The Impossible Citizen in Jill Magi’s SPEECH

Abu Dhabi-based poet and artist Jill Magi creates the “impossible citizen” in her latest poetry book, SPEECH. Her narrator is an investigator and an admirer of the world, who moves between unnamed lands in places that might be Middle America and might be the Middle East, pushing past class, national, and temporal boundaries. As a result, Magi revives a cosmopolitan way of being that has gone out of favor in the United States and elsewhere. In this book-length poem, textures of physical borders are examined as speech while actual speeches are recovered from books and archives to reveal ways we might begin to comprehend the borders that entrap us.

In the United States, our notion of cosmopolitanism has become fraught. At present, the word is misconstrued to mean self-celebrating urban elites who feel comfortable traveling in homogenized global spaces. This version of a cosmopolitan, like the globalist, cares little for their home country and disdains those whose education, religion, and politics are unlike their own. Their conversations may circle high-brow topics, but their speech becomes banal, passive, and yearns for uncomplicated consensus. These kinds of people may exist, certainly, but they are not Magi’s ideal world citizen. Her work instead calls to mind the writings of philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, who argues for a “partial cosmopolitanism” in the form of a person who naturally shows preference for those closest to them (family, neighbors, fellow citizens), and yet who also recognizes their “obligations to others” and takes “interest in the practices and beliefs that lend [other human lives] significance.” Appiah’s partial cosmopolitan believes “there is much to learn from difference” while conceding that “universal concern and respect for legitimist difference [can] clash.”

Magi’s impossible citizen experiences both that joy of difference and the breakdown of speech during clashes. For example, when her impossible citizen is browsing at an antiques souq, she is not allowed to buy a holy book. She says, “Because of the wrong religion I was allowed to see the writing inside and not to touch.” When the impossible citizen asks why, the bookseller says, “we are a tolerant people.” The exchange is profound because each side feels like they are doing the right thing, that they are opening up to someone of difference, but speech has led to an impasse. Does it qualify as a clash? How can we know the difference between respecting difference and condoning maltreatment? James Baldwin offered an effective barometer when he wrote, “We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.”

The opening line of SPEECH reads, “She went out for bread”—a charming evocation of Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” SPEECH and Mrs. Dalloway share structure, themes, and creative uses of time. Both texts are like one long walk through a physical place, but also through history. Their narrators wend their way through their cities while being hyper self-conscious and willing to merge with whatever or whomever they encounter. Magi’s nod to this Bloomsbury gives readers a sense of the seriousness of her political intention with this work. SPEECH asserts itself within a literary tradition that is radical in its critique of inequity, discrimination, and traditional ideas of how to organize society.

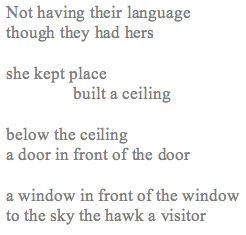

At the same time, like Magi’s impossible citizen, the Bloomsberries were a privileged bunch. Several times, Magi acknowledges her narrator’s burden of privilege: “opening and stirring / her suitcase of privilege while she / over distance spoke.” This line suggests that privilege, once recognized, becomes something that one must continually reckon with, but that the distance ought not to deter speech between unlike peoples. For example, while Magi’s narrator is out for bread, she watches a man mopping an auditorium floor “used for bridal gowns, gun, and political conventions.” Whether this is Chicago or Abu Dhabi, one can assume this manual laborer’s life has different restrictions and joys than our narrator’s. Eventually, a uniformed guard closes the door to the auditorium and narrator is left outside. Was the guard told to close the door? Did he want to close the door? Later, she listens anyway through the door as a famous leader speaks. It is easy to visualize the impossible citizen here. She is curious. She only gets snippets of the speech, which Magi indicates by large spaces between the words, like Mad Libs. This implies that all speech is part-silence and part-creation too. There’s something collaborative about it.

Magi’s impossible citizen is also the title of Neha Vora’s excellent book on Indian communities. At the start of different sections of the poem, Magi archives speeches by celebrated voices like Vora, as well as Fred Moten and Arundhati Roy, etc. In “Painting a bibliography.”, Magi nudges us towards these voices by reminding us that a book’s structure “can be subverted by reader sovereignty at any time.” Thus, we can begin the journey of SPEECH through the words of Vora, Moten, Roy, etc., instead of the shadow of Mrs. Dalloway. For example, Moten’s speech: “So I want to argue, or move in preparation of an argument, for the necessity of a social (meta)physics that violates individuation.” We can then read the impossible citizen’s journey through borders from Moten’s point of view. There’s something remarkable about this structure. It is more powerful than epigram. Magi has developed a way to voluntarily give space for other voices (often marginalized voices) within her own work and speech.

More than anything, SPEECH becomes a collaged discourse on class and individual protectionism. In one of her sections that excerpts famous speeches, Magi reminds us of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s oft-buried rhetoric on economic justice. In beautifully layered sections, Magi juxtaposes world events with her narrator’s individual actions: “and as King’s visit to India solidified his anger at poverty and imperialism, / she pushed the button to start the treadmill.” In SPEECH, it’s a fact, not a condemnation, that we all live simultaneously. Because of this, we also take measures to protect ourselves, measures that can sometimes be further border-making:

SPEECH addresses many types of physical borders from checkpoints to “a blocked window” to “walls dividing those who mostly worked with their hands from those who mostly worked at desks.” Magi describes these walls as “concrete and thick like stone that might skirt an old city” and in doing so, we are asked to consider labor’s ancient and enduring divide (the principle subject of Magi’s 2014 book LABOR). Stone walls evoke images of feudal society and the medieval castles of Europe and shogunate Japan, a time when wealth was in the hands of a few. We like to think society has escaped feudal forms of political organization. So why are these stone walls proliferating? What do these borders say? In his book What Unions No Longer Do, Jake Rosenfeld details the decline of labor unions in industrialized countries, a trend that is more severe in the United States (“the private sector in this country is now nearly union-free”). Rosenfeld says, “The historical pattern is clear; the cross-national pattern is clear: high inequality goes hand-in-hand with weak labor movements and vice-versa.” In the UAE, another possible setting of SPEECH, trade unions and worker strikes are illegal. We are left to consider how divisions of labor entrap us. Also, who is speaking out about this? Whose speech includes and excludes mention of labor movements?

Magi’s “impossible citizen” dreams of “a guaranteed income” and even lays invectives against us for our mishandling of our environment: “please put away your / moralism phones / and make / your own paper.” She also questions parenting: “I mean to say that most / do not believe in equal / and will advocate for less / versus their progeny more—”. While Appiah would agree that it is okay to be partial to our own children, there must be a way that good parenting and good citizenship can happen simultaneously. Consider the borders of college admissions. When parents advocate for Affirmative Action, they want to redress past inequity. Research shows the outcome of AA is that beneficiaries enhance the learning community for all students and ultimately become better citizens. On the other hand, parents who advocate for legacy admissions (a practice that has expanded in recent years) do the opposite of addressing past inequity. There are extreme cases, too, like we saw in 2019’s Hollywood admissions scandal.

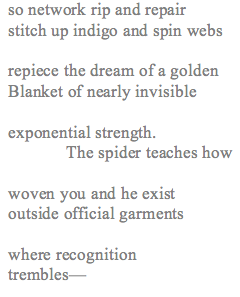

In the best instances, these borders are porous, loose, and can be manipulated into new identities with novel frameworks. In one declaration, Magi writes:

It is unsurprising to learn that Magi is also a weaver, knitter, and sewer. You feel this quality in the way her impossible citizen walks—or, better yet, weaves—through the city, pulling its various histories and injuries into this text. A true cosmopolitan may, perhaps, be a loom. Maybe Magi’s impossible citizen isn’t not possible, but rather, her ways are unrecognized. Her manner is to create.

This piece was originally published on February 4, 2020.