one,

is therapy for me. What have I got to say—

oh a lot of crazy impressions about nothing

I imagine

The collection was written, in part, as a way to heal Jane’s family, and to help Nelson understand the impact that Jane’s murder had on her relatives. In her 2007 memoir The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial, Nelson admits that she never believed that Jane’s murder would be solved, that she thought she and the rest of the family would live with an unanswered question for the rest of their lives. Nelson writes, “I had been given an endpoint: the publication date of Jane, on my thirty-second birthday, in March 2005. As soon as I held the book in my hand, I would be released. I would move on to projects that had nothing to do with murder. I would never look back.” The process of researching and writing Jane, then, was intended to be both a labor of love and a way to expunge the demons that circulated within her family.

Yet, as The Red Parts unfolds, it becomes clear that even if Jane’s murder had remained a cold case, the effects of the event would live on through what Nelson calls “an inheritance”—an inherited fear that was passed on not through explicit conversation, but through the nonverbal ways human bodies try to assimilate trauma and pain. Nelson’s mother realizes as she experiences the process of the trial that Jane’s death, though occurring thirty-five years earlier than the events in The Red Parts, did in fact have a lingering effect on her and how she raised her own two daughters. Nelson writes, “[my mother] dreams of an impermeable, self-sufficient body, one not subject to uncontrollable needs or desires, be they its own or those of others. She dreams of a body that cannot be injured, violated, or sickened unless it chooses to be.”

Like her treatment of Jane, Nelson is intentional in The Red Parts about humanizing the people experiencing the trial. Though the memoir provides information that is more in keeping with the standard true crime book, including graphic explanations of the crime scene photos both Nelson and her mother bear witness to, Nelson always grounds the experience in the affective response she has to these images and uses her emotions as a way to think through larger questions of cruelty and justice. Though the murder becomes more of a focus in The Red Parts than it was in Jane, Nelson is careful about assuming she has concrete answers to what justice is. She recounts how the detective in charge of Jane’s cold case, Schroeder, tells her about how Jane’s ghost would appear to him, urging him to press on with the investigation. But Nelson isn’t interested in speaking for Jane in this way: “I’m still not sure, however, who Schroeder’s Jane is, or who my Jane is, or what, if anything, they have to do with each other. Whoever or whatever they are, I can’t imagine they bear much resemblance to Jane, herself, at all.”

Out of those involved in the trial, including other family members, Nelson seemingly has the strongest claim to “knowing” her aunt. While The Red Parts is mostly about the trial, it also delves deeper into the research Nelson did to write Jane, and the emotional work that went into crafting poetry around this topic. Nelson’s research was so thorough that detectives read Jane and highlighted certain passages during their investigation, asking her how she came across each bit of evidence and crosschecking it against the information they obtained. Nelson’s unexpected role in the investigation, alone, would make for a great run-of-the-mill crime thriller.

The truth is, however, that few of us who come across true crime stories will have any link to those involved. Because of this distance, much of the media surrounding those narratives often falls into psychologizing from both sides—imagining the motivations of the perpetrators or guessing what the victim felt as the crime occurred. Though Nelson spent so much time researching her aunt’s life and death, she realizes that she might always be focusing on things that are, ultimately, unimportant. The things she fixates on, like conflicting police reports of the color of Jane’s rain jacket, seem significant, like something Nelson should know. Yet, after hours of research, she realizes that the “truth” is lost to history—and that this detail about her aunt reveals so little about her in the grand scheme of things. Rather than attempting to create a complete picture of who her aunt was, Nelson presents as much as she can, acknowledging the limits of her own understanding. Instead of fitting Jane into easily understandable categories, she allows the image of her aunt to be more unclear. The Jane presented through her diary and correspondence in Jane pushed back against being defined by external factors in life, so Nelson is careful to do the same for her in death.

Without the level of research and care Nelson takes in working with the genre, it can be easy to focus solely on the morbidly fascinating elements of true crime—there is something undeniably gripping about these stories, which can resonate in multiple ways. As Kate Tuttle noted in the New York Times earlier this summer: “My fascination springs from the same sources that have always drawn people to the genre: straightforward curiosity, vicarious thrills and a kind of magical thinking that maybe if you consume crime as art you’ll never confront it in real life.” There are complicated reasons for why many consume true crime media, as Tuttle’s piece points out. But in an essay on the murder of a beloved cousin, “Don’t Use My Family For Your True Crime Stories,” Lilly Dancyger argues for a more reflexive approach, such as that taken by Nelson, to these stories, regardless of how morbidly fascinating they may be. She writes:

I don’t begrudge true crime fans their shows. I’m not here to tell you you’re a bad person if you enjoy these stories. But I wish that the audiences and creators of these shows would give a little extra thought to how the dead woman (because it’s almost always a woman) at the heart of the story is treated in the telling. Is she treated like a human being who had more life left to live, with people who loved her, who will never be the same because of her loss? Or is she reduced to a gory crime scene photo and a plot point in a story about a man who doesn’t deserve anyone’s fascination?

Like Nelson’s Jane, Dancyger focuses a significant portion of the essay on who her cousin was in life, centering the story on how much good was lost when she was murdered. Dancyger thus presents another example of the raw, personal impact implicit in true crime stories. The tendency of true crime reportage is to focus on the act of the perpetrator: how many they harmed, how long their spree was, whether there were signs in their childhood pointing toward these later crimes, and so on. As consumers seek out more material, more of these stories might be told for the general population. For Dancyger, though, the thought of her cousin’s death being used for entertainment, no matter how educational it purports to be, is deeply devastating.

Both Dancyger and Nelson argue for humanizing victims and keeping them, and their loved ones, at the center of true crime stories. Nelson refuses to believe she knows what Jane would have wanted and what justice truly looks like in this setting; as such, reading Jane and The Red Parts in tandem provides an example of how to treat these stories, and most importantly, their victims, with care. Nelson’s nuanced approach works so well, in part, because of her undeniable skills with language. But, more importantly, she provides an example of how to write about true crime through her treatment of all parties involved: first and foremost, as human beings.