The Joy of a Disabled Life

If, on the day of its publication, an author was told their book would still be relevant, perhaps even more so, in 30 years, they would likely be thrilled. I imagine Nancy Mairs, however, would let out a long, knowing sigh, one that says she’s not surprised, but she’s still disappointed.

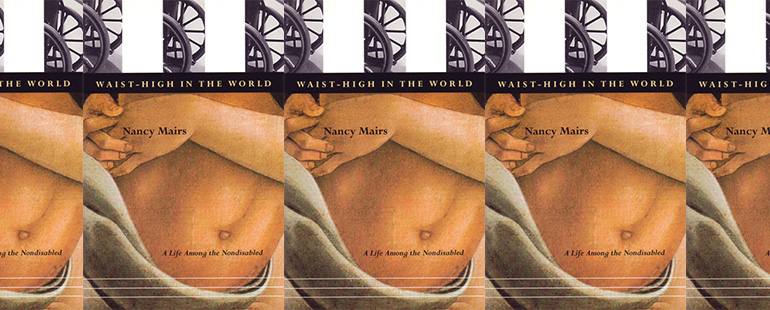

Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in the 1960s, by the time Mairs published her essay collection Waist-High in the World: A Life Among the Nondisabled in 1996, the white matter of her brain had been “shot to hell,” and she primarily used a mobility aid—a Quickie P100 electric wheelchair—to move through the world. Throughout the book, Mairs has a clear, singular intention: to demonstrate to “readers . . . who need, for a tangle of reasons, to be told that a life commonly held to be insufferable can be full and funny. I’m living the life. I can tell them.” Such a concept was, and unfortunately still very much is, a radical one.

I count myself among those readers who needed Mairs’s voice. When I was first diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, I collapsed under a heavy wave of dread—an overwhelming sense that my life would be more complicated and thereby less joyful because of my disability. I know, however, that I’m not the only reader whom Mairs foresaw approaching her work from this perspective. In fact, she appears to have written these essays specifically with readers like me in mind, with the goal of creating a travel guide of sorts for living with a disability, an altruistic attempt to “make the terrain seem less alien, less perilous, and far more amusing than the myths and legends about it would suggest.” A quarter-century later, we are, in some ways, in need of Mairs’s words now more than ever.

In the midst of a global pandemic, what disability advocates are calling, after Imani Barbarin, a “mass disabling event,” there are some who would seek to strip disabled Americans of the few legal protections we have. This past fall, CVS Pharmacy was prepared to go to the Supreme Court to argue that so long as discrimination against the disabled was “unintentional,” it was not in violation of any law. Only after public outcry did CVS dismiss the case and release a joint statement with disability groups, committing to “affordable and equitable access to health care.”

The premise of this case is disturbing. Whether CVS was aware of it or not, the fact of the matter is that most discrimination against the disabled isn’t “intentional.” It is most often the result of thoughtlessness or neglect; but this doesn’t make the discrimination (or, to use legalese, “disparate impact”) any less harmful. In fact, this sort of negligence functions as an effective erasure of the disabled. If accommodations aren’t provided, if our environments aren’t structured in a way that allows for the disabled to fully participate in society, then we are behaving as if disabled people don’t exist. And as Nancy Mairs baldly states, “whatever goes unseen goes unchanged.”

In Waist-High, Mairs dedicates some pages to specifically unpacking the connection between accessibility and erasure, addressing the issue head-on in the essay “Opening Doors, Unlocking Hearts.” Before plunging into the details, such as how private residences aren’t constructed with door frames wide enough for a wheelchair or showers with grab bars, or how public spaces typically only meet these types of requirements under the threat of litigation, Mairs opens the essay with the sharpest of deductions: “The world as it is currently constructed does not especially want—and plainly does not need—me in it . . . I mean simply that much of the time, as a disabled woman, I find that my physical and social environments send the message that my presence is not unequivocally either welcome or vital.” She then goes further, reaching beyond the fact that we live in a world that’s hostile toward disabled people into the heart of the matter: Why is our world built this way in the first place? The answer: Disability is the nondisableds’ worst nightmare, and they assume it must be ours, too.

Nondisabled people’s fear of disability most often takes the form of pity, which manifests in one of two ways: avoidance or feigned adoration. Mairs addresses both of these reactions over and over again throughout the collection. While it’s rather obvious that those who practice, in Mairs’s words, “studied inattention” when interacting with a disabled person are made uncomfortable by the presence of disability, some may ask how the expression of (again, in Mairs’s words) “unmerited admiration” is a display of pity. Mairs breaks this concept down better than I could ever hope to:

‘You’re so brave,’ they gush, generally when I have done nothing more awesome than roll up to the dairy case and select a carton of vanilla yogurt. ‘I could never do what you do!’ Of course they could—and likely would—do exactly what I do, maybe do it better, but the very thought of ever being like me so horrifies them that they can’t permit themselves to put themselves on my wheels even for an instant. Admiration, masking a queasy pity and fear, serves as a distancing mechanism, in other words.

From this deep, Mairs plunges deeper still. How does this fear, whether it’s manifested through avoidance or fawning, work to keep our world inequitable? According to Mairs, “the people who seem most hostile to my presence are those most fearful of my fate. And since their fear keeps them emotionally distant from me, they are the ones least likely to learn that my life isn’t half so dismal as they assume.”

On some level, nondisabled people recognize that they are one car accident or diagnosis away from being just like us–and that terrifies them. They believe that we must be in so much pain and suffering at all times, that it must be so thoroughly awful to inhabit our bodies, that our lives are not worth living. What most nondisabled people have yet to untangle, however, is that the source of much, if not most, of the pain and discomfort disabled people face is the hostile structures of our society: the public health policies, the physically inaccessible spaces, the ableism—not our disabilities themselves. If these issues were remedied, if disabled people were not only welcomed but cherished by our society, for something other than their capacity to “inspire,” there would be no reason to fear becoming disabled.

As Mairs wades through these issues throughout her book, she deploys a sense of humor that keeps the reader laughing, even as they confront such serious topics as eugenics and medical fraud. Some might assume that Mairs employs a dark humor, trying to make us laugh so we don’t cry. In one passage, for example, she writes, “The other day, when my husband opened a closet door, I glimpsed myself in the mirror recently installed there. ‘Eek,’ I squealed, ‘a cripple!’ I was laughing, but as is usually the case, my humor betrayed a deeper, darker reaction.” Immediately afterward, Mairs presents an analysis of how our culture portrays “illness and deformity” as “the consequence of cosmic bad luck” and “deviations from the fully human condition, brought on by personal failing or divine judgment,” resulting in Mairs being “appalled by [her] own appearance.” I’d argue, however, that this excerpt is an exception rather than the rule and, on the whole, Mairs’s commentary and asides are simply intended as humor. In one essay, Mairs discusses traveling while disabled: “Now that I can no longer dress myself,” she writes, “traveling alone to any destination other than a nudist colony is impractical.” In another, Mairs shuns the term “mobility impaired” with a quip: “Certainly I am not mobility impaired; in fact, in my Quickie P100 with two twelve-volt batteries, I can shop till you drop at any mall you designate. I promise.” Perhaps my favorite comedic aside of the whole collection is when Mairs discusses how her sex life has evolved, considering both her MS and her husband’s impotence. She writes, “And since my wheelchair places me at the height of [my husband’s] penis (though Cock-High in the World struck me as too indecorous a book title) I may nuzzle it in return.” Let me tell you: I cackled.

You’ll notice that many of Mairs’s humorous comments point the reader back to her disability, but she is neither making us “laugh so we don’t cry,” nor is she being self-deprecating in an attempt to beat others to the punch. Instead, Mairs calls our attention, over and over again, to the innate humor to be found in disability, which, just like any other aspect of life, has its inherent moments of levity. Through this use of humor, Mairs challenges her nondisabled readers to push past any discomfort or pity they might have once felt and instead acknowledge the fact that a disabled life is very much worth living; it is full of laughter and joy, and not even in spite of one’s disability—often because of it.

Although we won’t know the full extent of long-COVID’s impact for some time, we can almost guarantee that thousands, if not millions, of individuals will newly identify as disabled in the coming years. And although Mairs is writing in 1996, when COVID-19 was only sci-fi fodder, she points out that through advances in medicine and technology, people are living longer, which statistically increases one’s chance of developing an illness or being involved in an accident that will “permanently alter physical capacities.” With an eerily prophetic tone, Mairs concludes that “something without precedent is taking place, and we need a theoretical and imaginative framework for evaluating and managing the repercussions.”

If we don’t restructure our environments and our understanding of disability, accessibility, and equity, we risk making the world worse for ourselves and the people we love, no matter our disability status. It’s past time we all do the work to root out the ableism we’ve internalized. Even though—or because—we have MS or Crohn’s or asthma or astigmatism, as Mairs says, “our lives are too precious and delightful to us as they are.”